A Guide to Steering without a Rudder: Methods and Equipment Tested

Published on April 14th, 2014 by Editor -->

by Michael Keyworth I have been concerned for several years with the frequency of rudder loss and/or failure and the consequences of boats being lost or crew injured or lives lost. The purpose of the tests was to determine the best method and equipment to effectively steer the vessel to a safe port in the event of catastrophic rudder failure.

The goal was to utilize the equipment normally taken on the vessel on offshore passages or races. This guide is the result of multiple tests conducted in the fall of 2013 off of Newport, RI. The test vessel was a modified MK I Swan 44, Chasseur.

The overriding premise was; utilization of an efficient and controllable object to create drag and transmit to directional stability which results in the desired directional stability. It was my view that a drogue might be used to exert the appropriate drag. I further felt that a small drogue might provide the needed drag but not significantly impede the speed of the vessel.

Chasseur has been modified in the following relevant ways; the rudder skeg was removed and replaced with a modern spade rudder which is carbon fiber with a Carbon fiber shaft, the keel has been modified to a modern shape fin with a shoe, the mast is carbon fiber and 6 feet taller than original. For the purposes of the tests, the rudder was removed and the rudder port was blocked off.

I was familiar with and had onboard Chasseur a “Galerider” made by Hathaway, Reiser & Raymond of Stamford, Connecticut. I contacted Wes Oliver at Hathaway and he arranged to make several prototype drogues for the tests. We were equipped with: a 12inch diameter drogue with a 3 part bridle, a 12inch diameter drogue with a 4 part bridle, a 18 inch diameter drogue with a 4 part bridle, a 30 inch drogue with a 4 part bridle and a 36 inch drogue with a 4 part bridle.

The purpose of the test was to establish whether direction could be controlled under the following “underway” conditions using any of the drogues supplied: – With sail trim alone – Motoring using a drogue – Sailing upwind using a drogue – Sailing downwind using a drogue – Motorsailing using a drogue – Being towed using a drogue Size of drogue proved to be very important. The findings were definitive: – The two 12- inch drogues provided no directional stability. – The 18- inch drogue provided marginal control in winds under 10 knots – The 30- inch drogue was very effective in all conditions that were tested and resulted in approximately 1 knot reduction in boat speed. In wind conditions over 20 knots of windspeed a chain pennant needed to be added to reduce cavitation. – The 36- inch drogue worked similarly to the 30 inch drogue but affected boat speed by approximately1½ knots.

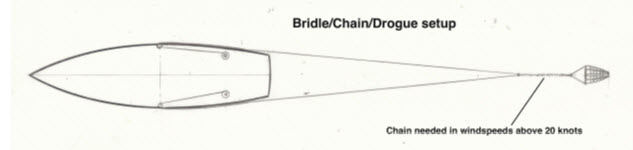

Rigging Two spinnaker sheets were used. I believe that spinnaker sheets are appropriate as they are generally sized based on length of boat. The sheets were led as two sides of a bridle (port and starboard) from amidships snatch blocks, thru amidships chock or similar and clipped into the swivel at the lead for the drogue. The tails were lead aft to the primaries in the cockpit. It is important to rig this so as to provoke the least amount of chafe as these lines will become your steering cables. We found that the leads need to be led to the axis of the keel as the boat will rotate on the keel. This point is probably somewhere near amidships.

Note : The afterguy block may be ideal for the bridle lead.

During rough and/or windy conditions it may be necessary to add weight to the drogue to keep it from cavitating. Using the concept of being limited to equipment that is already on board, we were able to use various lengths of chain attached to the swivel at the lead for the drogue. At the other end we effectively used a spare swivel shackle and attached one end to the forward end of chain and the other to the bridle from the boat. It is important to have swivels at both ends as the drogue will tend to rotate as it is pulled along. The bridle may get twisted up but this does not seem to affect the control. During our tests the length of “scope” of the bridle/drogue did not seem important. The nominal distance aft from the transom varied from 50 feet to 120 feet. It may be necessary to add scope in extreme conditions. I found that reference of the drogues position was valuable information. I whipped colored marks at 10 foot intervals on both spin sheet/bridle which gave a quick reference; this could be done with tape or magic marker.

Findings – Controlling direction with sail trim alone: Not Possible!!!

– Control direction while motoring using a drogue: This is the easiest scenario. A wide range of control is available. This can be done with only one person, easily. While testing we were able to execute multiple 360 degree turns with full control. Doing 5.5 knots a full 360 can be executed in 4-4 ½ boat lengths. While motoring, adjustments of 2-3 inches results in 5-10 degree course change.

– Controlling direction while sailing upwind using a drogue: The same principals apply except that there needs to be cooperation between the sail trimmers and the “helmsperson”(bridle trimmer). In this scenario the main must be up, even if reefed, the jib may be overlapping, but more control may be achieved with a non-overlapping jib. Tacking takes coordination but, once you get the hang of it, no problem– traveler up, back the jib and come on to the new tack. We were able to achieve 30-35 degrees apparent sail angle. In large seas wider angles should be expected.

– Controlling direction while sailing downwind using a drogue: When the wind is aft of 90 degrees apparent it is necessary to take the mainsail down and sail under Jib alone. It will be necessary to have an attentive jib trimmer in addition to a helmsperson on the drogue controls. The size of the jib will have to be factored in based on wind and sea conditions. We also found that the deeper the angle the harder it was to have fine control of direction. Jibing is pretty straightforward by easing the jib and rotating the drogue.

– Controlling direction while motorsailing using a drogue: The same principals apply as in sections on upwind and downwind sailing.

– Controlling direction while being towed using a drogue: This test, I felt was important because most successful results of rudder loss has a component of a tow of great and small distances to a safe harbor. In this situation we were towed by a 27’ Protector with two 250 HP outboards. A towing bridle was made up on Chasseur and attached to the tow line from the Protector. At 3 Knots the bow was swinging from port to starboard to the end of the tether. At 4 knots it was very difficult to stand on the foredeck. We deployed the 30 inch drogue as rigged for sailing and motoring. The results were immediate. Towing at 7 knots was comfortable and straight, requiring very little input from the helmsperson.

This is an important finding as it suggests that a drogue should be carried at all times so that assistance can be rendered safely, even inshore.

Additional Findings/ FAQs

– If you lose your rudder: First confirm that the rudder port is not leaking- if it is you must first deal with the flooding issue. Once the flooding issue is stabilized move on to the next step of getting home or assistance.

– Communicate with Race Officials if you are racing and/or with those onshore who will worry about your situation.

– Communicate with vessels nearby if in need of immediate help away from a lee shore or collision avoidance in shipping lanes.

– Choose your safe harbor destination based on wind direction predictions, ease of access, proximity, repair facilities, etc. Do not feel that you need to end at the original destination port.

– If you lose your rudder, it is likely that you either hit a submerged object or that the conditions were severe. Remember that you have time. Relax, storms don’t usually last more than a couple of days. Deploy your drogue or sea anchor and get some rest.

– Each time that we went testing we learned something new. Don’t be afraid to try something that you think might help, i.e. longer scope, move lead of bridle forward or aft, larger/smaller jib, reef/no reef, etc.

– An unanswered question is how a drogue will work with different types/styles and underbodies than Chasseur. My personal view is that a drogue will be an effective tool to have on any type of boat and its deployment can be adapted to the type of vessel that uses it. – Offshore you will have room to maneuver. Take your time and don’t stress about steering an accurate course.

– The engine is your friend. You will find that using engine power will provide the greatest degree of control- speed and direction. Use the engine to deploy sails, to get rest, or to retrieve the drogue- retrieval is easiest when the boat is stopped. Be careful to not tangle the bridle in the prop. This was never a problem during our trials. This was probably because; towards the end of trials we used a 5 foot chain pennant to help the drogue from cavitating. The chain component is an important one. I chose the use of chain to weight the drogue because ISAF Offshore Prescriptions require that an anchor with appropriate ground tackle be carried, so it need not be carried as additional gear. Others venturing offshore tend to take ample ground tackle to accommodate the use for other purposes. On a practical matter, I think that it makes sense to have different lengths of chain for required circumstances. It also makes sense that a longer chain can be made shorter using the rig cut away tools as required by the rule. A shorter chain can be made longer using shackles to join shorter lengths.

– How heavy is the Galerider? A standard 30- inch drogue weighs in at 9 pounds and is stored in a bag that is 15 inches in diameter and 5 inches thick. The standard 36- inch drogue weighs 13.2 pounds and stores in a bag that is 18 inches in diameter and 4 inches thick.

– One of the difficulties that you will face to determine where the helmsperson is stationed and has access to heading or a compass. Something that you may want to consider, as you equip for an offshore passage is the purchase of a backup compass which can be remotely mounted. Boats equipped with modern electronic packages may have the option of display of heading for both helmsperson and trimmer/s.

– It would be prudent for any offshore sailor to practice the deployment of a drogue for speed reduction sailing downwind in large seas and to rig and use as a means of steering. This would help to identify the gear necessary to deploy and provide a ready plan to implement if necessary.

– The transition from drogue to drogue steering or vise versa may be easier than you think.

– A trick that we learned is that you can cleat off one of the bridle lines and have control with the other. If you were to cleat off the port bridle line a turn to port would result from easing the starboard bridle and a subsequent change to starboard would result from trimming the starboard bridle. This lazy mans approach gives the helmsperson more flexibility and physical relief.

– What I learned from the extensive testing is that you can achieve a great deal of control using a drogue. I would bet that if any boat is able to sail 100+ miles without a rudder to a safe port, the crew will want to take a victory lap around the harbor to “show off” the newfound skill and seamanship ability.

One last thought. Having sailed over 150,000 miles at sea I have seen many things and have been able to overcome all sorts of adverse conditions, I still have many concerns and reservations. One concern is that of rudder loss and how to deal with that possibility. This test should help all who go to sea with that possibility. The other concern that haunts me each time I go to sea is the amount of floating debris and other objects that may affect the ability of even the most seamanlike sailor to safely passage from place to place. The possibility of being holed or sunk from collisions with floating debris is real. Most of the stories I have heard about boats at sea that have become rudderless have resulted in the abandonment of those vessels. These abandoned vessels represent a threat to those fellow sailors who put to sea and put them unnecessarily at risk. Michael Keyworth is Vice President and General Manager of Brewer Cove Haven Marina in Barrington, RI.

Tags: education , Safety

Related Posts

Testing the scoring programs →

Programming to improve with each race →

Crocodile – 1, Sunfish sailor – 0 →

VIDEO: DragonFlite 95 boat tuning clinic →

© 2024 Scuttlebutt Sailing News. Inbox Communications, Inc. All Rights Reserved. made by VSSL Agency .

- Privacy Statement

- Advertise With Us

Get Your Sailing News Fix!

Your download by email.

- Your Name...

- Your Email... *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

How to Sell Your Boat

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Open Transom Pros and Cons

Leaping Into Lithium

The Importance of Sea State in Weather Planning

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

When Should We Retire Dyneema Stays and Running Rigging?

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

How Dangerous is Your Shore Power?

DIY survey of boat solar and wind turbine systems

What’s Involved in Setting Up a Lithium Battery System?

The Scraper-only Approach to Bottom Paint Removal

Can You Recoat Dyneema?

Gonytia Hot Knife Proves its Mettle

Where Winches Dare to Go

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Rhumb Lines: Livin’ the Wharf Rat Life

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Safer Sailing: Add Leg Loops to Your Harness

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Safety & Seamanship

Sailing Without a Rudder

Drogues offset helm to get you home again..

Loss of steering may well be the most common cause of rescue for boats sailing offshore, but the problem is even more common inshore where there is more debris to hit. An emergency rudder is always possible, but for most of us, extra gear to rig, cost, and strength concerns most often render the option impractical. Wrestling an emergency rudder into position will be physical and possibly dangerous in rough conditions. In the case of a catamaran it is simple to disconnect a rudder that is jammed straight, but what if it is jammed hard over, as in the loss of the Alpha 42 Catamaran Be Good Too in 2014? Tests have been published using drogues for steering with the rudder either removed or locked in position, showing that in moderate weather even sailing to windward is practical as long as sails were adjusted in concert and the drogue position was adjustable. Our questions go further. What if the rudder has jammed an angle? Are all drogues appropriate for this purpose? How do you choose the best size?

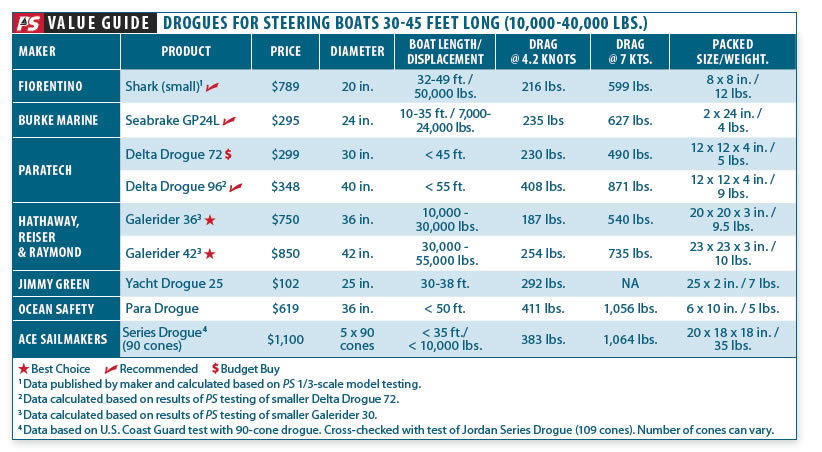

Our goal was not only to test rigging methods and drogues, but also to quantify how it sailed under drogue steering control. What rigging works best, what size drogue is required, what courses can we sail, how stable are they, and how quickly will we get home? In H ow Much Drag? ( Practical Sailor September 2016) we collected data for a range of commercial drogues. That information will help you translate out findings into a steering drogue that will work for your boat.

What We Tested

For steering, a relatively low-drag device is required. While parachute-type sea anchors and high-resistance or stopping drogues may be good for surviving a severe storm, they arent useful for getting to port with no steering. As we will learn, if the drogue produces too little drag, we can’t control the boat in all circumstances; too much drag slows us down and prevents progress to windward. Thus, we tested the Seabrake GP24L, Galerider 30, Delta Drogue 72, and a towed warp.

We tested using a 32-foot PDQ catamaran with the rudders still in place, either locked straight or at 60 percent to one side to simulate a single rudder jammed hard-over. Each of these simulates an actual occurrence, and even on monohulls, bent and jammed rudders are more common than lost rudders. Of course, losing the rudder entirely presents a slightly different case, since the rudder provides some portion of the lateral plane as well as steering control. Much depends on the underwater profile of the boat and the sail plan, so you will need to practice and amend our findings to fit your boat.

How We Tested

We deployed each device on 100 feet of polyester double braid rope, weighted with 8 feet of 5/16-inch chain, and towed them at two speeds (3 knots and about 4-5 knots) to develop a speed-versus-drag relationship.

We then deployed each device from our test boat using a bridle formed by a pair of spinnaker sheets (see Improve Steering Efficiency, on right) and sailed a variety of courses in a variety of wind speeds up to 30 knots sustained in semi-protected waters, building a rough speed polar for each device. We also compared performance with different the bridle attachment points and rode lengths. For initial testing we deployed the drogues from a bridle consisting of spinnaker sheets led to turning blocks at the toe rail about 8 feet forward of the transom, varying both bridle position and sail trim until the best speed and course were attained. We then sailed each course for at least 10 minutes, collecting averages and judging stability. The result is an overall picture of how the boat sailed around the course with each drogue. We then practiced with several of the drogues, deploying them on longer rodes in stronger conditions, using both the genoa sheet bridle and a bridle formed by deploying with a single line from one winch, and then deflecting it to one side using a snatch block and pendant led to a winch on the other side.

Drogue Selection

How to pick the best size drogue for emergency steering? In snubber testing we found our 34-foot catamaran test boat to be roughly equivalent to the ABYC 40-foot monohull in terms of windage, which gave a lunch hook anchor load of 300 pounds. Our recommendations for winds up to 20 knots is to pick a drogue that produces about 60 percent of the ABYC lunch hook load when towed at 4.2 knots. For stronger conditions, up to gale force, go up 100 percent of the AYBC lunch hook load; the larger size can be de-powered by using on very short scope, within limits.

Following this logic and our on-water experience, the Seabrake 24 and Delta Drogue 72 were well sized for our 34-foot test boat in moderate to fresh conditions. The Galerider 30 was wonderfully smooth and fun to use, but it was over powered in winds above 15 knots (the Galerider 36 is the correct size for the test boat).

Since all products were tested in moderate conditions on a single boat (34-foot catamaran), our recommendations should be adjusted to reflect the boat you have and conditions you anticipate. In How Much Drag is a Drogue? we presented drag data and more detailed reviews.

Delta Drogue 72, Paratech Engineering

Based on an equilateral triangle of fabric, the Delta Drogue 72 is dimensionally similar to the other units in the test (the size designation is related to the side of the triangle and not the inflated diameter). It did have the occasional bad habit of skipping out of the water when overloaded at short scope, but not fully, and it very quickly re-engaged, always before any effect on course was noticed. The elegantly simple design is functional, well-proven, and strong.

Bottom line: Though a simple cone drogue may be cheaper, this represents the Best Buy in a real offshore drogue.

Galerider 30, Hathaway, Reiser & Raymond

Providing by far the most consistent drag at varying rode length and in waves, it was the tester favorite. While other drogues produced wildly fluctuating drag forces both under water and when near the surface, the Galerider was remarkably stable under water and by far the least affected by surfacing. Our sample drogue was a 30-inch diameter size, and a 36-inch diameter was prescribed for our test boat. As a result, the we had trouble maintaining control with the undersized drogue in higher wind speeds. While added weight is not required for speed limiting use in storms, Galerider does recommend a short length of chain for steering use, primarily to allow it to be pulled very close behind the boat and still stay in the water. Considering the long service history of the unit (over 1000 units over 20 years), durability has generally been very good.

Bottom line: In all but the windiest conditions, the Galerider excelled. We have no doubt a larger diameter would have fared better. It is our Best Choice for emergency steering.

Seabrake 24

Although a little too large for light wind emergency steering, the extra drag was appreciated with the wind over 20 knots and when the rudder was locked to one side. Compared to the Galerider it was less stable when towed on extremely short rode to reduce drag, but still functional and quite stable with 50-100 feet of rode. Seabrake: The reduction in speed near beam reach is due to dropping the mainsail.

Below 10 knots we were able to fly the chute at angles below 150 degrees true. Speeds in stronger winds include wave effects but not surfing. The Seabrake may have been faster in light winds if we had hauled it to very short scope, but that was not what we were testing. We did observe this, however; drogues pulled in close were faster, but less stable. We believe the Gale Rider would be more stable, since it does not skip.

Bottom line: Recommended for larger boats and for stronger conditions in smaller boats.

Small Shark, Fiorentino

Perhaps the easiest to deploy, it is compact for the drag produced, packs very small, does not require chain in front of the attachment (it does require a tail weight, typically a small mushroom anchor), and is easiest to get in the water. The Small Shark, with the mushroom anchor at the base, gets strong marks for ease of deployment; just heave it off the back.

Bottom line: Durability, easy deployment, and small size earn a Recommended rating.

Warps and Chain

Boats have sailed impressive distances with rope, chain, anchors, and fenders linked together to make a jury-rigged drogue. We tested just two 100-foot x -inch lines with 30 feet of 3/8-inch chain between them.

Bottom line: Not enough drag to do anything worthwhile unless a lot more stuff is added.

Conclusions

We always thought drogues were only for ocean passages and dangerous storms, until we struck a log and felt the helplessness of no steering and the closeness of a lee shore. We learned that loss of steering is a coastal sailing risk as well. Fortunately, a drogue and the knowledge to use it can restore a useful level of control in minutes.

Steering is more limited and laborious than plain sailing, and you wont point as high, but you can stabilize the boat to hold a course on most points of sail. With even low engine RPMs as a boost, you can sail most courses in moderate weather. Drogues can also temporarily replace a failed autohelm on downwind courses, although speeds are reduced; setting an retrieving a drogue in moderate conditions for this purpose is not difficult, and could be well worth the effort to gain a rest period. We were happy with spinnaker sheets for controls, though we suspect a turning block location at the point of maximum beam would better suit monohulls.

We strongly suggest practicing with the boat you have; you may find different rigging works better and re-rigging once the drogue is in the water can be very difficult. Our testing was limited to sustained winds 30-35 knots and wont pretend to know how emergency steering works beyond our experience. However, steering problems can also occur in moderate conditions, either the result of a collision, or in the aftermath of a storm, where a boat that has otherwise come through with minimal damage is prevented from heading to shore by one damaged appendage. We think steering drogues address these problems, and thus make sense for all sailors.

- Ideal Drogue setup will require experiments

The above table lists drogues recommended by their manufacturers for boats that generally fit in the 30- to 45-foot range. This is an estimated size, and the broad range of boats in this category—stretching between a Catalina 30 to a William Garden Vagabond 47—illustrates the importance of consulting manufacturers and researching other reports when matching a drogue size to a boat. PS tested five of the above drogues. The source of other data is noted in the table.

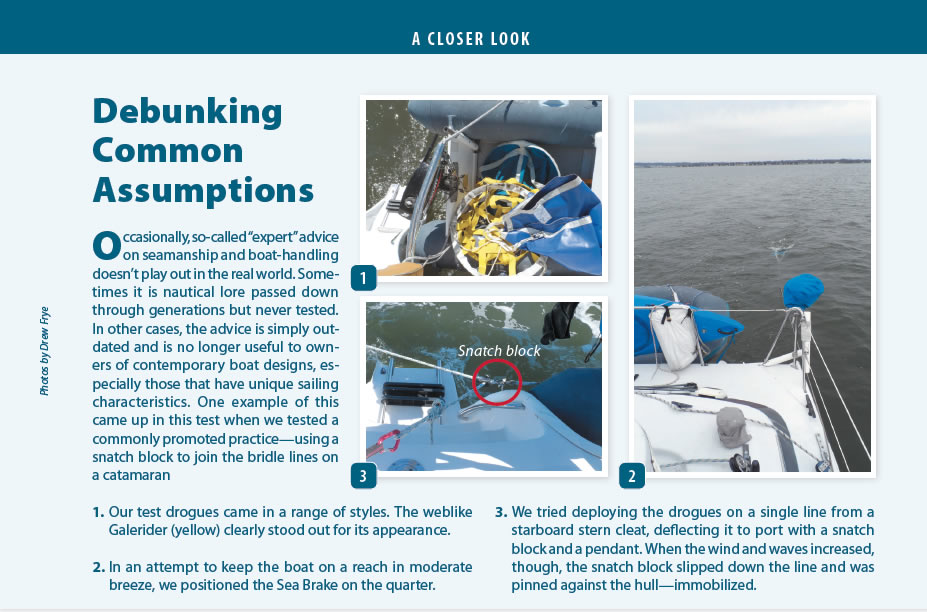

Occasionally, so-called “expert” advice on seamanship and boat-handling doesn’t play out in the real world. Sometimes it is nautical lore passed down through generations but never tested. In other cases, the advice is simply outdated and is no longer useful to owners of contemporary boat designs, especially those that have unique sailing characteristics. One example of this came up in this test when we tested a commonly promoted practice—using a snatch block to join the bridle lines on a catamaran

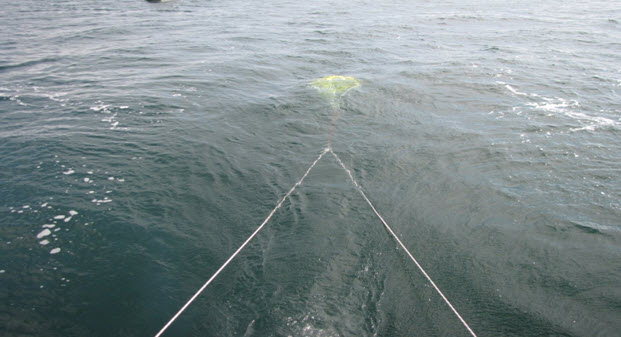

- Our test drogues came in a range of styles. The weblike Galerider (yellow) clearly stood out for its appearance.

- In an attempt to keep the boat on a reach in moderate breeze, we positioned the Sea Brake on the quarter.

- We tried deploying the drogues on a single line from a starboard stern cleat, deflecting it to port with a snatch block and a pendant. When the wind and waves increased, though, the snatch block slipped down the line and was pinned against the hull—immobilized.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

How Can I Keep My Kids Safe Onboard?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

Island Packet 370: What You Should Know | Boat Review

How To Make Starlink Better On Your Boat | Interview

Catalina 380: What You Should Know | Boat Review

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

Can You Sail Without A Rudder?

Before you embark on any sailing trip, be it a short or longer one, you always triple-check that all parts of the vessel are secure. You would hate to be without any of the components, after all, yet sometimes, that’s just what happens. If your sailboat loses its rudder, what do you do? Can you still sail?

Yes, it’s possible to sail without a rudder, a part of your boat that helps you steer. To manage turns, you need to rely more on the heel and sail trim of your sailboat as well as the boat’s weight. You also want to work with the wind, as it can keep you moving in the right direction.

It’s not uncommon to lose your rudder on a sailboat, and many sailors have safely navigated to their destination without one. In this article, we’ll explain more about what the rudder does, why yours may disappear, and how to sail sans rudder. You won’t want to miss it.

What Is a Rudder?

Just to ensure we’re on the same page, let’s start by defining your sailboat’s rudder. This is a steering control surface found on sailboats as well as submarines, other boats, and ships. Aircraft and hovercraft have rudders as well.

Rudders feature a blade-like edge, and they’re taller than they are wider. You can find a rudder on your sailboat off to one side, typically by the skeg. This rudder can be inboard or outboard. A rudder that’s inboard hangs from the boat’s skeg or keel. Inboard rudders go fully under the hull. In this position, they can attach to the boat’s steering mechanism via a rudder post. This post goes from the hull up to the deck and through the cockpit.

If you do a lot of off-shore sailing, an inbound rudder is your best bet, as it may be able to withstand these conditions better.

An outbound rudder has a much simpler setup, as it hangs as well, but this time from either the transom or the stern.

Generally, if a rudder has fin keels that are small, it handles more quickly and efficiently than a bigger one would.

How Do Rudders Work?

Now that you understand the basics of sailboat rudders, let’s dive a little deeper into the topic by describing how rudders themselves work.

As we mentioned in the intro, when a sailboat wants to steer, it relies in part on the rudder. As water flows towards the boat per the direction you’re going, the rudder pushes the water away. You can turn a rudder as well, causing one side of it to strike water at a weaker force and the other side at a stronger force. The rudder follows whichever side has less pressure.

Your sailboat’s rudder moves in conjunction with the stern, thus effectively turning your boat. If your boat is 30 feet or shorter in length, then a tiller may be included with the rudder. This will move the rudder as you turn or steer.

These tillers are aluminum or wood and sit atop the rudder. The reason a tiller is added to your setup is to provide leverage to the rudder. Now, this smaller rudder (to accommodate for the smaller boat) can still move if water pressure gets high, allowing you to turn.

Why Do Rudders Fall Off?

While rudders are a key component to regular sailing, they don’t necessarily stick with your boat forever. They can fall off while sailing and you often won’t even notice. It’s only when you get back to shore that you realize you’re rudder-less, and there’s no way to go back and recover it. You don’t even know where the rudder fell off.

What causes the rudder to vanish? There are all sorts of reasons this happens. In some instances, saltwater can degrade the quality of the rudder until it’s so brittle it can’t stay on your boat. The high water pressure can also sometimes knock the rudder right off.

If your rudder isn’t secure for any reason, then you can lose it quite easily. The same is true if it’s broken or damaged. Sometimes the stocks of the rudder corrode, weakening the entire structure. If you race your sailboat, you’re at risk of coming back without a rudder as well. Also, hitting something submerged in the water can smack your rudder off your sailboat.

What to Do If You Lose a Rudder

Okay, so your rudder is gone. You’re not sure how and when it happened, but you have no rudder, and that’s what’s most important.

There’s no need to call off your next sailing expedition or even head to shore if you’re already on the water. It is possible to sail without a rudder, which we’ll describe in much more detail in the next section.

You can also rely on your drogue in such a situation. A drogue is a type of boat device on a line that connects to the stern. If stormy conditions are in your future, then a drogue is very useful to have, since it can control your speed so you don’t go racing into inclement conditions. In strong waves, a drogue is also your best friend, as it protects your hull against the waves. We’ll talk later about how to use a drogue, so keep reading.

It’s important not to panic without a rudder, even if you do find yourself in stormy weather. Instead, closely study the information presented in these next two sections. Keep it in mind each time you set sail. After all, acting deftly and confidently can get you out of a dangerous situation faster than freaking out.

How to Sail Without a Rudder

Turning your sailboat without your rudder may seem impossible, but it’s anything but. Instead of being more reliant on the rudder, you want to use the heel of your sailboat, its trim, and the weight of your boat to help you navigate.

It’s ideal if two of your sails are in functioning shape (such as after a storm) so you can get upwind. By putting downward pressure on the stern, you will move upwards, and by putting downward pressure on the bow, the jib allows you to sail downwards, also known as falling off. Pulling in the mainsail and releasing pressure on the jib can control this falling off if need be.

Depending on the weight of your boat, its aft and fore angles or trim and side angle or heel changes. Since your sailboat has a natural curvature, based on the curved direction of the hull, you can guide your heel and thus your turn.

For example, if you wanted to head downwind, many sailors will heel the sailboat so it’s windward. This creates balance in the sail without the need to round up or head upward.

Watch the aft and fore trim as well, especially without a rudder. Adding too much stern weight can off-center the sail’s effort, making it go forward and causing you to round up. The bow shouldn’t have so much weight that your stern rises out of the water, as this will make your sailboat fall off.

If all this sounds complicated, that’s okay. Like with any sailing technique, it takes time, practice, and close knowledge of your boat to get a feel for sailing without a rudder. Luckily, this isn’t one of these scenarios that have to remain an emergency only. You can always pop your rudder off on a sunny, pristine day and practice sailing without it. This way, you know that should you ever lose your rudder for real, you’d be ready.

How to Use a Drogue

We said we’d get back to how to use a drogue, so let’s wrap up with that now. As discussed before, a drogue can act sort of like an anchor when it’s deployed. You’d want both sides of the drogue’s line attached to the stern, and then you could release it.

When the drogue is in the water, it allows the stern side of the sailboat to have more drag. This means a breach cannot occur, or the transom cannot exceed the bow. With your drogue, you can also maintain stability and direction, going straight or doing other steering.

To trim your boat with a drogue, connect a bridle to either side of the starboard and cleats port. Then, take one of the bridles and shorten it. This will turn your sailboat.

Not only does having a drogue help if your rudder falls off, but there are other scenarios where it comes in handy. For instance, if your boat runs out of gas in the middle of the water, the drogue becomes a makeshift steering system for emergencies.

Again, rather than wait until you’re in a truly dicey situation to test your knowledge of how to use your drogue, why not do a practice run in clear, open waters? With your rudder off and your steering skills down pat, deploy your drogue and see how well you can use it. Did you have a hard time steering with the drogue? If so, keep practicing. Should you ever need to use the drogue, you’ll know just what you’re doing.

Conclusion

The rudder is a part of your sailboat that allows for easier steering. Rudders come off the boat all the time, either because of age, poor condition, turbulent waters, or collisions with undersea debris.

If your rudder is gone, don’t panic. You can still steer without one, although it requires you to know about boat angles and using the wind to your advantage. You should also rely on your drogue, a type of anchor-like appendage that controls speed when deployed.

Now, no matter what life throws at you on your sailboat, you’ll be prepared. Happy sailing!

I am the owner of sailoradvice. I live in Birmingham, UK and love to sail with my wife and three boys throughout the year.

Recent Posts

How To Sail From The Great Lakes To The Ocean

It’s a feat in and of itself to sail to the Great Lakes. Now you want to take it one step further and reach the ocean, notably, the Atlantic Ocean. How do you chart a sailing course to get to the...

Can You Sail from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico by Boat?

You have years of boating experience and consider yourself quite an accomplished sailor. Lately, you’ve been interested in challenging yourself and traveling greater distances than ever before. If...

- Cruising Compass Media Advertising & Rates

- Blue Water Sailing

- Multihulls Today

- Subscribe Today

Steering Without a Rudder

In modern cruising and racing sailboats with fin keels and spade rudders, the most vulnerable part of the whole boat is the rudder. Every year during the fall and spring migration seasons when hundreds of boats sail offshore between winter and summer cruising grounds, a few have rudder problems. Collisions with submerged containers or a whale, can do serious damage to a spade rudder. Getting tangled in a drift net or other fishing gear can cause a rudder to fail. Very occasionally rudder posts break off between the rudder and the hull; this can be caused by work-hardening in stainless steel or aluminum posts or a poor laminate in a composite post. Whatever the circumstances, if you find yourself without your rudder with many miles still to sail, you don’t have to call for help because the boat can still be sailed and steered. But, you have to be prepared.

Veteran offshore sailor, skipper and professional Michael Keyworth took it upon himself in 2013 to figure out how to prepare a sailboat to be steered without a rudder. The old ideas of fashioning a rudder with a spinnaker pole and a table leaf really doesn’t work for any length of time. What has worked in the past is towing a drogue of some kind behind the boat. But this concept has never been really effective. Keyworth removed the rudder from his Swann 44 Chasseur and set about doing sea trials with all sorts of different jury-rigged steering systems. What he found was there are several key elements to setting up an effective drogue steering system. First, you need the right type and size drogue. He found that a 30-inch Gale Rider gave the best connection to the water while reducing speed by only a knot. Second, the control lines on port and starboard should not be run directly to winches in the aft cockpit. Instead, the control lines should be run to snatch blocks fixed to the amidships cleats on the side decks and then aft to the cockpit winches. These cleats are generally positioned close to the boat’s center of gravity and to the center of lateral resistance in the keel. In other words, without a rudder aft, the boat’s pivot point is the keel. Third, in winds over 20 knots, a length of chain needs to be added to the Gale Rider’s bridle to keep the drogue well immersed in water.

With this rig, Keyworth found he could control Chasseur on all point of sail and could even tack without turning on the engine by simply trimming the control lines port and starboard. He wrote up his findings with all of his observations and recommendations in a comprehensive report, and you can find it on the Newport to Bermuda Race’s website. If you truly want to be self-sufficient and self-reliant when sailing offshore, knowing how to sail your boat without the rudder is an important, even life saving skill. Read the full report here.

Sandy Parks

You might also like.

- She Asked, How Hard Can It Be? Boys Do It

The Discover Boating Miami International Boat Show Opens Next Week

All New Beneteau Oceanis 37.1 Family Cruiser for 2024

Read the Summer-Fall Edition of Blue Water Sailing

Read the fall 2023 edition of blue water sailing, recent posts.

- Survey of the Week

- Introducing the New Twin-Keel, Deck Saloon Sirius 40DS

Please Visit Our Sponsor’s Webpages

- Media Advertising & Rates

Published by Blue Water Sailing Media, a division of Day Communications, Inc., Middletown, RI

Publisher & Editor: George Day

Blue Water Sailing Media publishes Blue Water Sailing magazine, Multihulls Today and other titles.

Cruising Compass Advertising Sales:

George Day, Newport, RI [email protected] 401-847-7612

- New 2024 Bavaria C50 Tour with Yacht Broker Ian Van Tuyl

© 2014 Blue Water Media. All rights reserved. | Admin

Rudderless Drill

Reprinted from “Fundamentals of Sailing, Cruising, & Racing” by Steve Colgate; published by W.W. Norton & Co.

Another drill one hopes never to have to use is sailing without a rudder. Though you may sail 20 years without losing your rudder at sea, it could happen your first time out. You can control the direction of the boat by changing the efficiency of the sails fore and aft. By luffing the jib and trimming the main, we create weather helm and the boat turns into the wind. By luffing the main and flattening the jib, the wind pushes the bow to leeward – in other words, lee helm. To practice this, trim your jib reasonably flat and ease your mainsail until the boat is balanced and sails straight ahead when the helm is released. Then change your course by trimming the main to head up and pushing the boom out to fall off. When the bow starts swinging in one direction, you must immediately begin the opposite procedures to counteract the swing.

In order to tack, free the jib sheets and trim in the mainsail hard and fast. As soon as the boat is past head-to-wind, trim the jib and ease the main to force the bow down. If necessary, back the jib.

Jibing is much more difficult to do without the rudder because the mainsail causes the boat to turn toward the wind when running. To try it, ease the main completely, making sure the boom vang is also loose, and back the jib to windward. As you fall off to a run, move all the crew to the windward side of the boat and hike out. By heeling the boat to weather, lee helm should be created. Just as a bow wave on the lee side pushes a heeling boat to weather, a bow wave on the windward side (caused by healing the boat to windward) pushes the bow to leeward. In this case, we are using crew weight to help a rudderless jibe, but at other times crew members hike out to weather, not only when closehauled, but on reaches and runs to reduce weather helm.

If the breeze is very light, we can make minor adjustments to the helm by moving the crew weight forward and aft. With the boat balanced as described above, move the crew well forward toward the bow. The boat will head into the wind as the curve of the bow bites more deeply into the water. By moving the crew to the stern, the bow will fall off to leeward.

We hope you found our advice on how to sail without a rudder helpful. Happy Sailing from Steve Colgate , founder of Offshore Sailing School!

Recent News

National learn to sail month – aboard the leopard 45 with offshore sailing school, offshore sailing school controller dana matthews promoted to evp, chief financial officer at company, to thailand…and back – what an adventure.

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

- Uncategorized

Ship Without a Rudder

- By Herb McCormick

- Updated: July 5, 2005

It’d been a bouncy, wet, exhilarating 13 hours since we’d answered the starting gun off Fort Lauderdale last February 4 to begin the roughly 800-mile race to Jamaica in the 2005 edition of the biennial Pineapple Cup (formerly known as the Miami-Montego Bay Race). Aboard Serengeti, an exquisite 60-foot sloop owned and skippered by veteran sailor Chad Weiss and designed by naval architect Bill Tripp, things seemed to be shaping up nicely.

We’d bolted across the Gulf Stream in bumpy but blistering fashion and had already put the Bahamian waypoints of Great Isaac and the Berry Islands astern. Now all we had to do was round the north end of Eleuthera island, hoist one of Serengeti’s big kites, and ride the steady, 20-knot-plus northerly south with all dispatch. Forecasters predicted the potential record-setting conditions would hold for several days. Serengeti was sitting pretty.

It took but a split second for it all to unravel.

Regular Serengeti crewmember Joe Nanartowich was at one of the yacht’s twin wheels when he heard “a little ching.” The boat rounded up instantly, and instinctively, Nanartowich swung the helm down hard to correct his course. But the spokes spun round and round like TV’s Wheel of Fortune, and Serengeti’s ensuing “auto-tack” and wipeout were nothing less than spectacular.

In every sailor’s life there’s a first time for everything, and I count myself extremely fortunate that my first lost rudder at sea was experienced aboard a well-equipped oceangoing sailboat with a highly skilled team ready for anything. So, despite the fact that our promising race was finished, not all our luck was bad. Indeed, the rudder vanished in the deep, unobstructed waters of Northeast Providence Channel, not along the lee shore of a coral-fringed island (which would have been the case a couple of hours later). And among the crew was Bill Tripp himself, ready and willing to tackle the question any sailor in such a predicament would ask: “Now what in the world would the designer do?”

But I’m getting ahead of the story.

Fast Break from Florida Built in New Zealand at Marten Marine of a composite blend of aramid and E-glass over a PVC core, Serengeti is a high-tech sailboat sporting a lifting keel and carbon rig, items that have served her well in such offshore races as Newport-Bermuda. But she’s also a true dual-purpose boat, with a handsome, functional interior laid out for the family cruising and occasional living aboard that owner Weiss also enjoys.

When we left Florida, however, the boat was in full racing mode, her saloon stacked end to end with spinnakers and headsails, her crew a dozen strong. With temperatures in the 60s F, it was no beach day in Fort Lauderdale, but we weren’t headed to the beach. Instead, the Gulf Stream beckoned, its western edge a good 15 to 18 miles offshore. With a full main and jib, we made quick work of that and were soon bounding across the roiling, rollicking Stream.

Scrawling notes in my sodden notebook, I recorded the usual early-race mayhem: a couple of headsail changes; a brief, regrettable attempt at flying a spinnaker; back to a small jib and a reefed main. It was my first trip aboard Serengeti, but the consensus among the regulars was unanimous–cranking along at anywhere from 12 to 15 knots, we were hauling the mail. I was perched forward on the weather rail, and it was a wet ride; we occasionally shipped some solid water. My world was especially rocked by one hurtful wave that very literally knocked the wind out of me, another first (and I hope a last).

I went off watch at dusk and was back on at midnight. Overhead, the thick sky was beginning to break up, and the odd star began to shine through. The worst of it was behind us. But the sailing was still very challenging, with the wind shifting steadily through 25 degrees in the lulls and the puffs, and it was imperative that the mainsheet trimmer and driver work closely together. I handled the main for a while and Tripp steered, and we began to sense what the other was about to do without speaking. In the big gusts, I eased the main way off as Bill bore away; once or twice I even had to press the “panic button” that blows the hydraulic boom vang to keep us on our feet. After a bit, it occurred to me that I was thoroughly enjoying myself.

At 0300, the watches changed again. Twenty minutes later, I was down below chatting with seasoned navigator Jack Harvey–who’d done the race at least eight times (that he’ll admit to) and could never remember not beating out through the Bahamas–when suddenly we heard Nanartowich cry, “No helm!” Serengeti’s swift race turned into something altogether different.

Detour to Nassau Chad Weiss was forward trying to snatch some sleep, and Bill Tripp was aft discussing strategy when we lost steerage. Since the “ching” we’d all heard didn’t sound catastrophic, they thought–as did I–that something was remiss with the steering quadrant, possibly a snapped line or a broken block that could easily be jury-rigged or repaired. But upon inspection, it was discovered that the carbon rudderstock had broken free and clear precisely where it exits the hull, carrying the attached blade with it. Happily, we didn’t take on even a spoonful of water.

Navigator Harvey instantly noted our position and quickly assessed our immediate options. And there was Nassau, 40 miles south, dead downwind. All we had to do was get there. There was no shortage of opinions on how that task might best be executed.

Owing to her New Zealand heritage, Serengeti carried an unusual drogue called a Sea Claw from Coppins Sea Anchors (www.paraseaanchor. com), a Kiwi company specializing in emergency gear. It was immediately deployed and for most of the time did a reasonable, though not exceptional, job of keeping the stern to the wind and seas. The main had been dropped immediately after the incident, but someone came up with the idea of hoisting the storm jib to give us some speed and also to counteract the cork-screw effect the drogue had on the stern.

This proved to be a stroke of genius. Not only did this boost our boat speed to a solid 3 knots; the tiny sail also kept us more or less directly on course for Nassau. Every time the bow came into the breeze, the sheeted-home jib would back and send the boat into a controlled jibe. Once on the new board, the sail would fill, and the boat would accelerate until the bow again wandered toward the wind, whereupon the whole process would repeat itself. In this manner, pivoting around its nearly 14-foot keel and slaloming down a heading that wandered through about 30 degrees, Serengeti held an average course straight toward Nassau.

It was a good thing, too. In a call to BASRA, the all-volunteer Bahamas Air and Sea Rescue Association, we learned that even the cruise ships were weather-bound in Nassau. While the BASRA folks were sympathetic to our plight, they didn’t have the resources to lend assistance but asked to be kept apprised of our progress. And a commercial-towing outfit quoted a figure of $10,000 for a lift home. While it was clear we wouldn’t be able to sail right up to a dock, we’d be on our own until just outside Nassau. As Bill Tripp said in a sat-phone call to the authorities, “We’re getting there OK, but we’re going to need someone to catch us once we’re there.”

Sailmaker Mark Ploch reckoned, correctly, that with more speed, we’d have better control, so by midafternoon we’d swapped the storm jib for the No. 4 headsail. Instantly, we were making 6 knots. But the faster speeds proved too much for the drogue, which at 3 knots stayed submerged and provided the necessary drag to maintain course but skipped and planed atop the following waves at anything quicker. And once the drogue was clear of the drink, Serengeti instantly sprang up toward the breeze. (The position of the drogue was also critical to the overall exercise, particularly because the waves were so close together. After a lot of trial and error, it became clear that the device worked best when streaming about 100 feet aft.) We tried trailing sheets and lines aft to induce more drag, but their effect was minimal. Reluctantly, down came the No. 4 and back up went the storm jib.

Late in the afternoon, off Nassau, we rendezvoused with a kind soul in a Mako-type runabout of about 22 feet powered by a 100-horsepower outboard. We used a stretchy anchor rode as a tow line, which in retrospect wasn’t ideal. Skipper Weiss was stationed by the throttle with the engine slowly turning over: “The anchor line was like a big rubber band,” he said later. “Without the jib up, it was very hard to keep the bow down, so when it swung in its maximum arc, I’d put some reverse on to compensate. We’d get a little pull, and it’d whip the boat from one direction to the other. A line with less stretch would’ve worked better. And it was probably way too long. We kept making it shorter and shorter to reduce the bouncing action–the shorter, the better.”

It was slightly hairy negotiating the harbor entrance, but by sundown, we were alongside a dock and thinking about refreshments. Serengeti, sans rudder, was ready for the next chapter. The torn, trashed drogue didn’t fare as well, though it would’ve been a struggle to reach Nassau without it.

Designer’s Postmortem When it was all over, I asked Bill Tripp what he’d learned. His answers were insightful. “I’d never needed a drogue before and now realize how important they can be,” he said.

“The drogue we had wouldn’t stay submerged when we were going fast enough. That was a real problem, a double-edged sword. Because you need the sails to steer, and the sails make you go fast, we had to put on as little sail as possible and not have the boat go more than 4 knots. Our drogue popped out of the water at 3.5 knots. We needed one that worked at 6 knots. When you have a following sea, speed is better than no speed. The less speed you have, the more the waves are throwing the boat around.”

In the aftermath, one of the designers in Tripp’s office tested a number of drogues on The Solent, in England. In the future, Tripp plans on specifying drogues for his new designs and will also incorporate fold-down padeyes aft so there’s a ready place from which to deploy them. “We needed a drogue that wasn’t so dependent on being full, which isn’t a bagful of water,” he said. “The kind you want looks like a huge net–it has a big circle and huge webbing and looks like a cone. It doesn’t have an open/close aspect to it like the one we had. And we didn’t know that. In smooth water, I think the Sea Claw would work well. But it had that aspect where, if you changed half a wavelength on it, suddenly it would surf, and when it surfed, it collapsed. And once you were going 4 knots with it collapsed, it wouldn’t fill again.”

All in all, Tripp described the incident as an eye-opening experience. “In the design process, you can’t imitate a boat without a rudder. It isn’t possible,” he said. “I’ve done all the Newport-Bermuda Race tests where you have to prove you have emergency steering, and you do that by lashing the wheel and then dragging a spinnaker pole back and forth [off the transom]. And you can do that in flat water; it works fine. Out at sea, it doesn’t, particularly if you have to go dead downwind. If you want to set the boat up on a reach or even go upwind, you can do both by trimming the sails, but downwind is the hard one. Because the waves just take the stern and pick your course.”

Tripp, however, was confident that had we been outside Eleuthera in the open Atlantic when the rudder vanished, a high-performance boat like Serengeti would’ve fared well. “I think with a double-reefed main, we could’ve climbed up on the breeze,” he said. “We would’ve sailed the boat by trimming and dumping the mainsail, the old dinghy thing. The disadvantage of a boat like this is that when it breaks its rudder, it’s like a dinghy. On the other hand, the advantage is you can sail it like a dinghy.

“Anyway,” he concluded, “it was certainly an adventure. I wish it hadn’t happened, but since it did, I was glad I was there.”

Epilogue It turned out that it wasn’t a case of whether Serengeti’s rudder would fail or not–it was inevitable–but when it would happen. When the boat was loaded onto a barge to begin its journey from New Zealand to the States two years ago, its rudder clipped the deck due to a problem with uneven hoisting straps. For a variety of reasons, it wasn’t inspected at the time. But the shattered remnants of the carbon post revealed what Weiss called “a catastrophic failure.” There was evidence that the stock had been wearing away ever since the boat was launched.

Even so, within a few weeks Serengeti was fitted with a new appendage and sailed on to Antigua, where in late April she competed in Sailing Week. But in mid-May, the boat suffered major damage to her hull and rig after being struck by a cruise ship while anchored in St. George’s Harbour, Bermuda.

As for the Pineapple Cup, the strong northerlies held on, and nine of the 16 competing yachts beat the old race record of 2 days, 23 hours, with the victorious 75-foot Titan 12 taking over 12 hours off the mark in posting a new record of 2 days, 10 hours, and change. By all accounts, it was a helluva ride.

Then again, so was ours.

Herb McCormick is CW’s editor.

- More: voyaging

- More Uncategorized

Schooner Nina Missing

Editor’s Log: Pitch In for the Plankton

West Marine Announces $40,000 Marine Conservation Grants for 2013

10 Best Sailing Movies of All Time

Kirsten Neuschäfer Receives CCA Blue Water Medal

2024 Regata del Sol al Sol Registration Closing Soon

US Sailing Honors Bob Johnstone

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

- Forum Listing

- Marketplace

- Advanced Search

- All Topics Sailing

- General Sailing Discussions

- SailNet is a forum community dedicated to Sailing enthusiasts. Come join the discussion about sailing, modifications, classifieds, troubleshooting, repairs, reviews, maintenance, and more!

Steering Without A Rudder

- Add to quote

I recently viewed Giu's video on steering without a rudder. And yes, I realize that there is a thread devoted to comments on these videos. This is not directly a comment on his video as much as a follow up question. I hope he returns soon so that he might elaborate for me. I'm not sure that the video shouldn't be called sailing without a wheel or tiller. The techniques that were employed in the video didn't work for me. I was on a boat in the not too distant past that actually lost its rudder . I gotta tell you. There was no steering that boat. We were on a broad reach with only the Genoa flying and fighting a good amount of weather helm . Anyway, all of a sudden the wheel went dead in my hands. The boat came about twice before I could even get the Genoa rolled up. I looked aft and saw; about 100 yards astern a bottom painted blue oval shape bobbing in the seas. I know that I should have tried to balance things out by setting some main and reefing the headsail, but it was blowing 25 to 30 knots and the wheel was manageable. Once the rudder fell off, there seemed to be nothing I could do to keep that boat from heading up. I don't think I would have had the same experience with a full keel boat as opposed to a fin keel. The loss of the rudder on this boat just seemed to prevent it from being able to go through the water in anything that approached a straight line. You should have seen the fiasco of being towed into Coinjock. It was too rough to hip-tow until we got out of open water so the poor guy had to fight this 40+ foot boat swinging back and forth up to 120%. It took over 2 hours to be towed three miles. I don't really know if there is anything that one could do except maybe use the main salon table as a makeshift rudder. I tried dragging warps, putting up sail, nothing worked to be able to control the course of that boat. Anyone have any Ideas? Alex?

Knothead- Flying only a genny should give you lee helm, not weather helm as a general rule. Of course, losing the rudder moves the center of lateral resistance forward, since the rudder is a large portion of the underwater lateral plane on a fin keeled boat. Towing a drogue, with more resistance than plain warps, from a bridle would have probably allowed you to keep the boat on a relatively straight course.

sailingdog said: Knothead-Flying only a genny should give you lee helm, not weather helm as a general rule. Click to expand...

Zanshin said: I had a similar experience with a lost rudder and found my fin-keeled 43 foot boat to be unmanageable. I had a longer tow from a twin engined powerful boat and even though I deployed pretty much every warp, bucket and drag-producing device off the stern I was still going through at least 120 degrees and we had a tow bridle set up. I think that there is a HUGE difference between steering a fin-keeled boat without using the rudder and steering the same fin-keeled boat that is missing the rudder. The surface area of the rudder is quite large compared to the surface area of the fin keel rudder and the two are separated by just a bit less than half the hull length. Having both lateral surfaces gives a lot of directional stability, whereas if the rudder aft is missing then the fin keel acts like more of a pivot than anything else. Click to expand...

I have always wondered, that if you were towing a dinghy and you lost your rudder, if you attached an anchor to the dingy and put it out to say 20 feet. If that would be enough drag at the stern to allow use of sails and mover the lateral plane...

How doe one find out about a rudder construction on a sailboat that is not manufactured anymore?

I had a similar experience with a lost rudder and found my fin-keeled 43 foot boat to be unmanageable. I had a longer tow from a twin engined powerful boat and even though I deployed pretty much every warp, bucket and drag-producing device off the stern I was still going through at least 120 degrees and we had a tow bridle set up. I think that there is a HUGE difference between steering a fin-keeled boat without using the rudder and steering the same fin-keeled boat that is missing the rudder. The surface area of the rudder is quite large compared to the surface area of the fin keel rudder and the two are separated by just a bit less than half the hull length. Having both lateral surfaces gives a lot of directional stability, whereas if the rudder aft is missing then the fin keel acts like more of a pivot than anything else.

Knothead- What kind of boat was this??? If the rudder was large enough and the keel small enough in area, the CLR could have shifted forward enough that a large genny would give weather helm. That would probably be the case on Gui's boat if he lost his rudder, since the fin keel on his boat is really just a thin strut supporting a bulb...rather than a keel with any real surface area.

Last time I heard this being bounced around, the consensus seemed to be that the best jerry-rig would be to use a spinnaker or whisker pole with some large u-bolts (kept for that purpose) to affix a door or table (pre-drilled) to the end of the pole, and then using that "steering board" deployed from the stern, so the board was as far aft of the boat as possible in order to get more leverage against the pivoting on the keel. Apparently a lot depends on the hull shape and stability and balance, or lack thereof. A boat that balances well and steers well under just sail trim (with no rudder effort) should do better than one which always needs some rudder. But I don't think I know anyone who would be willing to drop their rudder and then go out for practice.[g]

If the incident had occurred offshore somewhere, I would have definitely started drilling holes in the table but It was easier to call for a tow where we were. It does seem like a good idea to be prepared to lose a rudder. U-bolts are cheap and I guess you could stick a candle in the holes in the table. But it seem to me that having some steel in your rudder post would be a pretty good idea too. Frankly though, I think it would be a lot easier to rig a jury rudder on a full keel boat.

In the current issue of Sail (I just got it in the mail yesterday), there is a story about a boat racing in the Cleveland Race Week on Lake Erie that lost its rudder and eventually sank while being towed to shore. The rudder post hole could not be plugged and it filled the bilge and the cockpit faster than the pump could pump it out. Moral of the story was to check the rudder before putting the boat in the water in the spring.

Ouch, that's one I hadn't thought of. With a wheel rather than tiller, the rudder post will be an open thru-hull if the rudder falls out, rather than shearing below the hull. I suppose that means a rather large damage control plug should be kept back in there, with provision to get a collision mat rigged under the boat in order to really close it off in case a piece of hull goes with it. I guess "cushions" for a Real Boat really should have multiple grommets sewn into them, so they could readily be used for that purpose. Sure would puzzle the sailmaker when you bring in your CUSHIONS and say "put a one inch grommet in each corner, with reinforcing." Break Out Another Thousand...

- ?

- 173.8K members

Top Contributors this Month

- Mar 12, 2024 Blue Water Medal Presented to Kirsten Neuschäfer as CCA Honors Top 2023 Ocean Sailors

- Mar 11, 2024 Commodore’s Awards to Hamilton, McCurdy, and the Greens

- Hide Banner

- Member Login

A Guide to Steering without a Rudder

A Guide to Steering without a Rudder

Methods and Equipment Tested

Michael Keyworth

This guide is the result of multip le tests conducted in the fall of 2013 off of Newport, RI . The test vessel was a modified MK I Swan 44 , Chasseur . The purpose of the tests was to determine the best method and equipment to effectively steer the vessel to a safe port in the event of catastrophic rudder failure. The goal was to utilize the equipment normally taken on the vessel on offshore passages or races. The overriding premise was; utilization of an efficient and controllable object to create drag and transmit to directional stability which results in the desired directional stability. It was my view that a drogue might be used to exert the appropriate drag. I further felt that a small drogue might provide the needed drag but not significantly impede the speed of the vessel.

Chasseur has been modified in the following relevant ways; the rudder skeg was removed and replaced with a modern spade rudder which is carbon fiber with a Carbon fiber shaft, the keel has been modified to a modern shape fin with a shoe, the mast is carbon fiber and 6 feet taller than original. For the purposes of the tests, the rudder was removed and the rudder port was blocked off.

I was familiar with and had onboard Chasseur a “ Galerider ” made by Hathaway, Reiser & Raymond of Stamford, Connecticut. I contacted Wes Oliver at Hathaway and he arranged to make several prototype drogues for the tests. We were equipped with: a 12inch diameter drogue with a 3 part bridle, a 12inch diameter drogue with a 4 part bridle, a 18 inch diameter drogue with a 4 part bridle, a 30 inch drogue with a 4 part bridle and a 36 inch drogue with a 4 part bridle.

The purpose of the test was to establish whether direction could be controlled under the following “underway” conditions using any of the drogues supplied:

W ith sail trim alone

M otoring using a drogue

S ailing upwind using a drogue

S ailing downwind using a drogue

M otorsailing using a drogue

B eing towed using a drogue

Size of drogue proved to be very i mportant. The findings were definitive:

The two 12 - inch drogues provided no directional stability.

The 18 - inch drogue provided marginal control in winds under 10 knots

The 30 - inch drogue was very effective in all conditions that were tested and resulted in approximately 1 knot reduction in boat spe ed. In wind conditions over 20 knots of windspeed a chain pennant needed to be added to reduce cavitation.

The 36 - inch drogue worked similarly to the 30 inch drogue but affected boat speed by approximately 1 ½ knot s .

Rigging

Two spinnaker sheets were used. I believe that spinnaker sheets are appropriate as they are generally sized based on length of boat. The sheets were led as two sides of a bridle (port and starboard) from amidships snatch blocks, thru amidships chock or similar and clipped into the swivel at the lead for the drogue. The tails were lead aft to the primaries in the cockpit. It is important to rig this so as to provoke the least amount of chafe as these lines will become your steering cables. We found that the leads need to be led to the axis of the keel as the boat will rotate on the keel. This point is probably somewhere near amidships . Note: The afterguy block may be ideal for the bridle lead.

Some prior guidance suggested that a lead to the quarters of the transom is the best. Our findings are that this restricts the transom from swinging, therefore preventing the desired change in course.

Fig 1 (bridle set up)

During rough and/or windy conditions it may be necessary to add weight to the d rogue to keep it from cavitating . Using the concept of being limited to equipment that is already on board, we were able to use various lengths of chain attached to the swivel at the lead for the drogue. At the other end we effectively used a spare swivel shackle and attached one end to the forward end of chain and the other to the bridle from the boat. It is important to have swivels at both ends as the drogue will tend to rotate as it is pulled along. The bridle may get twisted up but this does not seem to affect the control. During our tests the length of “scope” of the bridle/drogue did not seem important. The nominal distance aft from the transom varied from 50 feet to 120 feet. It may be necessary to add scope in extreme conditions. I found that reference of the drogues position was valuable information. I whipped colored marks at 10 foot intervals on both spin sheet/bridle which gave a quick reference; this could be done with tape or magic marker.

Findings

Controlling direction with sail trim alone : Not Possible!!!

Control direction while motoring using a drogue - This is the easiest scenario. A wide range of control is available. This can be done with only one person, easily. While testing we were able to execute multiple 360 degree turns with full control. Doing 5.5 knots a full 360 can be executed in 4-4 ½ boat lengths. While motoring, adjustments of 2-3 inches results in 5-10 degree course change.

Controlling direction while sailing upwind using a drogue - The same principals apply except that there needs to be cooperation between the sail trimmers and the “helmsperson” (bridle trimmer) . In this scenario the main must be up, even if reefed, the jib may be overlapping, but more con trol may be achieved with a non- overlapping jib. Tacking takes coordination but, once you get the hang of it, no problem- - traveler up, back the jib and come on to the new tack. We were able to achieve 30-35 degrees apparent sail angle . In large seas wider angles should be expected.

Controlling direction while sailing downwind using a drogue: When the wind is aft of 90 degrees apparent it is necessary to take the mainsail down and sail under Jib alone. It will be necessary to have an attentive jib trimmer in addition to a helmsperson on the drogue controls. The size of the jib will have to be factored in based on wind and sea conditions. We also found that the deeper the angle the harder it was to have fine control of direction. Jibing is pretty straightforward by easing the jib and rotating the drogue.

Controlling direction while motorsailing using a drogue- The same principals apply as in sections on upwind and downwind sailing.

Controlling direction while being towed using a drogue- This test, I felt was important because most successful results of rudder loss has a component of a tow of great and small distances to a safe harbor. In this situation we were towed by a 27’ Protector with two 250 HP outboards. A towing bridle was made up on Chasseur and attached to the tow line from the Protector. At 3 Knots the bow was swinging from port to starboard to the end of the tether. At 4 knots it was very difficult to stand on the foredeck. We deployed the 30 inch drogue as rigged for sailing and motoring. The results were immediate. Towing at 7 knots was comfortable and straight, requiring very little input from the helmsperson.

This is an important finding as it suggests that a drogue should be carried at all times so that assistance can be rendered safely, even inshore.

Additional Findings/ FAQ s

If you lose your rudder- first confirm that the rudder port is not leaking- if it is you must first deal with the flooding issue. Once the flooding issue is stabilized move on to the next step of getting home or assistance.

Communicate with Race Officials if you are racing and/ or with those onshore who will worry about your situation.

Communicate with vessels nearby if in need of immediate help away from a lee shore or collision avoidance in shipping lanes.

Choose your safe harbor destination based on wind direction predictions, ease of access, proximity, repair facilities, etc. Do not feel that you need to en d at the original destination port.

If you lose your rudder, it is likely that you either hit a submerged object or that the conditions were severe. Remember that you have time. Relax, storms don’t usually last more than a cou ple of days. Deploy your drogue or sea anchor and get some rest.

Each time that we went testing we learned something new . Don’t be afraid to try something that you think might help, i.e. longer scope, move lead of bridle forward or aft, larger/smaller jib, reef/no reef , etc .

An unanswered question is how a drogue will work with different types/styles and underbodies than Chasseur. My personal view is that a drogue will be an effective tool to have on any type of boat and its deployment can be adapted to the type of vessel that uses it.

Offshore you will have room to maneuver. Take your time and don’t stress ab out steering an accurate course.

The engine is your f riend. You will find that using engine power will provide the greatest degree of control- speed and direction. Use the engine to deploy sails, to get rest, or to retrieve the drogue- retrieval is easiest when the boat is stopped. Be careful to not tangle the bridle in the prop. This was never a problem during our trials. This was probably because; towards the end of trials we used a 5 f oo t chain pennant to help the drogue from cavitating. The chain component is an important one. I chose the use of chain to weight the drogue because ISAF Offshore Prescriptions require that an anchor with appropriate ground tackle be carried, so it need not be carried as additional gear . Others venturing offshore tend to take ample ground tackle to accommodate the use for other purposes. On a practical matter, I think that it makes sense to have different lengths of chain for required circumstances. It also makes sense that a longer chain can be made shorter using the rig cut away tools as required by the rule. A shorter chain can be made longer using shackles to join shorter lengths.

How heavy is the Galerider ? A standard 30 - inch drogue weighs in at 9 pounds and is stored in a bag that is 15 inches in diameter and 5 inches thick. The standard 36 - inch drogue weighs 13.2 pounds and stores in a bag that is 18 inches in diameter and 4 inches thick.

One of the difficulties that you wi ll face to determine where the helmsperson is stat ioned and has access to heading or a compass. Something that you may want to consider, as you equip for an offshore passage is the purchase of a backup compass which can be remotely mounted. Boats equipped with modern electronic packages may have the option of display of heading for both helmsperson and trimmer/s .

It would be prudent for any offshore sailor to practice the depl oyment of a drogue for speed reduction sailing downwind in large seas and to rig and use as a means of steering. This would help to identify the gear necessary to deploy and provide a ready plan to implement if necessary.

The transition from drogue to drogue steering or vise versa may be easier than you think.

A trick that we learned is that you can cleat off one of the bridle lines and have control with the other. If you were to cleat off the port bridle line a turn to port would result from easing the starboard bridle and a subsequent change to starboard would result from trimming the starboard bridle. This lazy mans approach gives the helmsperson more flexibility and physical relief.

What I learned from the extensive testing is that you can achieve a great deal of control using a drogue . I would bet that if any boat is able to sail 100+ miles wit hout a rudder to a safe port , the crew will want to take a victory lap around the harbor to “show off” the newfound skill and seamanship ability .

One last thought. Having sailed over 150,000 miles at sea I have seen many things and have been able to overcome all sorts of adverse conditions, I still have many concerns and reservations. One concern is that of rudder loss and how to deal with that possibility. This test should help all who go to sea with that possibility. The other concern that haunts me each time I go to sea is the amount of floating debris and other objects that may affect the ability of even the most seamanlike sailor to safely passage from place to place. The possibility of being holed or sunk from collisions with floating debris is real. Most of the stories I have hear d about boats at sea that have become rudderless have resulted in the abandonment of those vessels. These abandoned vessels represent a threat to those fellow sailors who put to sea and put them unnecessarily at risk.

Similar Subject

- Suggested List of Tools and Spares

Recent Articles

Can You Sail Without a Rudder?

Have you ever wondered if it’s possible to sail without a rudder? The answer is yes, it is.