No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

A Full Guide to The Jib Sail And How To Use It

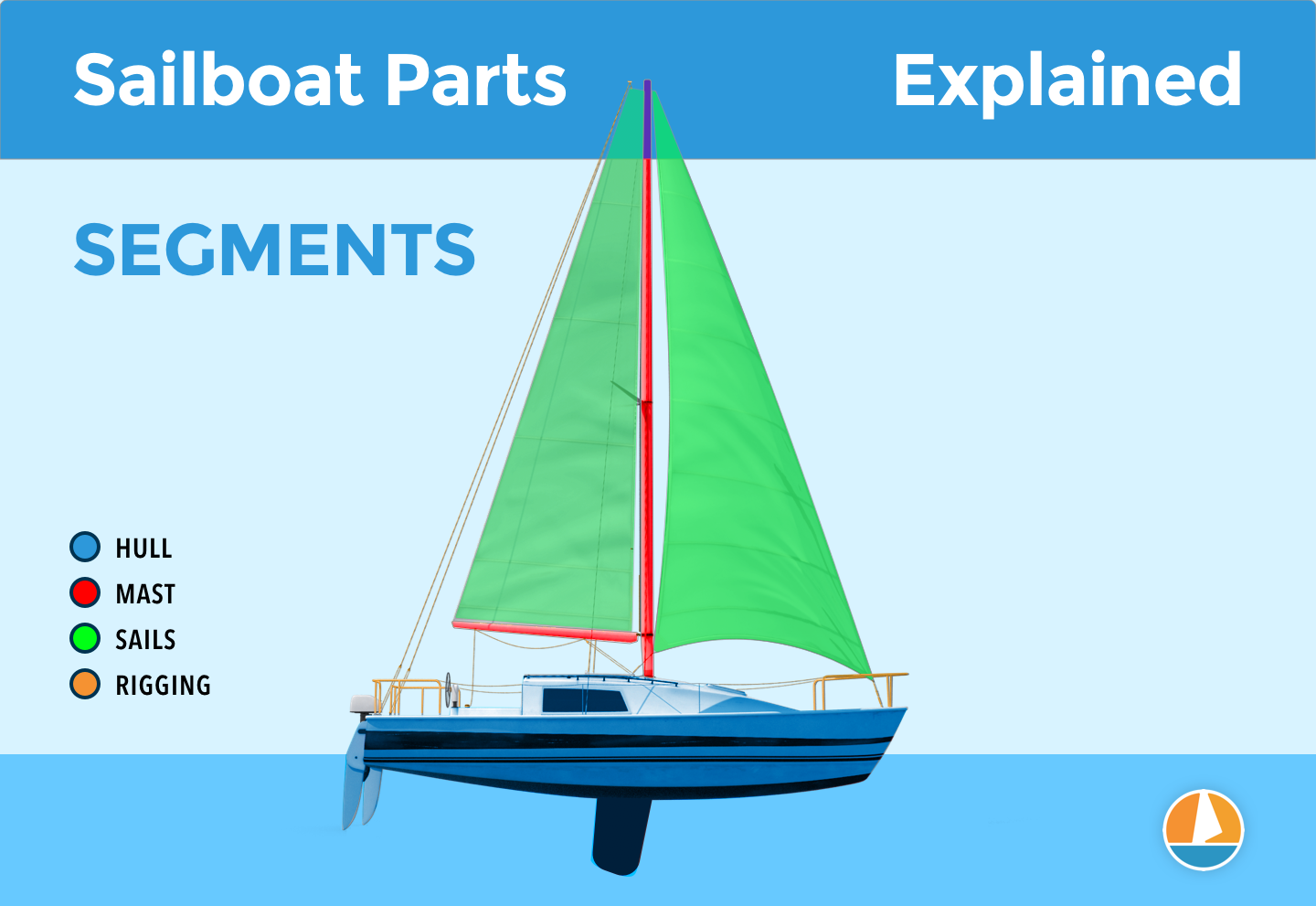

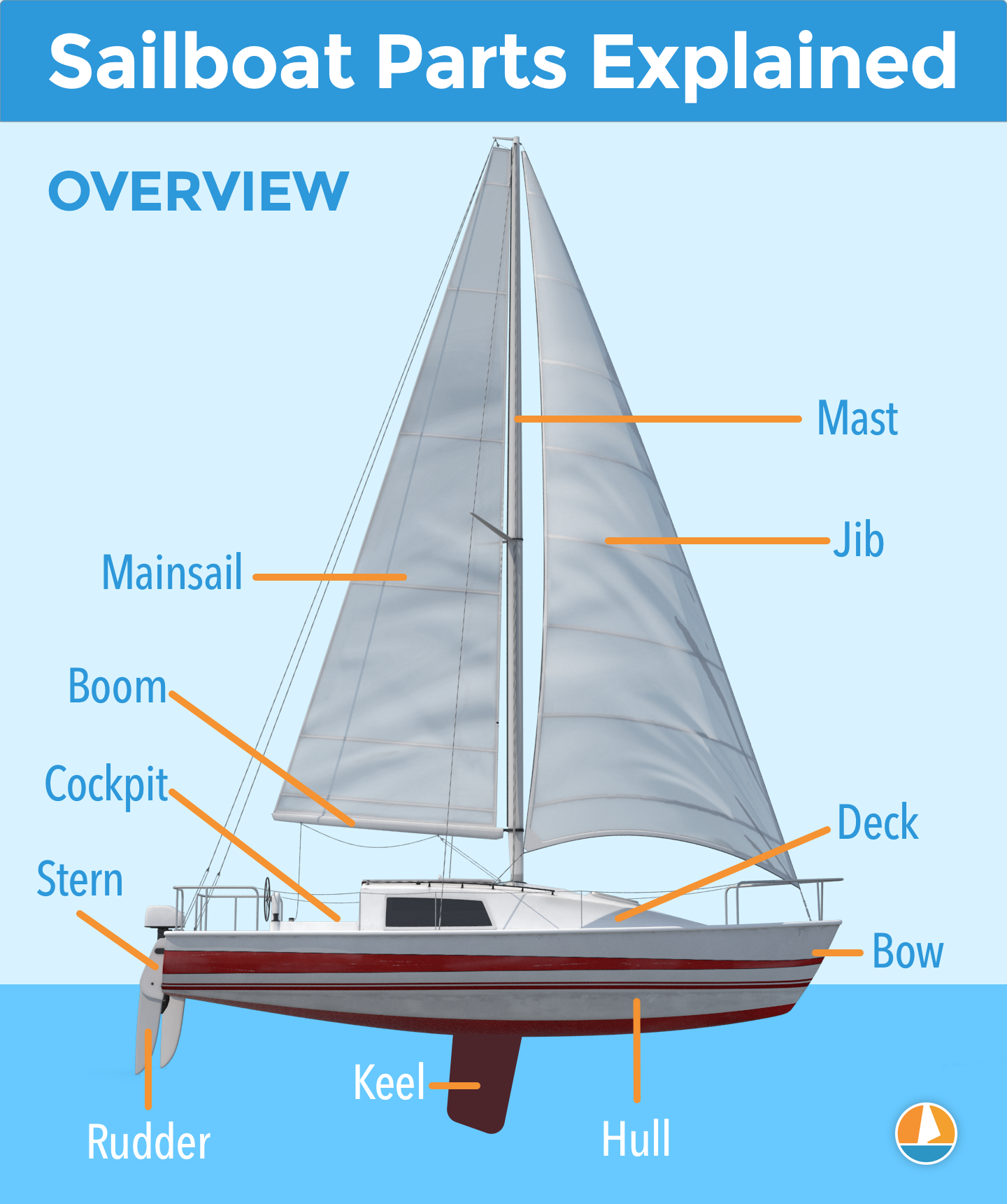

Most cruising boats today have a sail plan consisting of at least three sails: A mainsail, a headsail, and a light-wind sail.

The Jib sail (along with its sister, the Genoa) is one of the most widely used headsails on modern sailboats in combination with a larger mainsail. It is very versatile and easy to use in different configurations throughout most weather conditions.

In this article, I want to explain the Jib in detail and talk a bit about how it works and how we rig and trim it to get the most performance out of the boat. I’ll also show you each part of the sail and its materials before explaining how it differs from other headsails like the Genoa .

Finally, I’ll finish with some tips on maintaining the sail properly to make sure it last as long as possible.

Well, shall we get started?

What is a Jib sail, and what do we use it for?

The Jib is a triangular sail that does not overlap the mainsail. It is typically between 100% and 115% of the foretriangle size and is commonly seen on modern vessels with fractional rigs.

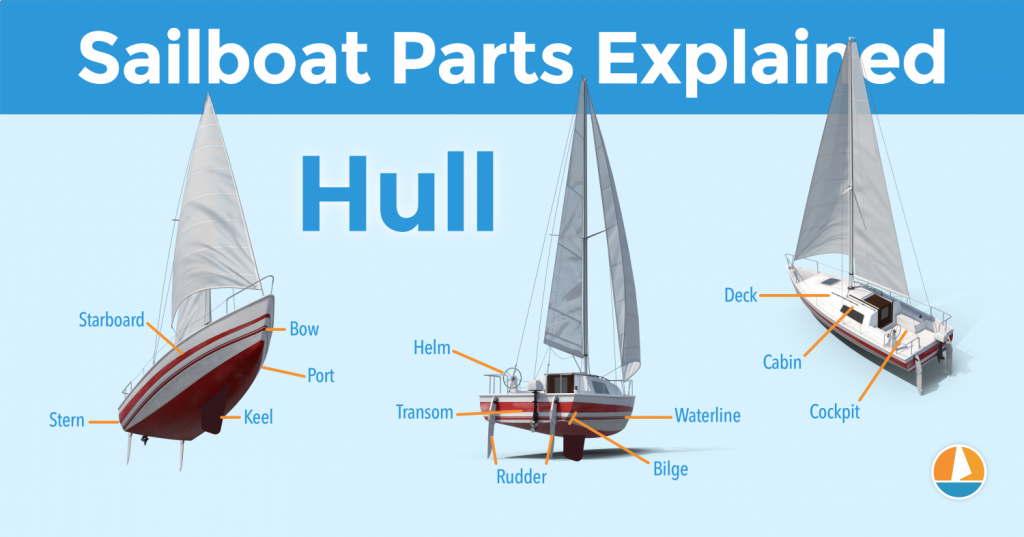

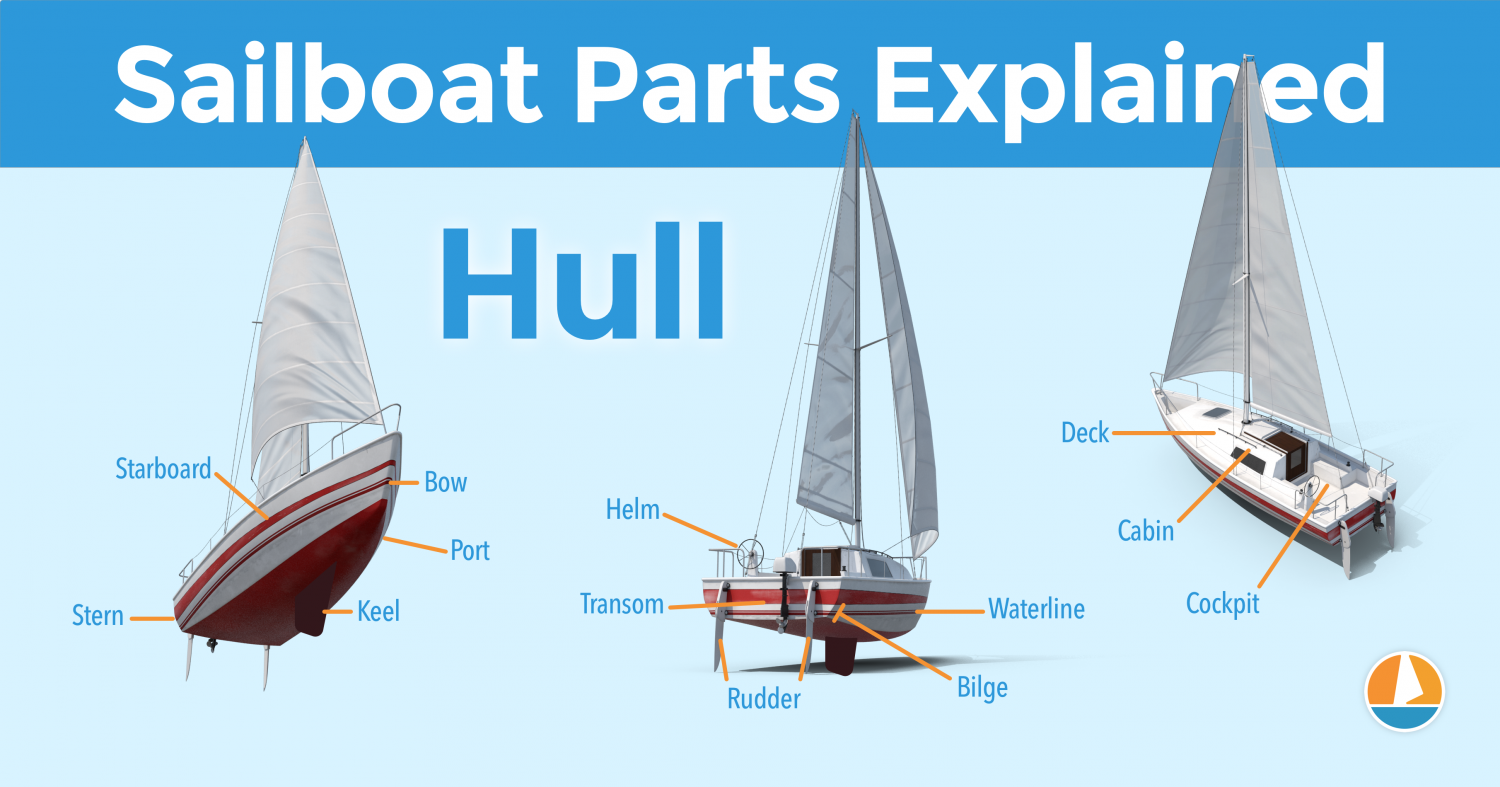

The foretriangle is the triangular area formed by the mast, deck, and forestay. Learn more terms here .

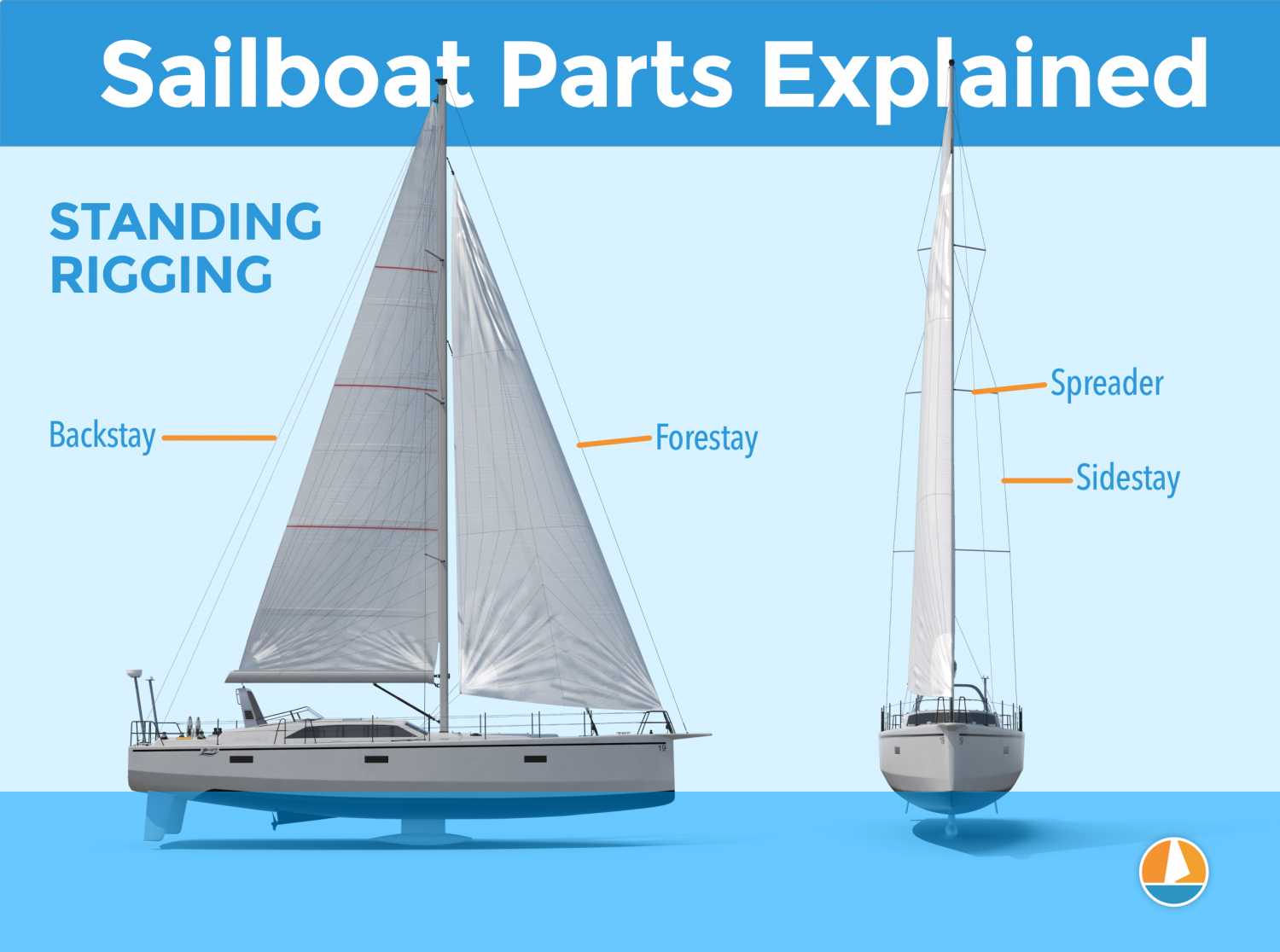

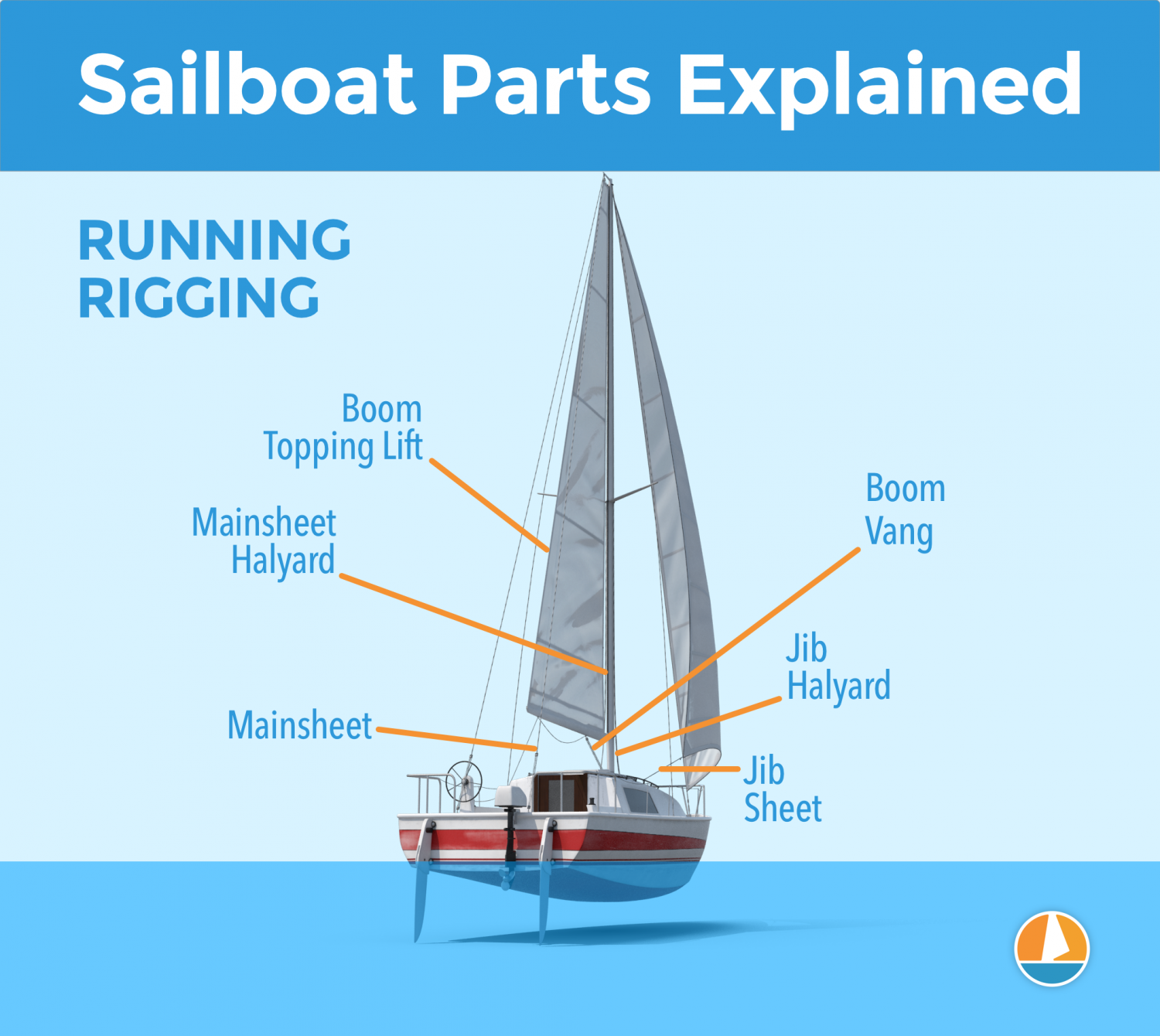

Like other headsails, the Jib is usually rigged on a furling system attached to the forestay , making it easy to operate. The Jib can also be rigged with a self-tacking system, making upwind sailing easy for you, whether you want to cruise solo or with your friends.

How the Jib works on a sailboat

The Jib provides a sail area forward of the mast, allowing the boat to be steered and balanced effectively.

The curved shape of the sail creates a pressure differential. The outer, more convex side (leeward side) has a lower pressure than the inner, concave side (windward side). This pressure differential generates lift, which translates into forward propulsion, much like how an airplane wing produces lift.

How to rig a Jib

You can rig the Jib on either a furling system or directly to the forestay. Most modern sailing boats are equipped with a furling system, which is a long sleeve that runs from the top of the mast down to the bow and attaches to a drum on the bottom and a swivel on the top.

Take a closer look at this step-by-step process on how to rig the Jib to sail onto a furling system:

- Feed the Jib’s luff into the track on the furler’s sleeve with the top of the sail first and connect the head ring on the sail to the chackle on the swivel.

- Attach the Jib halyard to the swivel and hoist the sail up.

- When the sail is hoisted almost all the way to the top, you attach the sail’s tack to a shackle on the top of the drum.

- Put the halyard on a winch and winch it tight.

- Now you have to manually roll up the sail around the forestay and tie on the two sheets to the clew of the sail.

- Lead the two sheets on each side of the vessel’s side decks through the sheet cars, turn blocks, and back to the winches.

- Now that the sail is furled away, we need to tie the furling line onto the drum. You have to figure out how the furling line attaches, as it differs from system to system.

- Once the furler line is attached to the drum, ensure that it can wrap itself up freely.

- Pull the sail back out using one of your sheets and monitor that the furling line wraps on nicely.

- Leed the furling line through the blocks and funnels, through the jammer , and leave it next to the winch.

- Furl the sail away again using the furling line and ensure that the sheets run freely as you monitor your sail getting wrapped nicely around the forestay.

- Secure the furler line jammer and tidy up your two sheets. Make sure to secure the sheets around the winches.

So, you see now why most boats use furling systems? It is easy! Many larger sailboats even have electrical furlers, removing the need for the furling line.

How to use, reef, and trim a Jib

To use the Jib, you wrap the furler line around the winch, open the jammer, and pull on either of the sheets, depending on which tack you are sailing on. You should hold on to the furler line to prevent the sail from unfurling itself uncontrollably, especially in strong winds. Trying to catch it if it starts running can injure your hands, so be careful! I’m speaking from experience here; burned hands are “No bueno.”

You can now unfurl the entire sail or a part of it. Once the full sail, or the amount you desire, is out, adjust your car position and tighten the sheet.

How to reef a jib

You do the opposite as the above to reef the sail or furl it back in.

Ease off the working sheet, but keep it on the winch. At the same time, pull in on the furler line either manually or on the winch. Remember to move the cars forward and re-tighten the sheet if you are reefing away only a part of the Jib.

How to trim a jib

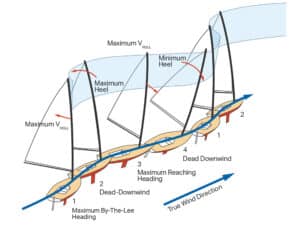

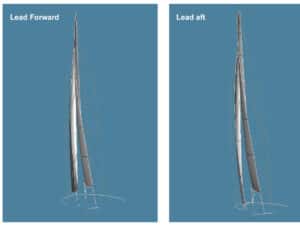

Adjusting the sheet cars and sheet tension is important to obtain an optimal sail shape in the Jib. Finding this balance is what we call sail trim . I’m not going too deep into sail trim here, as it is a topic for itself, which will require a separate article,.

But here is a rule of thumb:

You want the leech and foot of the sail to form an even “U” shape on any point of sail . When sailing upwind, you usually move the car aft. When bearing off the wind, you move the car forward.

The goal is to apply even tension on both the foot and the leech. When you reef the sail, you’ll also want to move the car forward to adjust for the reduced sail area. Sailing downwind doesn’t require the same fine-tuning as upwind sailing.

Four tips for sailing upwind:

- Winch up the jib sheet until the leech stops fluttering and the foot has a nice, even “U” shape.

- You must move the sheet car forward if the foot is tight and the leech flutters.

- Move the sheet cars aft if the leech is tight and the foot flutters .

- If the wind increases and the boat starts to heel excessively, you can either ease off the sheet or adjust your course more head to wind.

You should play around and experiment with sail trim, as every boat behaves differently. Trimming sails is an art that takes time to master. Staysails, Jibs, and Genoas are trimmed the same way, but the car positions will be different due to their size and shape differences. Once you learn how to trim a Jib, you’ll be able to trim any headail and even a storm jib or a spinnaker.

Sailing with more than one Jib

Sailing with multiple jib sails can be beneficial on longer downwind passages. Most furling systems have two tracks, allowing you to have two Jibs on the same furler, making this setup easy to reef. You can do the same with Yankees and Genoas, depending on what you have available in your boat.

Some sailboats have two or more forestays, allowing them to have two individually furled Jibs. This is usually called a cutter rig. Most Cutter rigs, however, use a Staysail on the inner forestay and a Yankee sail on the outer, but this versatile rig allows you to experiment with many setups.

Exploring the different parts of the Jib

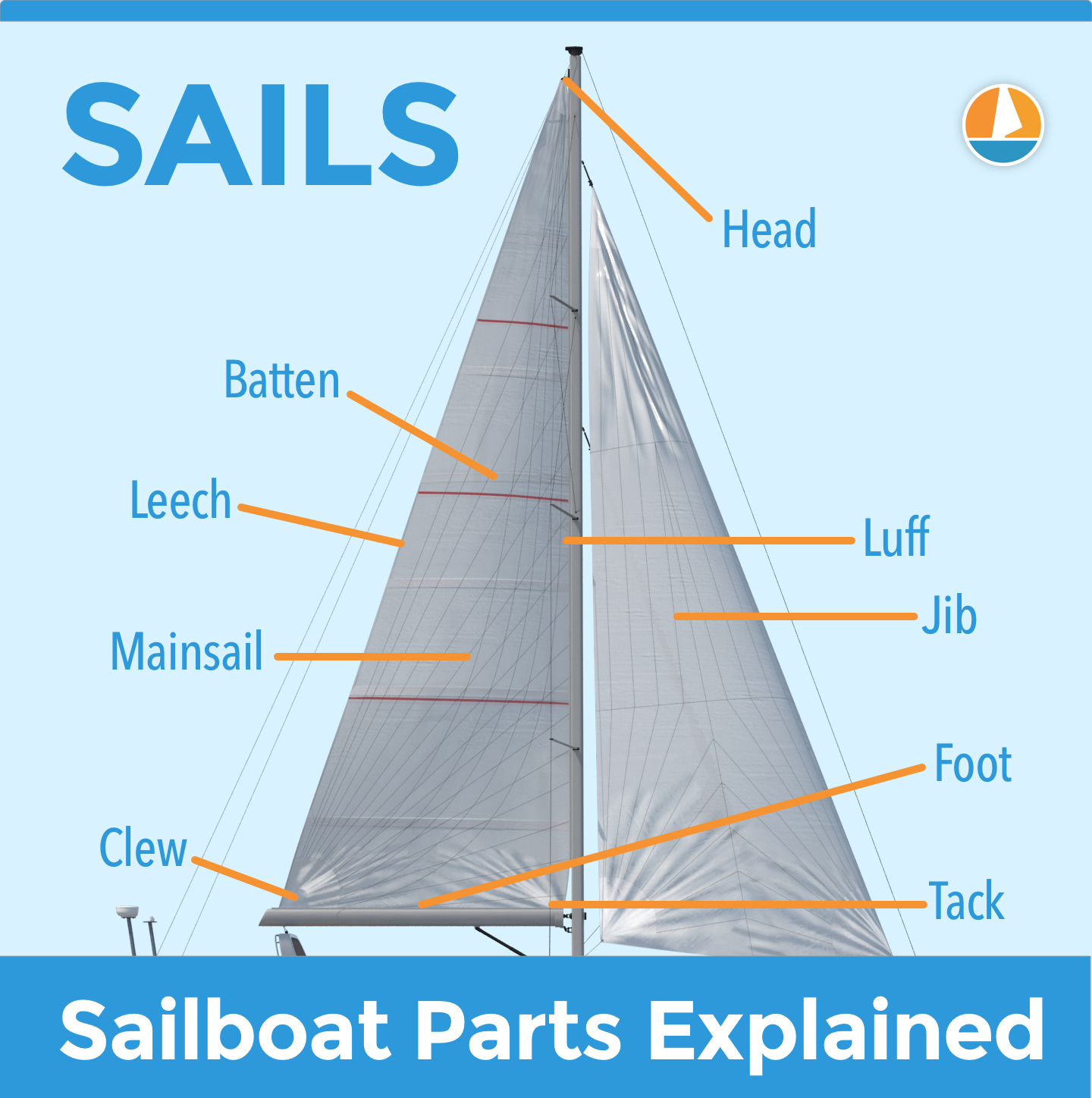

Head: The head is the top corner of the Jib. It typically has a ring in the top corner that attaches to the Jib halyard or the top swivel for furling systems.

Leech: The leech is the aft part of the rib, located between the clew and head.

Luff : A Jib’s luff is the front part between the tack and head. Jibs can be equipped with luff foam to help maintain their shape when partially reefed on a furler.

Clew : The clew is the aft lower corner of the jib where the sheets are attached.

Tack : The tack is the lower, forward corner of the Jib. The tack is connected to a furler drum on the forestay on most sailboats. Vessels using traditional hank-on headsails connect the tack to a fixed point on the bow.

Foot : The foot of the Jib is the bottom portion of the sail between the clew and the tack.

Telltales: Telltales are small ropes, bands, or flags attached to the front of the Jib’s leech to help us understand how the wind affects the sail and allow us to fine-tune the trim for optimal performance.

Commonly used materials for the Jib

The most common material used for Jib’s today is Dacron woven polyester, followed by CDX laminate due to the relatively affordable price. Continuing up the range, we find woven hybrids like Hydranet, Vectran, Radian, and other brands.

Then, we have advanced laminates with Aramids, carbon, kevlar, and more exotic materials. At the top of the spectrum, we find the latest technology in DFi membrane sails like Elvstrøms EPEX or North Sails 3Di, which comes at a premium price tag.

These days, however, modern technology has given us warp-oriented woven cloth, which is becoming a popular option due to its increased ability to keep shape over time without stretching as much as traditionally cross-cut dacron sails. ProRadial, made by Contender and Dimension Polyant, is a good example. North Sails has an excellent article that goes in-depth on sail materials.

The difference between a Jib and a Genoa

The difference between a Jib and a Genoa is that the Jib is a headsail that does not overlap the mainsail, while the larger Genoa is designed to overlap the mainsail. While the smaller Jib is excellent at pointing upwind and easier to handle, the larger Genoa excels on any points of sail with the wind behind the beam.

Genoas are usually larger than 115% of the foretriangle , with sizes ranging from 120% to 150%. They are often used on yachts with masthead rigs and smaller mainsails but are also common on fractional rigs.

How to Maintain and Care for Your Jib Sail

Good maintenance and care of your Jib will ensure optimal performance and minimize wear and tear. Check out these tips on how to maintain and protect your Jib:

- Rinse the Jib with fresh water regularly and leave it up to dry before packing it away. Proper drying will prevent moisture and mildew.

- Give the sail a service once a year. Check for any damaged seams and repair them if necessary. If there are any chafing marks, reinforce the sail with patches on chafe points and add shafe guards to the equipment it rubs against.

- Protect the sail from UV rays by keeping it packed away when not in use. A furling Jib can be protected by adding a UV strip to the foot and leech.

I also wrote an article on how to make sails last longer .

Final Words

We have talked a lot about the Jib’s features and how it works in this article. I recommend you to head out and set sail to get some experience and play around with your sails. If you don’t have a boat, chat around in your nearest marina; someone will for sure bring you along for a sail. I know I would.

Remember to experiment with sail trim and practice tacking and maneuvering the vessel with the sail on both the port and starboard sides.

If you still have questions, check out the frequently asked questions section below or drop a comment in the comment field. I’ll be more than happy to answer any of your questions!

PS: Explore more sails in my easy guide to different types of sails here .

FAQ – The Jib Sail Explained

When to use a jib sail.

The Jib is an excellent sail for most conditions, especially when cruising at any angle towards the wind. The Jib has a benefit over the Genoa in strong winds as it is easier to handle, and its smaller size makes it more effective than a reefed Genoa when sailing to windward.

Can you sail with just the Jib?

It is possible to sail with just the Jib alone, and it works exceptionally well downwind on deep angles where the mainsail usually would have blocked off the wind.

Can you sail upwind with just the jib?

It is possible to sail upwind with just the Jib, but most sailboat owners prefer to balance their boats by flying their mainsail combined with theiJib when sailing to windward.

What is the difference between a Genoa and a Jib?

The Genoa is different from a Jib sail as it is larger and overlaps the mainsail, whereas the Jib is smaller and does not overlap the mainsail.

Sharing is caring!

Skipper, Electrician and ROV Pilot

Robin is the founder and owner of Sailing Ellidah and has been living on his sailboat since 2019. He is currently on a journey to sail around the world and is passionate about writing his story and helpful content to inspire others who share his interest in sailing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How To Use a Jib on a Sailboat (Here’s What You Need To Know)

If you’re a sailor looking to maximize your control of your sailboat, learning how to use a jib is essential.

A jib is a triangular sail mounted at the bow of the boat and is a key component in controlling the speed and direction of your boat.

This article will provide an overview of what a jib is and how to use it, including understanding the forestay, adjusting the jib sheet, positioning the jib, trimming the jib, and practicing with a jib.

Plus, we’ll provide a few tips to ensure you get the most out of your jib.

Read on to discover everything you need to know to use a jib on a sailboat.

Table of Contents

Short Answer

A jib is a triangular sail that is set on a stay in front of the mast of a sailboat.

To use a jib, the sheet attached to the clew of the sail must be pulled in to bring the sail around so that the wind fills it.

The sheet should be adjusted to keep the sail trimmed properly while sailing.

The jib can also be used to help turn the boat, by easing the sheet and allowing the sail to swing out to the windward side.

What is a Jib?

A jib is an essential component of a sailboat, as it provides the boat with increased control and maneuverability on the water.

A jib is a triangular sail that is mounted on the front of the boat, also known as the bow.

It is attached to the forestay, a metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

The jib is used to create lift, allowing the sailboat to move more quickly and efficiently through the water.

The jib works in conjunction with the main sail, providing additional power and control when sailing.

It can be adjusted to the wind direction and the desired angle of the sailboat, which can help to increase the speed of the boat and improve its performance in different wind conditions.

Additionally, the jib can also be used to help the boat turn and maneuver in tight spaces, such as when entering a harbor or marina.

In order to use a jib on a sailboat, the jib must first be raised and secured to the forestay.

This is usually done by attaching it to the luff groove, which is a groove along the edge of the sail that slides onto the forestay.

Once the jib is secure, the jib sheet is used to control the jibs angle and direction of travel.

The jib should be adjusted according to the wind direction and the desired angle of the sailboat.

Finally, the jib trim is adjusted, which will keep the jib in the optimal position for smooth sailing.

With practice, sailors can become proficient in using a jib to their advantage.

Understanding the Forestay

When it comes to using a jib on a sailboat, understanding the importance of the forestay is essential.

The forestay is the metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

It plays an integral role in the efficiency and maneuverability of the boat, as it is the connection point for the jib sail.

Without the forestay, the jib cannot be raised and secured, which limits the boats performance.

Knowing how to properly adjust and maintain the forestay is key to using a jib correctly and efficiently.

When raising the jib, the forestay should be taut to hold the jib in place.

It is essential to make sure that the forestay is not too loose, as it could cause the jib to flutter and lose its shape.

Additionally, the forestay should not be too tight, as it will increase the strain on the jib and could cause damage.

The tension of the forestay should be adjusted to achieve the optimal balance between stability and sail shape.

In addition to ensuring the proper tension of the forestay, it is important to pay attention to the alignment of the forestay with the mast.

If the forestay is misaligned with the mast, it can disrupt the wind flow and cause the jib to flutter.

This fluttering can be prevented by ensuring the forestay is properly aligned.

By understanding the role of the forestay and how to adjust it correctly, sailors can use a jib to their advantage and improve their sailing performance.

With practice, sailors can become proficient in using a jib and the forestay to achieve the desired angle and direction of travel.

Adjusting the Jib Sheet

Adjusting the jib sheet is a key part of using a jib on a sailboat.

The jib sheet is a rope or line that is attached to the clew of the jib and runs to the cockpit or winch, allowing the sail to be adjusted to the appropriate position and angle.

It is important to ensure that the jib sheet is securely attached to the clew of the jib before sailing.

Additionally, the jib sheet should be adjusted to the correct tension depending on the wind conditions.

If the jib sheet is too loose, the jib will flog and be ineffective.

If the jib sheet is too tight, the sail will be over-trimmed and the boat will be slower.

To find the optimal jib sheet tension, try different tensions and angles and make sure to pay attention to how the boat responds to the changes.

With practice, you will be able to determine the best tension for the jib sheet.

Positioning the Jib

Positioning the jib on a sailboat is an important step for any sailor looking to make the most of their sailing experience.

While the jib is an essential component of a sailboat, it is also essential to understand how to properly use it.

In order to use a jib, the jib must first be raised and secured to the forestay, which is the metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

The jib sheet is then used to control the jibs angle and direction of travel.

It is important to pay attention to the wind direction and adjust the jib accordingly.

The jib should be adjusted to be perpendicular to the wind direction, and this angle should be kept consistent during the sail.

This helps to ensure that the sailboat will move in the desired direction, and that the jib will provide optimal lift.

Sailors should also adjust the jib trim, which is the tension on the jib sheet.

The jib trim should be adjusted according to the wind conditions to keep the jib in the optimal position for smooth sailing.

Too much tension on the jib sheet can cause the jib to backwind, which can slow down the boat and make it difficult to maneuver.

Too little tension can cause the jib to luff, which can reduce the lift provided by the sail.

Finally, with practice, sailors can become proficient in using a jib to their advantage.

Utilizing the jib to its fullest potential can help to optimize speed and control, and make the sailing experience even more enjoyable.

Trimming the Jib

Trimming the jib is a crucial part of using a jib on a sailboat.

This is the step that will ensure the jib is in the optimal position for the best sailing experience.

The jib trim should be adjusted according to the wind direction and the desired angle of the boat.

When the wind is coming from a certain direction, the jib will need to be adjusted accordingly.

If the wind is coming from the starboard side, the jib should be adjusted to the right.

If the wind is coming from the port side, the jib should be adjusted to the left.

In addition to adjusting the jib to the wind direction, the jib trim should also be adjusted to the desired angle of the boat.

This will help to maximize the performance of the boat and ensure that the jib is in the best position for sailing.

The jib trim should be adjusted so that the angle of the jib is roughly the same as the angle of the boat.

This will ensure that the jib is properly positioned and will help to maximize the performance of the boat.

Finally, the jib trim should be adjusted periodically to ensure that the jib is in the best position for sailing.

This can be done by observing the jib and adjusting the trim as necessary.

By trimming the jib correctly, sailors can improve their sailing experience and make the boat faster and easier to navigate.

Practicing with a Jib

Using a jib on a sailboat requires practice and skill to become proficient.

While learning the basics of how to use a jib is important, it is also necessary to gain an understanding of the wind and how it affects the sailboat.

By learning the basics of how a jib works and how to adjust it, sailors will be able to use the wind to their advantage.

The jib should be raised and secured to the forestay, which is the metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

Next, the jib sheet is used to control the jibs angle and direction of travel.

This is done by adjusting the tension on the sheet, which will affect the angle of the sail and the direction of the boat.

The jib trim is then adjusted to keep the jib in the optimal position for smooth sailing.

To practice using a jib on a sailboat, it is important to start slowly and focus on learning the basics.

Begin by familiarizing yourself with the wind and understanding how the direction of the wind affects the sailboat.

Once you understand the basics, you can experiment with different angles and settings to see how the jib affects the boats speed and direction.

As you become more comfortable and experienced with using a jib, you can begin to practice more advanced maneuvers, such as tacking, jibing, and reefing.

These maneuvers can be used to control the speed and direction of the sailboat, and can make the sailing experience more enjoyable.

Sailing with a jib can help to make the boat faster and easier to navigate, and can enhance the sailing experience.

By understanding the basics of using a jib and practicing regularly, sailors can become comfortable and confident in their ability to use a jib to their advantage.

Tips for Using a Jib

Using a jib on a sailboat is a great way to increase control and maneuverability while sailing.

A jib is essentially an additional sail that can be attached to the forestay, a metal cable running from the bow of the boat to the mast.

It is important to know the basics of how to use a jib in order to maximize the sailing experience.

Here are some tips to help you get started.

First, it is important to ensure that the jib is properly raised and secured to the forestay.

This can be done by attaching the jib’s clew, or the corner of the sail, to the forestay using a wire or cable.

It is also important to make sure that the jib is taut and free of wrinkles or creases.

Once the jib is in place, the jib sheet can be used to control the jib’s angle and direction of travel.

This is done by adjusting the jib sheet, which is a rope connected to the corner of the jib, in order to change the tension of the sail.

It is important to adjust the jib sheet according to the wind direction and the desired angle of the sailboat.

This will ensure that the jib is in the optimal position to take advantage of the wind.

Finally, the jib trim should be adjusted.

This is done by using the jib sheet and the jib halyard, which is a rope that runs from the top of the jib to the deck.

By adjusting the tension of the jib halyard, the angle of the jib can be changed to keep it in the best position for sailing.

Using a jib correctly can help to improve the sailing experience and make the boat faster and easier to navigate.

By following the tips outlined above, sailors can get a better understanding of how to use a jib on a sailboat and maximize their sailing experience.

Final Thoughts

Using a jib on a sailboat can make sailing smoother, faster, and more enjoyable.

With a solid understanding of the components and the proper technique, anyone can become a pro at using a jib.

It just takes a little practice, patience, and understanding of the wind direction.

With the right know-how, you’ll be sailing like an expert in no time!

James Frami

At the age of 15, he and four other friends from his neighborhood constructed their first boat. He has been sailing for almost 30 years and has a wealth of knowledge that he wants to share with others.

Recent Posts

Does Your Boat License Expire? Here's What You Need to Know

Are you a boat owner looking to stay up-to-date on your license requirements? If so, youve come to the right place! In this article, well cover everything you need to know about boat license...

How to Put Skins on Your Boat in Sea of Thieves? (Complete Guide)

There is a unique sense of pride and accomplishment when you show off a boat you customized to your exact specifications. With Sea of Thieves, you can customize your boat to make it look like your...

- AROUND THE SAILING WORLD

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Email Newsletters

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

- America’s Cup

- St. Petersburg

- Caribbean Championship

- Boating Safety

Sailboat Winch Technique 101

- By Sean Clarkson

- Updated: May 2, 2014

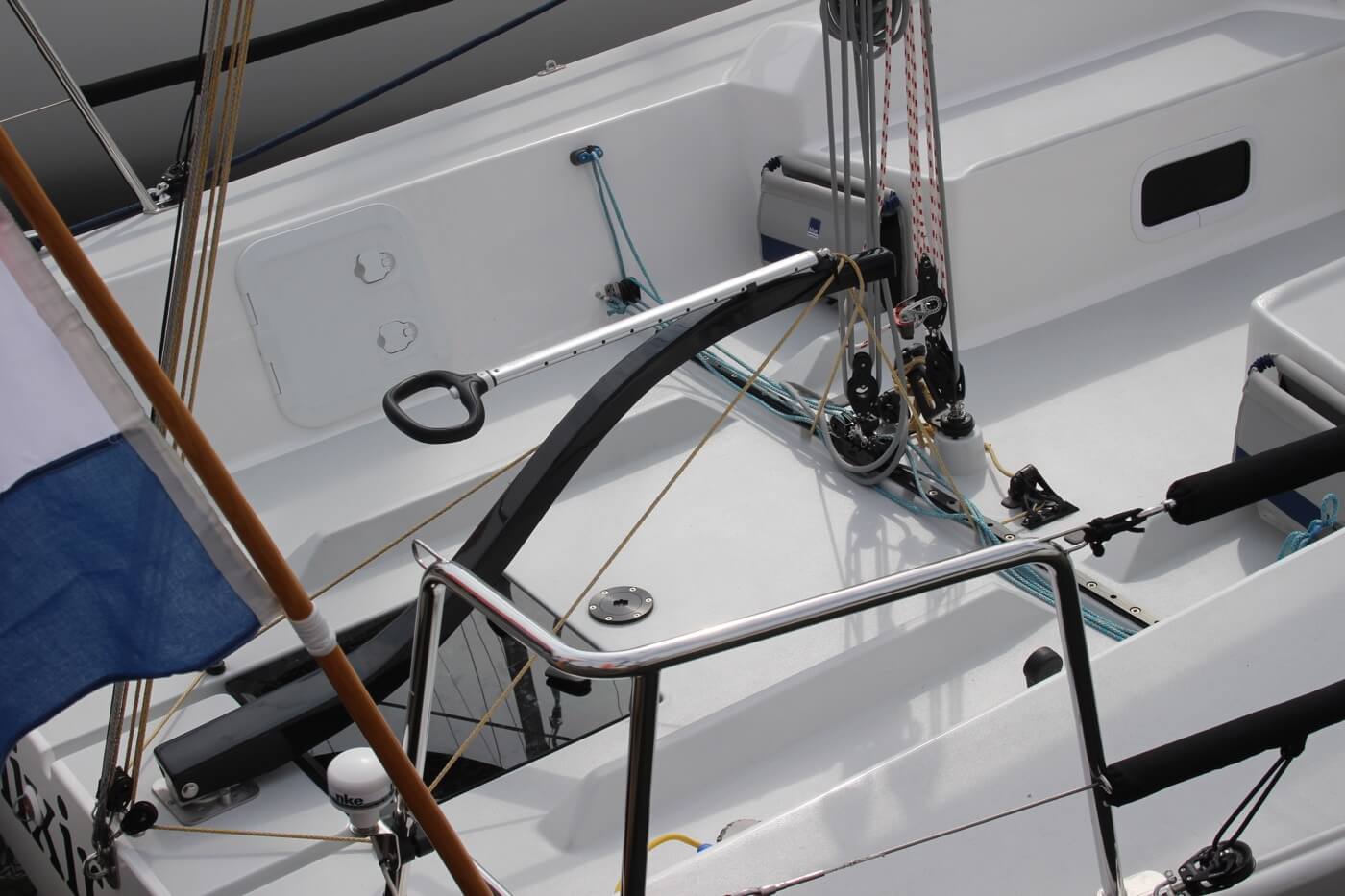

Loading a sailboat winch in the correct direction is the first step. Many big-name sailors have fallen victim to this. If there’s any doubt, especially if your boat has counter-rotating winches, put arrows on the top of the winch or on the deck around the base of the winch. It may not look cool, but neither is putting turns on incorrectly.

It’s important that the sheet is led to the winch at the correct height. If it’s too low, it can slip down the drum, and if it’s too high, it can lead to regular overrides. The sailing winch manufacturer can provide a drawing with the ideal angle for the lead.

The number of wraps you start with is really a function of rope diameter, drum diameter, and drum surface quality. Smaller-diameter line may require more wraps to prevent the line from slipping on the drum. In general, though, two wraps is a good starting point, and as load increases, you can add more.

Don’t be surprised if, for example, the jib winch requires two wraps on one side and three on the other. The way sailboat winches load, you gain or lose half of a wrap because of where the line starts and finishes on the winch. And with sheets moving at high speed, make sure there’s no slack in the lazy sheet before you start pulling because you can easily end up with an override.

If you do happen to get an override, don’t keep it a secret from the rest of the crew—it’s better that they know, especially if you’re around other boats and need to dip or tack. If you have time, the best method to remove the override is to reverse the lead direction of the sheet (or halyard) and pull the override out, either by hand or by using another winch. Be careful when the override clears itself and gets reloaded. If the override is on the jibsheet and time is short, the best option is to cut the sheet at the clew when tacking. After the tack, reattach the sheet. If you cut the sheet at the winch, it will likely end up being too short. Trust me, I’ve seen it happen.

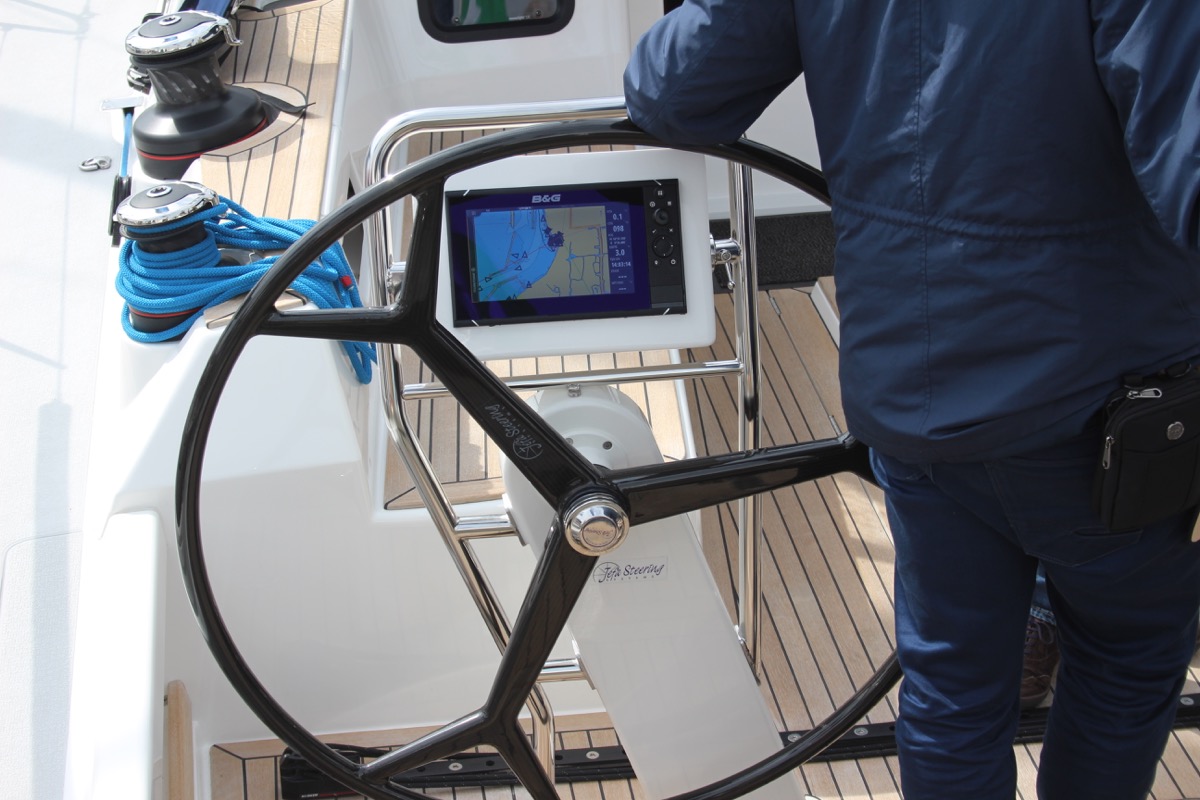

Winch gearing is all based on required line speed, which means being in the right gear to trim the sail in smoothly at the same rate the apparent-wind angle changes. Driving a sail in and stalling it isn’t fast. On a three-speed winch, first gear is your gross tune for pulling in the majority of the line: one rotation of the handle generally equals one drum turn. In second gear, you’re finishing your trim with the line carrying a lot more load: more winch-handle rotations are required for one drum rotation. Third is your high-load, fine-tune gear.

If your winch has a first-gear button, you’re in luck for jibing asymmetric sails or big genoas. Keeping your momentum going is key. Anticipate when you need to change gears before the load gets too high.

There are a few things you can do to make it easier when using a handle-driven winch with a first-gear button. For example, never put the winch handle directly over the button. This prevents the button from popping up to give you third gear. Also, if you leave the winch handle in the winch, try to leave it pointing to leeward—this helps prevent the handle from swinging down by itself (if you hit a wave, for example) and disengaging first gear.

Speaking of winch handles, a longer handle is a great “extra” gear. Most manufacturers produce both 8-inch and 10-inch handles. If you need more speed, use the short handle. If you need just grunt, say for the backstay, the 10-inch handle gives you 20 percent more power.

There are a few options for the actual handle-grip style and locking mechanism, but in short, the double handle is good for big loads when speed is not as important. The single handle is easy and quick, which is better for smaller boats and lower loads. The speed-grip handle is, in my opinion, the best all-around because it covers both options.

In terms of locking mechanisms, I prefer the newer handles with quick one-handed grip levers that are fast and easy to engage and disengage. If the handle is wobbly or hard to disengage from the winch, it’s probably time to buy a new handle.

A lot of winch technique comes down to experimentation and communication between the trimmer and the grinder. The grinder must be observant of the sail’s needs and anticipate what is required. For example, catching the curl on a spinnaker early requires less grinding and less steering by the helmsman, which equates to speed. If you’re grinding, always watch the telltale signs: the sail itself, the breeze, the helm, and the opposition.

Every boat’s layout is different, so the most efficient stance varies. However, the goal is to get your body over the winch and have a secure position for your legs. A huge amount of your power comes from your core and legs, so you need to be well braced. Where you are depends on many variables, but in light air try to be forward and to leeward. In heavy air, maximize your weight to windward. Either way, stay in a mobile position when you’re not grinding; your body weight is critical to the kinetics of the boat, such as rocking the boat down out of a jibe and roll tacking.

This article first appeared in the March/April 2014 issue of Sailing World. To read more sailing tips, click here.

Winch Wraps

Sean Clarkson

- More: Sailing How To

- More How To

The Wisdom of Augie Diaz

Why S-Turns, Roll Jibes and Roll Tacks Are Fast

The Path to Consistent Boatspeed

Headsail Trim Tips For Floating Leads

Brauer Sails into Hearts, Minds and History

Anticipation and Temptation

America’s Offshore Couple

Jobson All-Star Juniors 2024: The Fast Generation

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Attainable Adventure Cruising

The Offshore Voyaging Reference Site

- Offshore Sailboat Winches, Selection and Positioning

We have already published two chapters on offshore sailboat cockpits in our How To Buy a Cruising Boat Online Book, but even so there are still a bunch of selection criteria I have not covered, so let’s dig into winches, both those in the cockpit and generally.

Why It Matters

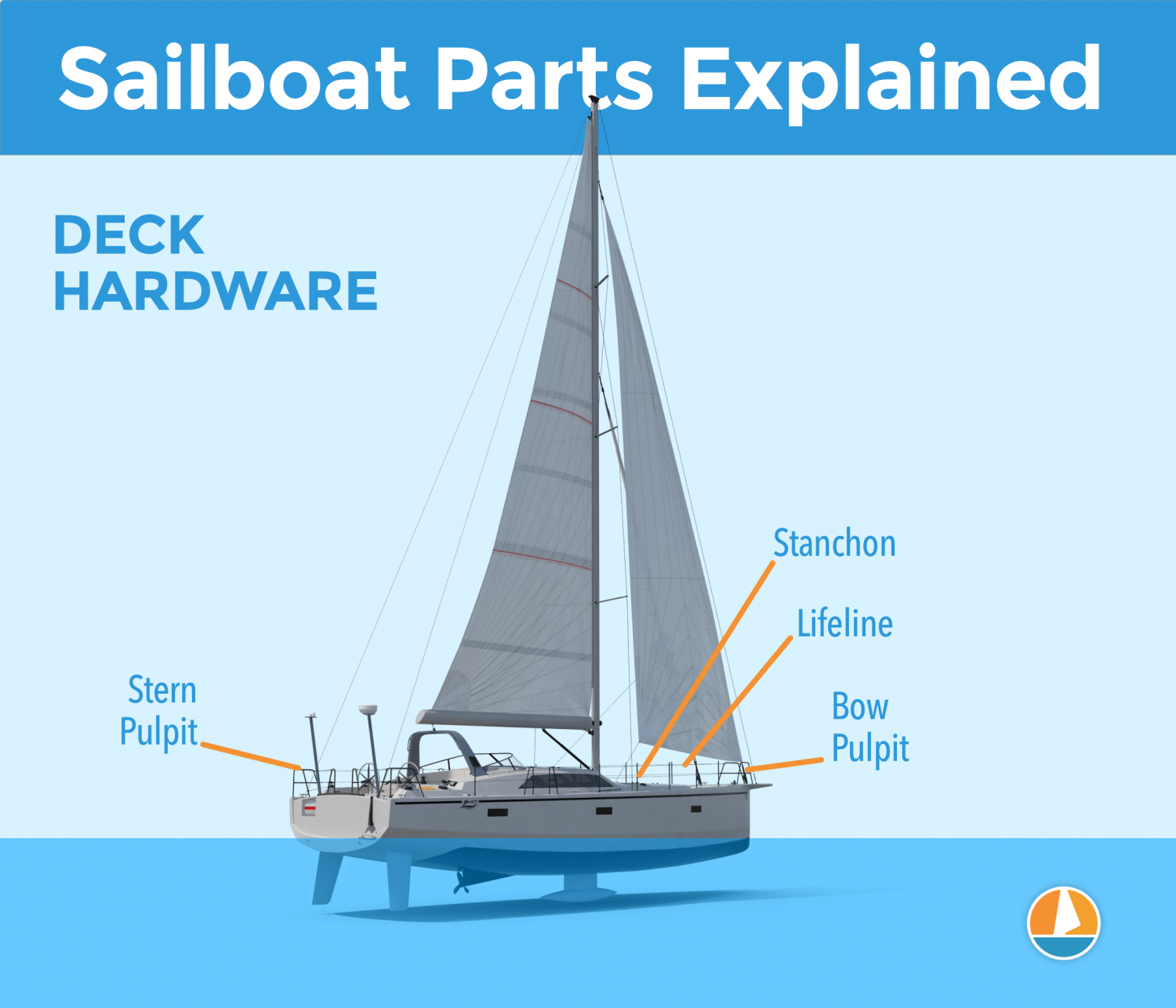

With offshore sailboats the devil is absolutely in the details and never more so than when we come to winch setup. A poorly-positioned winch:

- Can result in repeated injuries, particularly to shoulders, neck and back.

- Will force the crew into an awkward position so they can exert far less force on the handle than they would be able to otherwise.

- This in turn can require the installation of electric winches, with all of the associated expense and potential dangers.

- Can encourage crew members to adopt unsafe positions, often outside of the cockpit and in the way of the boom.

Given that, let’s look at how to identify boats with winches done right:

Login to continue reading (scroll down)

Please Share a Link:

More Articles From Online Book: How To Buy a Cruising Boat:

- The Right Way to Buy a Boat…And The Wrong Way

- Is It a Need or a Want?

- Buying a Boat—A Different Way To Think About Price

- Buying a Cruising Boat—Five Tips for The Half-Assed Option

- Are Refits Worth It?

- Buying a Boat—Never Say Never

- Selecting The Right Hull Form

- Five Ways That Bad Boats Happen

- How Weight Affects Boat Performance and Motion Comfort

- Easily Driven Boats Are Better

- 12 Tips To Avoid Ruining Our Easily Driven Sailboat

- Learn From The Designers

- You May Need a Bigger Boat Than You Think

- Sail Area: Overlap, Multihulls, And Racing Rules

- 8 Tips For a Great Cruising Boat Interior Arrangement

- Of Cockpits, Wheelhouses And Engine Rooms

- Offshore Sailboat Keel Types

- Cockpits—Part 1, Safe and Seamanlike

- Cockpits—Part 2, Visibility and Ergonomics

- Choosing a Cruising Boat—Shelter

- Choosing A Cruising Boat—Shade and Ventilation

- Pitfalls to Avoid When Buying a New Voyaging Boat

- Cyclical Loading: Why Offshore Sailing Is So Hard On A Boat

- Cycle Loading—8 Tips for Boat and Gear Purchases

- Characteristics of Boat Building Materials

- Impact Resistance—How Hull Materials Respond to Impacts

- Impact Resistance—Two Collision Scenarios

- Hull Materials, Which Is Best?

- The Five Things We Need to Check When Buying a Boat

- Six Warnings About Buying Fibreglass Boats

- Buying a Fibreglass Boat—Hiring a Surveyor and Managing the Survey

- What We Need to Know About Moisture Meters and Wet Fibreglass Laminate

- US$30,000 Starter Cruiser—Part 2, The Boat We Bought

- Q&A, What’s the Maximum Sailboat Size For a Couple?

- At What Age should You Stop Sailing And Buy a Motorboat?

- A Motorsailer For Offshore Voyaging?

- The Two Biggest Lies Yacht Brokers Tell

As has been so often the way this past year or so, you put up articles that are downright spooky in their timing. I just got home after a spending a few hours templating my winch and clutch layout on my coachroof – so this article has been a huge sanity check.

I think I’ve managed to tick all the important boxes. My boat has a grand total of 11 winches festooned over it, 4 forward on or near the mast for the halyards and reefing lines (and I’ve listened to your stern admonitions on this despite almost all local opinion going the other way), then 3 on the coachroof just forward of the cockpit, and finally 2 each side on the cockpit coaming.

Because my staysail track is already on the coachroof, the sheets go to the 2 outboard winches up there. In effect this gives me the ‘three winches each side’ you suggest. The same winches are also used for the minor mainsail trimming controls outhaul and vang, and the two traveller control lines.

The centre coach roof winch is used for the mainsheet only – not ideal but I’m going to live with it as the easiest solution to get me back into the sea. (The coachroof is low enough that standing astride the cockpit seats we get a good position to operate them.)

The cockpit primaries are jib sheet only, but the secondaries have four different lines, furlers, preventers, whisker pole and running backstay terminating on them. Trying to shift the mainsheet back there as well just struck me as too hard – even though I can see the advantages. The blocks and jammers needed to make it work are going to be complicated enough as it is.

I just counted them all up – a total of 30 different lines! Deciding on how I wanted to run them all has been one of the most drawn out and troublesome decisions I’ve had to make so far, and I want to convey just how much your input here at MC has influenced my thinking for the better. I couldn’t quite get to the ideal, but close enough that I’m really looking forward to getting it finally done!

Agree about the timing!

Only 11! Bah! 🤣 My old girl has thirteen – seven in the cockpit, two on the mast and – (this is where I have doubts) – four on the coachroof, under the gooseneck (reef, outhaul, topping lift, kicker). I can scrap the kicker and topping lift by fitting an hydraulic strut as per MC, and move the reefing winch to the mast. Then we will be even!

Now, now, boys, let’s play nice 🙂

Winches “r” us! Old picture from two years ago. The halyard, reefing and mainsheet winches are now self tailing and I just have to raid the piggy bank and talk to Mr Harken about replacing the six flat top monsters in the cockpit… your advice about not going for electric winches is very welcome!

Glad it was useful. As you say, getting this right is a real brain stretcher. Don’t worry too much about the mainsheet, there are always going to be compromises. In our case the less than idea winching position for the staysail comes to mind.

The other thing to realize is that you are not going to get this right the first time no matter how hard you try, and that realization can actually be a stress reducer, at least when we remember that changing this stuff is not that horrible, particularly on a fibreglass boat. Point being that getting a really good deck layout is a process, not a destination. After 30 years of steady improvement (starting from a good place) MC is about 95% right, but I can still think of little tweaks that would improve things further.

any thoughts on how much of a compromise are standard winches with Barton Winchers compared to self-tailing winches?

I have no experience with them yet, but I’ve got a pair of winches nearly for free and been contemplating getting rid of the staysail boom and using these standard winches with Winchers to sheet the staysail. Say, if you were forced to choose, which of these would be the lesser evil: staysail boom or non self-tailing winches?

I had a staysail boom for 29 years and whilst it was master of the foredeck when the sail was set, one could always drop the staysail on entering an anchorage. One does lose some horsepower but one can hank on a bigger staysail… on the other hand trying to sheet a staysail every tack with sub optimal winches is a pain in the neck. IMHO, fwiw…

Thank you for your opinion, Andrew.

Maybe I should have said that I’m talking about a staysail on a cutter. If need to short-tack, I tend to drop the staysail altogether and use just the jib-top, which is sheeted to self-tailing winches. So, I’m not sure how much of a pain in the neck it would be in practice. Definitely more work than when it tacks by itself, of course.

Tacking the staysail on a cutter, even one the size of MC, is so easy that I would always get rid of the boom. But then I’m a total deck clutter hater: https://www.morganscloud.com/2011/02/25/clear-the-decks-for-action/

Hi John, Andrew, Alex and all, John, agree completely about the staysail being a doddle to tack. When timing is good, snubbing the sheet before it fills pretty much precludes a need to winch. At most, a few inches is needed. For me, a chance to roll up the jib-topsail and short tack into an anchorage is just plain fun: no real work, total control (little worry about close-to-land gusts), good visibility, a chance to look around, no waves: what is not to like. My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

I agree, and as long as the water is smooth, a faster option than many would expect.

Hi John, Yes, agreed. It amazes me how easy it is to move a well-designed hull in flat water when there is little wind. I sometimes think that every boat should have as one of its base reported stats the force necessary (dynameter?) to pull it through the flat water on a calm day at, say, 6 knots. I imagine that would be an informative piece of information relatively easy to come by. My best, Dick

This was the home of the staysail boom – not in use in this picture.

Loverly photo of a loverly boat, thanks.

I tried the Barton years ago and found that while better than nothing they are not even close to a self tailing winch. That said, I would do most anything to get rid of a staysail boom, probably including using the Barton option and selling my first born child.

Thank you John. This answer is graphic enough to leave no doubt as to which way the boom should go.

Hi Phyllis The details in this picture are really interesting. What is orange fixture on your Spinlock left belt, and what kind of gloves are you using and do you like them? Would they be good for photography in Antarctica? How do you like the Musto Ocean gear? Thanks!

Picture of you at mast in today’s post:

https://etugri87v3i.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/JHH5-12909-700×[email protected]

Best wishes, Charles Charles L Starke MD FACP

Hi Charles,

If you put those questions into the search box, or check the topics page you will find short posts that answer them with the exception of the orange fixture which was a pre AIS POB alarm.

Hi John, Thanks for the article. Interested in your thoughts regarding winch placement on the Boreal 47.2: central winch in cockpit for halyards, centerboard, vang, reef lines (single line for first & second reef tack/clew, 3rd reef has line for clew and hook/cringle for tack). Two inboard winches for Genoa, staysail sheets. I am not sure whether the main sheet goes to central or aft winches. Maybe JFE will chime in. Best, David

Lot’s of tradeoffs there. So beyond what I can really do in a comment. Suffice to say that I generally prefer the Mk1 boats. My big problem with the Mk2 boats is the friction in the system from all the turns in the lines. On the positive side, the inboard primary winches look like they would be very efficient to use on the jib, and an improvement on the problem I identified in the article above.

Hi John, The set-up of the cockpit of the 47.2 (what you call mk2) is indeed very different from the earlier generation of Boréal. For us it is important to stress the fact that the 44.2 has the same principles of cockpit lay-out as the “original” 44 : one helmpost, all lines at the mast… That way we have a solution for the adapts of both philosophies…

Hi Jean-François,

Having now looked at renderings of both boats, I’m warming to the 47.2 and I think prefer it to the 44.2 because of the longer effective waterline for the same beam.

Hi David, I’m almost positive the smaller outboard winches are for the main sheet. I think the red for main and hard to see dark blue for jib are meant to show that.

Hi Michael,

Yes, I’m sure you are right. And a good position it is too, although there will be a lot of friction because of the convoluted lead which will make say jibing where a bunch of sheet must be pulled in quickly, a bit slow. My guess is all these Mk 2 boats are going to end up with electric winches for this reason, although an Ewincher might work too.

Hi John, Hi Michael, The genua winches are indeed the bigger winches you see on the inner side the cockpit… The ergonomy behind is that during a tack manoeuvre, one person can release the genua from one side AND pull it on the outer side… There is only more block (however at 90 %) than on the layout on the Mk1. Of course there is more friction than if the block was not there but the sytem really works fine. I hope that very shortly you can come and test it for yourself… Speaking of electrics : The ergonnomy is such that all lines can be brought back to the big central winch. If you electrify this one you can do all manoeuvres with that one electric winch. (the winch is oversized to a 65 size). JFE

Thanks for the confirmation on that. Given that you can stand over the winches in a safe and secure position, I totally get that winching the genoa will actually be easier and more efficient than on the Mk 1 boats, or my boat, definitely a good step forward. On the other hand, if I were having a 47.2 built I would ask you to put the reefing and halyard winches on the mast since I just don’t like the idea of using an electric winch from that far away from the action. That said, way, way, better than under the dodger since on the 47.2 you can at least see what you are doing.

I think I’m right in saying you would make that change, although the channels for the lines running aft would remain? If so, that’s probably good for resale value.

Anyway, I’m really looking forward to going sailing with you once this is over.

At the start of this article I became a little depressed. Must we really accept headsail sheet winches on the leeward coming as the only option? The suggested seat-height, kneeling, and other recommended ergonomics; and MC’s cockpit jackline solution mentioned elsewhere improve the situation but the operator still has her centre of gravity to leeward of her centre of support with the winch handle carrying the rest of the load. I really dislike sheeting to leeward and value the ability to place a foot to leeward of the load very highly. Perhaps it’s because I’ve sailed smaller boats than MC that bounce around more and on which crew weight position makes more of a difference. Full approval from me that Boreal at least, have brought them inboard. I have yet to see a better system than my old 1/4 tonner, which offered near-midship sheeting and a windward sheeting option, with the crew able to get a foot to leeward of the winch, all within the cockpit, and with no extra turnblocks. Might be hard to achieve in a larger cruising boat, but totally worth striving for IMHO.

Sure, I agree that leeward coming winches are less than ideal ergonomically. That said, bringing them inboard has downsides too. All these things are compromises. That said, wait for the A40 renderings…

Amen to the round-up problem being exacerbated by vang and main sheet controls out of reach of the helm! I’ve experienced this, for example, while pushing my luck too far with the spinnaker up in squall zones, and it is not fun. In my most serious round up, with the boat pinned on her ear, I was only able to depower the main by, while keeping the tiller hard to windward with my arms, stretching my leg across the companion way and releasing the vang clutch with my foot. I haven’t thought of a way to mitigate this hazard yet, except by sailing more conservatively. I am hesitant to move anything because the current set-up allows me to work the jib (or spinnaker) sheets, main traveler lines (and the topping lifts and after guys for two poles) while standing in one place (tiller between legs), so I can tack and jibe safely while single-handing. I have five winches on the cockpit coaming (primaries, secondaries and a spare), and two on the coach roof under the dodger. I’m also a fan of working the main halyard, reefing outhauls, and downhaul (Cunningham) at the mast, and have it set up so that I feel secure there even when it’s rough – cross bars between the forward and aft lowers give me a place to brace my back. I have four winches on the mast, two each side, that I use for the main, jib, staysail and spinnaker halyards, as well as for tensioning my removable inner forestay. A clutch for each halyard (and the inner forestay) is very handy, for example while hoisting, and of course allows winch sharing. I set my reefing outhauls using a winch on the forward end of the boom with a clutch for each of the outhauls. A bag below the boom winch collects the lazy ends which keeps the deck clear. The winch mount on the boom has always served well, and it seems it’d be more complicated to have it anywhere else, but I wonder if I am overlooking something?

Sounds like a good system. And good on you for realizing the issues of not having the main sheet to hand. Even if you don’t change that because of other reasons (perfectly valid) understanding the problem mitigates the dangers.

And no, I don’t think you are overlooking anything. Halyard and reefing winches moved aft over the years, I think, just because that looks good to those with less offshore experience who are the larger part of the market for new boats, not because it’s a more functional layout. Same reason most new boats have fat sterns, two cabins jammed under the cockpit and no deck accessible storage: it looks good at a boat show.

The evolution at Boreal is a good example of this phenomena at work. When the principles were designing a boat for themselves (the Mk1 boats) based on a lot of offshore miles, the winches were on the mast. Now that they must compete with other “expedition boats” the winches are in the cockpit.

Bonjour Messieurs,

I understand the friction issue, but for a shorthanded passage I am happy to have most of the lines coming back to the cockpit on the Mk2. This feels safer to me than having to move to the mast everytime that a sail must be reefed, and only the third reef should need intervention at the mast in the Mk2. This was one of my requirements for our boat and it was heard by JFD. Being novice, I may be in the wrong of course, and only time and experience will let me see the light on that topic. In which case, we could still electrify the other four smaller winches, or at least two of them, since at the current time, only the central main winch is electric on our boat. But this is a very interesting topic indeed, and I am glad that John provided his insights on it. Thank you so much.

Salutations de Montréal, Yan

My thoughts on why it may not in fact be safer to lead everything back are here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2020/09/11/second-level-thinking-about-offshore-voyaging-boats/

That you must go forward for the third reef, when the conditions will be most challenging, but will not be practising that regularly in easier conditions is much of why I worry about this trend.

That said, if one must have the lines lead aft, I think that the the Mk2 way is better than having them all jammed up under the dodger. Also, if you find you have a friction problem an Ewincher way solve it much more easily, and safer, than electrifying all winches: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/rigging-sails/ewincher-review/

This is part of why, in our re-jigging of Maverick V ‘s mainsail handling, we’re keeping all halyards and reefing at the mast. At some point, you’re going to have to go out on deck in rough stuff – so it’s probably best for that to be a routine, one that you practice so often that it’s easy and normal, rather than a rare special event.

The other reason is that, with kids often hanging out in the cockpit, I want as few loaded lines as possible that they have to watch for. It’s easy enough to teach them to stay clear of the traveller, mainsheet, and leeward jibsheet, but if there’s an 8-line jumble of spaghetti in the way, it’s harder for them to learn what’s loaded up (and thus must be avoided).

We tried running the main halyard back to the cockpit for a bit, and that caused more problems than it solved. Friction wasn’t an issue, but keeping control of the halyard while dropping or reefing the main became a 2-person job. It’s going back to its as-designed spot, a winch on the starboard cabin top beside the mast, this spring.

Our winches are mostly tail-it-yourself style, but we are replacing the #8 reefing winches and horn cleats on the boom with #18 Andersen self-tailers and Lewmar DC clutches so that Katy can grind those in by herself. I am quite impressed with the Andersen build quality and, at least around here, they are among the least expensive options.

Sounds smart to me. I have never used Andersen winches, but have heard good things for years.

Just a note about Barlow and Barient winches. I recently inherited a few, and recently had a very satisfactory experience with Hutton-Arco in Australia, which stocks parts for both brands. Their service was knowledgeable, friendly and fast.

moc.sehcniwnottuh@selaS

Another Barlow note: Rather than replace my big 1970’s non-tailing Barlow primaries, I converted them (about ten years ago) to self-tailing using the Winchmate kit. It took some fussing to get them to operate as smoothly as I wanted, but David Leitch was very helpful and we got there, and the $ savings were substantial. They have worked well. http://winchmate.com/

That’s good to hear, thanks.

I generally agree with the advice but am not sure I agree on the placement of primaries for all cockpit shapes. If you look at the second picture with Phyllis, it is extremely hard to effectively brace yourself fore and aft when kneeling on a cockpit seat (athwartships relative to the boat), especially when heeling. This means that there are 2 portions of the winch stroke which are really hard. The first is where the handle is furthest from your body, your leverage is not good, you are leaning significantly downhill and your body kinematics are not good at sideways motion. This one will always be true and the best solution is to be able to get over the top of the winch as you state. The second problem area is when needing to pull the handle back towards you, you often see people jerking backwards in awkward motions or trying to go back and forth in a different area using both speeds of the winch to avoid going around.

The best solution that I have found is to be able to stand behind the winch facing forwards. This gives you a good view of the sail but also lets you compensate for heel with your legs. Of course, the problem then becomes how do you actually create this standing area assuming you are not on a really big boat where everything can be done standing. On smaller boats, the best way that I know of is when a T shaped cockpit is employed and the winch is just before the cross in the T as far inboard as possible. It is quite easy to screw up this layout either with the sheet being in the way or interfering with the helm but done well I personally much prefer it. If you don’t have a cockpit that permits standing facing forward or aft at the primaries, then I think the suggested location is the best compromise. One other trick which I got from you but believe we differ on how much we like it is that a ratcheting winch handle can help if the winch is in the described location.

Of course if winching the primaries is the only goal and you can ignore other requirements, then a centralized setup like an IMOCA is best but that seems a bit extreme to me.

I agree, the best possible solution is to bring the winch into the cockpit where you can stand over it. The reason I did not go there is that, as you say, it’s just not practical on most existing cruising boats, which is our primary readership. (While I generally prefer the Mk 1 Boreals, I do like the primary winch positions on the Mk2.)

So given that and that I don’t like to see people getting into the habit of standing outside the cockpit, I would stick with my recommendation above, which I have found to work well. One thing that can screw that up is if the seat that one is kneeling on is too low.

Also, I kind of agree on the ratchet handle, in that while it has never worked well for me I think it might work well on a smaller boat with lower winch ratios. The problem on our boat is that since our primaries are a bit oversized and the ratio high, because of the size of the boat, it just takes too long with a ratchet handle, and conversely making a full circle and getting some momentum going works well.

And that brings up another point: I think that if people have trouble winching through a full circle in the position Phyllis is in, that’s an indicator that the winch is not powerful enough, not a problem induced by the position itself. Also, if they feel insecure, that may be because the coaming is too low and/or angled outboard too far. The latter is something I will write about more in a future piece that I have about half done.

My observation of cruising boat designs in the size range of interest leads me to believe that a decent percentage of them have T shaped cockpits but I don’t have any actual numbers to back that up. Of these, probably something like half would work well with winches setup for standing without major surgery, I have sailed on a few different boats doing this and I definitely liked it more but you usually can’t stand as outboard as is ideal so it is still not as good as a pedestal in the middle of the cockpit. I agree completely on not standing outside the cockpit. I am actually contemplating moving our primaries to exactly this position at the front of the T on our boat although it is not super high on the priority list. There are molded in spots for winches in the right spot, they were just not originally populated. Several owners have reported to the owners forum that they have made the change and it has been a big improvement. At the same time, I would update to winches with spring loaded self-tailers as the current winches are an appropriate ratio but push us into larger than needed sheets and those still want to fall out sometimes.

Your comments on speed and ratcheting handles got me thinking and I believe that one of the tricks is that humans do not have constant power output over a very wide range of speed. At low speed, our torque output does not increase as much as our speed dropped and at high speed, our torque output falls quite quickly until you just can’t spin any faster even at no torque. If we assume that winches are the same efficiency regardless of gear ratio, which is not a terrible assumption, then we want to be operating close to our peak power output point as the energy output of the system remains the same regardless. In the real world, it is very hard to do this because our leverage changes depending on where we are in the rotation and the load on the sheet changes depending on several factors. Ideally, the ratio would actually vary based on where you are in rotation but that becomes a very fancy winch and we should all just buy Ewinchers first as they solve this and other issues. The worst would obviously be a gear ratio that is not deep enough so you struggle to grind but going overly deep is not good either. Ergonomics will play a big part in the right winch gear ratio and also lead to a much less fatigued sailor if done right, I think you want to be just short of bogging down in the worst case scenario and then rely on the multiple speeds to help improve efficiency in lower load situations.

Good point about bringing the winches inboard on T shaped cockpits. I have been thinking a lot about this in relation to the Boreal 47.2 and am warming to it. No question that standing over a winch is best. I will write more on that soon.

Also interesting about our torque output. I think that explains well our different experience with ratcheting handles. Also it confirms my doubts about the new four speed winches we are seeing on some boats.

I hadn’t realized that there are now 4 speed winches available, interesting. I wonder what the ratios are? If you are only looking for max power or efficiency in an application with variable load, having more gears is always good as you can better fine tune speed and torque. However, the real world includes things like size, weight, cost, reliability, control logic, etc that don’t always make that a good idea. I think that the auto industry provides an interesting view into this, it used to be that everyone drove cars with 3 speed gearboxes and now many are 10 speed or even infinite within a band (CVT’s). It isn’t like they are only just learning the laws of physics, they are optimizing differently and there have been technical advances too. 3 speeds used to be considered a reasonable compromise, sure you were often not in the powerband of the engine or it was revved up real high when you didn’t need a lot of power but it got the job done cheaply. At the same time, the tractor trailers often had 12+ gears, sometimes in 2 sequential boxes, because they were extremely power limited so needed to be able to get the right ratio and with professional drivers, they could. As people demanded more performance from cars, transmissions crept up to be 4 or 5 speeds but didn’t go higher. From a sales standpoint, I suspect that it was due to users not really understanding the complex product and just focusing on how many horsepower it has. From a performance standpoint, engines had gotten to silly high power levels so the performance was fine and actually, they would have accelerated more slowly if they had to shift more as shifting is time consuming. The car companies have continued to push performance but also are now having to push efficiency and finally we have seen a very quick jump to approximately double the number of gears. This would not have made sense without also vast improvements in how quickly gears shift. Can you imagine going along efficiently at 60mph and 1500 rpm, pulling out to pass someone, mashing the throttle and waiting 3 seconds while it slowly shifted down through 2 gears so you were at 4000 rpm? Since this was not acceptable, they used to just have you cruise along at 3000 rpm burning more fuel and then you might drop 1 gear at max but often none. The setups now do a great job of allowing you to cruise along at a low and efficient rpm but then very quickly shift to a high rpm for power and the control logic is good enough that it doesn’t bother the user like slushboxes of old.

Applying this to sailboat winches, I am not sure exactly what is right. My guess is that the average user would not be particularly good about knowing when to change gears but the top users would be, just watch people ride a bike or drive a manual transmission car and see how many are not doing the right thing. Then there is the question of how gears are changed, if it is time consuming or tricky, that can negate all of the positives. If someone really wanted to nerd out on this, they could use a stationary excercise bike with a true power readout to map out speed versus power by simply varying the resistance.

One other lever that people have to pull is of course winch handle length, I am aware of 2 lengths but there may be more. If someone finds that they have slightly deeper of a ratio than they need, it could be that going to the shorter handle is better. Depending on the ratios, you may find that in the other gears, it is less optimal though so you need to optimize over the whole range of conditions. I suspect that America’s Cup teams have the data and optimize around this stuff but for everyone else, they use some rules of thumb and move on.

That’s really interesting and get’s me thinking about all sorts of winch related stuff including that I have noticed over the years that long duration winching, even at comparatively low loads, can be more exhausting than short duration at high load, even though similar amounts of work are getting done. The classic example is winching in the jib top furling line on MC feels more onerous than bringing in the lee sheet after a tack. That was the basis of my scepticism of 4 speed winches. But then again I have never tried one, so I could easily be wrong about that.

Thanks for your insights into human power development and ergonomics Eric; most interesting. Your observations seem to have many parallels to bicycling, where a dozen or so gears 10%-13% apart have been found optimal. It will be interesting to see how far down this path winch manufacturers will go. Will we see a 10-speed winch at some point? In the meantime, short and long handles for light & heavy jobs seems like a wonderful progressive step (simple & cheap.) While thinking about handles, the Ewincher offers another solution. E-bike makers are just cottoning onto the fact that they don’t need to provide so many gears so closely spaced. The e-assist makes up the difference between more widely-spaced gears. An Ewincher might prove a more reliable, fault tolerant, and redundant option than a future 4-10 speed winch.

I agree on Ewincher, See our in depth review: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/rigging-sails/ewincher-review/

Good article, John!

Our winch plan on Beatrix (44′ cutter) is very similar to your suggestions.

Part of selecting winches should be a consideration of maintenance issues. Servicing is a n important (and often neglected) task that should be done at once or twice a year.

When I re-winched about 20 years ago the sales guys at Fisheries Supply and I took apart an Anderson, a Harken, and a Lewmar to check the ease of servicing. Anderson was by far the easiest and Lewmar was the worst. We chose Harken, partly because they had a 15% off RRP program at the time which, combined with my 40% commercial discount, saved us a LOT of money, but most important was that they are good winches and Harken had a good customer service reputation.

For the primaries, we have 2 big 3-speed Harken 56.3ST winches. The insides resemble a Porsche transmission. ( I’m happy with the 3-speed winches but 2-speed would have been fine.) Kathy does all the servicing (she’s the “winch wench”) and she does it regularly. Unserviced winches eventually break teeth or become hard to use.

We also carry spare parts: all plastic components like the upper jaw, plus various washers, springs, pawls, and detent balls. Occasionally a tiny part is lost during servicing. The plastic upper jaws are all original. Where the winches are duplicates we don’t need a complete spares kit for each one.

Last, and not totally relevant to the topic, Sunbrella winch covers keep out dust and UV when not in use.

Cheers Jeff

I agree maintenance is important, although I have never found that the Lewmar winches were a problem, but then we have the older ones that I think were better in this regard.

That said, I don’t think a full maintenance is required every six months, or even once a year. Maybe on a race boat, but not on a cruising boat. My experience is that a full strip and clean every three to five years is fine.

If we did a full strip and clean every six months on MC, that would be fantastically onerous, given that it takes three full days for two of us to do all the winches on the boat properly.

A little bit of planning and practical geometry allowed us to put larger primaries (Lewmar 44s, rehabbed, freshwater-only “Ocean Wave” models from the ’90s) between our Andersen 40 primaries and our single speed Andersens we use for the staysail sheets. The heights differed enough so that the biggest winch, the Lewmar, clears the rest with the biggest winch handle. We can get right over the winches on the centerline standing in the footwell and all lines run fair through blocks from forward. The rest of the winches are at the mast (more Andersen 40s). The largest winch handle clears the Lewmar by 3 mm or about 1/8th of an inch.

If we need to winch the staysail sheet, it’s usually just one or two cranks, so the inability to do a full circle was no real compromise. We have no coamings on our rather strange boat, and so often attempt to think in non-obvious ways, such as “height of winch tops” to solve problems. We carry spares for both the Lewmars and the Andersens, both of which were easily obtainable and we strip down all winches for cleaning and related service (the occasional pawl replacement, mostly) every two seasons.

Hi Marc, this sounds like an interesting setup – do you have some photos available?

There are two photos in this blog post of interest…we had a busy month aboard. https://alchemy2009.blogspot.com/2019/07/good-grief-we-are-aboard.html

Thanks Marc! This is truly an unusual setup, but seems perfect for the functions intended. (hope you never have to use it to winch in a drogue…)

That’s actually what the aftmost Andersen 40s would handle, not that I anticipate that with enthusiasm as we’ll have to practice deploy the drogue in order to practice retrieving it! We are installing our drogue chainplates before launch in the next 60 days or so.

I find Pontos [now Karver] 4 speed winches a dream to use for the headsail primaries in my old age, and agree an Ewincher is perhaps the only satisfactory solution if the boat builder has stupidly put the mainsheet winch on the coach-house.

That’s interesting. I was sceptical about the 4 speed idea figuring that upping the ratio would just make the grinding job longer, albeit easier.

I truly love this site and it never fails to give me information I desperately need (even as it highlights more tasks to add to my already MASSIVE ‘to-do’ list!). While I realize that there are endless configurations of gear and systems, would it be possible to post a few “generic” evolutions for we somewhat crazy new-old boat owners? For example, “this is what I look for when inspecting and servicing my wheel steering system”. It certainly won’t look exactly like mine, but given that it performs the same function it should have useful similarities… and generate lots of horror story comments…

Hi Martin, Edson has maintenance manuals ( https://edsonmarine.com/product-tech-support-manuals-guides-and-maintenance-sheets/ ) that will give you most everything you need to inspect steering systems and to determine their current state and guide further care. My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Thanks for the kind words.

Although we don’t have an article specifically on checking steering systems we do have over 1150 articles. I would guess that over half of those are on some aspect of boat maintenance. They are also categorized and searchable (see top menu) so a lot of that is already done. And we have an online book specifically on maintenance: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/maintenance-refits/book-maintaining-cruising-boat/

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

How to Use Sailing Winches

- By Mike Lee

- Updated: June 14, 2013

Sailing winches are almost always taken for granted, yet these compact pieces of mechanical machinery are incredibly powerful. Even the winches on a 30- or 40-foot sailboat are capable of pulling 2 tons or more. The thing about winches is that they’re so reliable that most sailors rarely pay much attention to them—until something goes wrong. Using sailing winches correctly should always be a priority.

To understand the capability of winches, let’s crunch some numbers. Say your boat has a “number 42” primary winch, which is an industry standard. The “42” represents a 42:1 power ratio. If an average person applies 50 pounds of load using a 10-inch winch handle, the result will be 2,100 pounds of pull (42 x 50 = 2,100). That figure puts the power potential into suitable perspective. With this much power in play, you must consider whether you’re operating your winch safely. When it comes to sailing winches, the most common mistake is not having enough wraps around the drum to hold the line load safely. In most cases, three wraps just aren’t enough. With too few wraps, several issues can arise.

For example, say that you’re coming out of a tack with a little load on the new sheet. It’s still easy to grasp, so you lock it into the self-tailer. But as the wind freshens and the jib fills, the sheet load greatly exceeds what it was coming out of the tack. Now you want to bear away and ease the sheet. But with only three wraps on the drum, just releasing it from the self-tailer may suck your fingers into the winch. This is a very painful way to learn about winch loads.

Furthermore, beyond the personal hazard, higher loads and few wraps can also equal a damaged winch, as those greater sheet loads will be transferred to the self-tailing arm rather than to the drum. Replacing a bent or broken self-tailing arm is not an inexpensive proposition.

On the flip side, to err on the side of caution can also present problems. For instance, easing a sheet with too many wraps might result in an override that takes some time to unjam. The takeaway message here? There’s a fine line between too many and too few wraps. As is often the case in sailing, you can “feel” when it’s right. So pay attention to the loads on the winch, respect the powerful consequences, and wrap accordingly.

Sending someone up the mast? This requires even greater winch safety, as a life is literally in your hands. It’s a good idea to have an experienced sailor demonstrate for new crewmembers how to send someone aloft properly. Once again, it’s important to have a sufficient number of wraps to hold the person, yet not so many that the halyard overrides. Whenever possible, instead of trusting the self-tailer, always have a second person tailing the halyard. When lowering the mast climber back to the deck, ensure a smooth ride down by taking one or two wraps off the drum. You want to avoid bouncing and jerking the person the length of the spar.

Whenever you’re grinding a winch, if the load becomes excessive or extreme, simply stop cranking. This is especially important with winches powered electrically or hydraulically; with such winches, the operator can’t actually feel the increased tension. Take the time to observe the line. If it stops moving, this almost always means that something is jammed somewhere. A 2,100-pound load on a sheet that’s tangled around a deck hatch can quickly become a major problem if it isn’t immediately addressed.

With power winches, the loads are even greater. A small, electric winch motor can produce about 9 pounds of load, but because such engines spin so fast, the speed needs to be reduced. Enter a 24:1 reduction gear. However, the gear not only reduces the speed of the motor but also increases the torque—in this instance, to 216 pounds. Now multiply that by our previous 42:1 power ratio; suddenly, in theory, that little powered winch should be able to pull 9,072 pounds. (We say “in theory” because with a proper circuit breaker, the amperage draw should trip well before that load is reached. Also, the parts in a 42 winch are really designed to handle loads only produced by a sailor working a winch handle. If something does fail, it’s better if it’s a winch part and not anything more critical—like the mast.)

Of course, proper technique is only one part of winch safety. The other is making sure that they’re properly maintained. The little clicking noise you hear deep inside a working winch comes from the ratchet pawls. The pawls lock the drum in place to keep it from moving backward, and they essentially bear the entire load placed on a winch. When servicing a winch, it’s important to inspect the pawls to make sure they aren’t packed with gunk or cracked, which will cause them to stick in the socket. When that happens, there’s nothing to bear the load; essentially, it’s the same as trying to hold the jib sheet with a bare hand. At least once a season, check the pawls.

The winch’s mounting bolts also require periodic inspection. Over time, a surprising number of such bolts do loosen up, some to the point that they can be retightened by hand. Get in the habit of inspecting those bolts each spring, and while you’re at it, also test the deck section on which the winch is mounted. On older boats with cored decks, water may seep through the fastening holes and cause rot. In most cases, simply tapping the deck with a screwdriver tells the tale. A soft deck will make a different, easily distinguished sound from that made by a solid one. A rotten deck core won’t hold winch loads very long. Deck surgery is then required.

Remember: A single winch can generate huge loads, and these are often larger than most sailors realize. So always apply the correct number of wraps, avoid or correct jams, and keep up with basic maintenance. Treat your sailing winch with respect, and you’ll get plenty of trouble-free service from it.

Mike Lee is a marine-industry pro with over 25 years of technical and sailing experience.

- More: deck hardware , How To , seamanship

- More How To

How to Protect Your Spars from Corrosion

Sailing totem refit series: the forward head makeover, fatty goodlander: dealing with chafe while cruising, how to rig everything in your favor, one mile offshore with christian williams, winds of change.

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Using winches

Remember the old Charlton Heston movies in which sweaty, ragged sailors pulled in ropes, grunting "Heave, ho," like an ancient tug of war, while a barbaric foreman cracked a whip? Nowadays, you can use a winch to pull in that line (and leave your whip at home). You use winches, another way to provide mechanical advantage to adjust ropes under load, mainly on bigger boats , where loads on lines can get really heavy.

ajtiM^ Winches use a system of gears inside a round cylinder called a drum to give you the necessary pulling power. Always wrap the line clockwise around the drum, using more wraps as the load on the line increases. Put as many wraps around the drum as you need — the wraps provide the friction so you can hold a heavily loaded line in your hand.

The winch drum spins as you pull the rope wrapped around it if the rope isn't under load. But when the load builds (such as on a jib sheet when the sail fills during a tack), you need to turn the drum with a removable handle called a winch handle. This process is called grinding (and the folks who do it on big racing boats are called grinders).

While one person grinds, the other person pulls in (or tails) the line that feeds off the drum. One person can do both jobs, but doing so is less efficient. Some winches are self-tailing, meaning that they have a built-in mechanism that grips the line and holds it in place so that one person can grind without needing anyone to pull the rope. However, grinding is often a two-person process, as Figure 5-16 shows.