Home » American History » How Riverboats and Steamers Shaped American History

How Riverboats and Steamers Shaped American History

Before trains and automobiles, it was riverboats that connected America. You can learn more about the rich American tradition of steamships here.

Throughout American history, there have been many modes of transport that forever changed the face of this country. Everything from the development of automobiles to the railroad, canal boats, and even the covered wagon—they’ve all played a big role in bringing us to where we are today.

The steamboat is part of this rich history. While there are lots of different types of steamboats, some of which are ocean going, we’ll focus on the riverboat variety here. Prior to automobiles and railways, it was rivers that connected one part of the U.S. to another. Steamboats were responsible for ferrying people and goods all over the country and to the coasts where shipments could then be transported overseas. Let’s jump in and start with the earliest known steamboat history.

Steamboats Invented in Europe

Though these boats were responsible for reshaping America, they were originally developed in Europe. You see, it was in the late 1600s when early experiments on the steam engine began. These were led by the French inventor Denis Papin, and Thomas Newcomen of England. It started with a device known as the steam digester, which was an early kind of pressure cooker. From there, these two men experimented with pistons, and Papin eventually suggested that this technology could be used to operate a paddlewheel boat.

Both men made designs attempting to power a boat, though neither of their designs worked that well. Still, innovation is part of the human spirit, so soon, other inventors followed suit. English scientist John Allen patented the first steamboat in 1729. Over the next thirty-some years, other inventors attempted to improve on steam engines and steamboats, one of whom was William Henry from Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He produced his own steam engine in 1763, which he put on a boat. The boat sank—but it’s thought perhaps Henry’s work inspired others to keep innovating.

The Rise of Steamboats in America

From there, it was a race to develop working steam engines—and working steamboats. Several people made working steamboats in the 1780s. In the United States, John Fitch of Philadelphia launched a steamboat in 1787, and it proved such a success that by 1788, he was operating a commercial steamboat service that followed the Delaware River between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey . This was a passenger boat that could carry up to 30 people, traveling between seven and eight miles per hour.

Unfortunately for Fitch, while his boat was a success, his business was not. The route on which his boat traveled was one already well covered by roads and wagons, so there wasn’t much need for a passenger boat.

But later, Robert Fulton, an American inventor who found himself intrigued by the possibilities of steamboats, ended up creating his own vessel in 1807. This was the North River Steamboat , which later became known as the Clermont —and it could be considered the boat that started the steamship revolution in the U.S.

The Clermont was pretty incredible for the time. It traveled the Hudson River between New York City and Albany, making the 150-mile trip in as little as 32 hours. Because of its capabilities, it became the first commercially successful steamboat in the U.S.

In the wake of the Clermont’s success, steamboats began to proliferate around the United States—especially along the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, where they were instrumental in not only ferrying passengers up and down long stretches but also hauling grain, lumber, supplies or anything else that needed to be moved long distances. These riverboats also grew in prominence in the western United States during the California Gold Rush, usually pressed into service to carry miners and mining supplies closer to the gold fields.

Riverboats During the Civil War

When you hear about Civil War boats, the two that most people are familiar with are the Monitor and the Merrimack , which were ocean-faring steamships called “ironclads.” They receive most of the historical attention because truly, these two ships were a revolution of their times. But there’s a whole other side to Civil War naval history that you don’t often hear about—and that was the battles waged by Union and Confederate riverboats.

Away from the East Coast, the naval war was fought for control of the major rivers, most especially the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers—and this involved paddlewheel boats that had been converted into warships. These river battles were waged by monitors, which were heavily armed but lightly armored smaller rivercraft, and ironclads, which were boats that had been heavily armored with iron plates. Some of the war’s most famous battles, like the Battle of Vicksburg, involved the use of riverboats. Between the Vicksburg battle and the seizure of New Orleans, this secured the Mississippi River for the Union Army, enabling them to transport men and supplies up and down the river.

The Heyday of America’s Greatest Riverboats

To this day, the Mississippi River is still a major shipping lane within the United States, though nowadays, you’ll find a variety of craft going up and down its waters. Through the 19 th century to the early parts of the 20 th century, however, it was the paddlewheel steamer that dominated the Mississippi—and other major rivers, too. Some of these boats were so famous that they became state symbols, like the Iowa , which was an 1838 steamer that is part of Iowa’s state seal. The Anson Northup is another famous steamer that in 1859, became the first to cross over from the U.S. to Canada on the Red River.

During this time, steamers were a major part of what drove American expansion. Their speed and power meant that people could transport more goods and passengers than ever before, which is a big part of the reason why port towns flourished so well—because steamers were bringing in the goods from the heartlands that would be transported for trade overseas. These rivercraft became iconic, something that people all over the United States took great pride in as symbols of progress and prosperity.

Eventually, though, riverboats began to wane in popularity. There were a couple of reasons behind this. For one thing, the big steamers were incredibly dangerous. Ultimately, most of these boats would either burn down or they’d be destroyed when the powerful boilers that powered them exploded. They were wooden ships, after all, powered largely by wood fires since wood was so easy to procure along the rivers on which they ran. Accidents were quite frequent, and many who traveled on them took their lives into their own hands. In places like Alton, Illinois, homes along the river even featured platforms called “widow’s walks,” which were rooftop platforms where women would watch for their husbands to come home on the riverboats they crewed. To put into perspective how dangerous these crafts were, the Scientific American reported in December 1860 that 487 people had died that year in steamboat accidents.

Even though steamers were dangerous, the danger wasn’t the primary factor behind their decline. Actually, it was the development of the railroad. As more and more rail lines began to spread across the United States, riverboat popularity waned. Railroads had too many advantages—they were faster, capable of hauling more, they were safer, and they could reach landlocked places that didn’t have river access.

Even so, riverboats never did go out of service entirely. Today, you’ll still find them all over America’s largest rivers. Some of those old paddle steamers that were once so iconic are still around, though these days, most are replica pleasure craft designed with modern engines that are infinitely safer than the old wood-fired boilers that used to run them.

Riverboats are still a rich American tradition, and they truly were a formative part of American history. If you ever have the opportunity, schedule a cruise or even an afternoon tour on one of America’s replica paddleboats. It’s an experience that will take you back in time.

You may also like

Echoes of Time: The Living Legacy of Old Fort Niagara

Bob Waldmire: The Free Spirit of Route 66

The Birth of Prosthetics

Cleveland’s Man of Steel

A Beacon of History on Lake Ontario

How Martin Luther King Jr. Day Became a Federal Holiday

Will founded Ancestral Findings in 1995 and has been assisting researchers for over 25 years to reunite them with their ancestors.

Main Navigation

A History of Riverboats in Mississippi

The mighty Mississippi river stretches from Northern Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. The second-longest river in the United States, the Mississippi is integral to the history of America — particularly in the state of Mississippi. Riverboats facilitated travel, commerce, and cultural exchange within Mississippi and beyond. Learn more about the impact of Mississippi riverboats in this post from Visit Mississippi .

Riverboats: The Early Days

While people have navigated the waters of the Mississippi River for centuries, steamboat technology was not viable until the early 1800s. The first steamboat to travel the Mississippi was the New Orleans, whose October 1811 maiden voyage began in Pittsburgh, PA, and ended in New Orleans after traveling along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

The New Orleans stopped in Natchez in December 1811 before continuing to its final port in New Orleans. First established by French colonists and later ruled by the Spanish, Natchez was an important center of trade and cultural exchange.

The Golden Age of the Steamboat

By the 1830s, steamboats existed all along the Mississippi River and its major tributaries. The growth of Mississippi’s riverfront communities, such as Bolivar, Commerce, and Greenville, can largely be attributed to the riverboat trade. Riverboats also brought new settlers to the state, helping to speed up agricultural development in the fertile Mississippi Delta.

Propelled by steam-driven paddle wheels, steamboats could navigate the river more quickly and effectively than barges or flatboats. They carried goods such as cotton, timber, and livestock up and down the river, expanding trade throughout the growing U.S. However, steamboats could be dangerous — the boilers used to create steam could build up too much pressure and explode. Steamboats were also susceptible to hitting obstacles such as rocks or logs, which could cause them to sink. This created a growing industry for a smaller type of riverboat called a “snagboat.” Snagboats patrolled the Mississippi River looking for tree stumps, debris, or other hazards and removing them before they damaged larger steamboats.

Wealthy Mississippians could enjoy leisure travel on a showboat — a riverboat used for theater and musical performances. Showboats were ornately decorated and would announce their arrival at a port by playing music that could be heard for miles.

Riverboats During the Civil War

During the years after Mississippi’s secession from the Union, many steamboats were used to support the Confederate Army. Riverboats carried troops, provisions, and supplies along the Mississippi during the Civil War. Demand for ships was so high that both the Union and Confederate governments chartered steamboats. Riverboats also played a role in the defense of Vicksburg, an important Confederate stronghold that connected the South to the Western states.

Gaming on the River

Riverboat gambling became popular in the early 1900s due to legislation surrounding gaming. By keeping poker, roulette, and other games of chance restricted to a riverboat, business owners could evade the anti-gambling laws that were in effect on land in states along the Mississippi River. Riverboat gaming in Mississippi was legalized in 1993, but unfortunately, Hurricane Katrina destroyed many riverboat casinos. In response, Mississippi lawmakers allowed casinos to move 800 feet inland.

However, you can still find a few riverboat casinos throughout the U.S. In Mississippi, visitors can try their luck at the Ameristar Casino Hotel in Vicksburg , a riverboat-style casino and hotel located right on the water.

Mississippi Riverboats in the Present Day

According to National Geographic, by 1900, the growth of railroads across the U.S. significantly reduced the demand for transporting goods and people via steamboat. Many riverboats were retired, but a few showboats remained as a testament to this period in history.

The popularity of riverboats continues to thrive in the Magnolia State. Today, tourists can enjoy the relaxing and immersive experience of river cruising. These luxury expeditions offer a unique way to travel the Mississippi, where guests can admire the breathtaking scenery along the waterway. First-class accommodations, fine dining, and a variety of things to do can be expected on a luxury tour on the Mississippi. Companies such as American Cruise Line and Viking River Cruises offer a variety of cruises that vary in duration and cities visited, like Vicksburg and Natchez.

Plan Your Trip With Help From Visit Mississippi

If you’re planning a trip to one of our historic riverfront cities like Natchez, Vicksburg, or Greenville — or anywhere else in the Hospitality State — Visit Mississippi is here for assistance.

Plan your next trip to Mississippi using our complimentary trip planner tool that helps you map out all your must-see attractions, restaurants, and lodging options. Whether you’re here for a week or just passing through, you’ll find a wealth of information about Mississippi history and culture on the Visit Mississippi website. For more information, contact us today.

Email Updates

Discover new ways to wander.

Get your free Mississippi official Tour Guide.

- Things to Do

- Places to Stay

- Experiences

- Accessible Travel

- Meetings and Conventions

- Group Travel

- International Travel

- Welcome Home Mississippi

- Mississippi Tourism Partners

Copyright ©2024 Mississippi Development Authority All Rights Reserved. Privacy Policy

Privacy Overview

Search by keyword or phrase.

The History of Steamboats

Before Steam Engine Trains, There Was the Steamboat

- Invention Timelines

- Famous Inventions

- Famous Inventors

- Patents & Trademarks

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

The era of the steamboat began in the late 1700s, thanks initially to the work of Scotsman James Watt. In 1769, Watt patented an improved version of the steam engine that helped usher in the Industrial Revolution and spurred other inventors to explore how steam technology could be used to propel ships. Watt's pioneering efforts would eventually revolutionize transportation.

The First Steamboats

John Fitch was the first to build a steamboat in the United States. His initial 45-foot craft successfully navigated the Delaware River on August 22, 1787. Fitch later built a larger vessel to carry passengers and freight between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey. After a contentious battle with rival inventor James Rumsey over similar steamboat designs, Fitch was ultimately granted his first United States patent for a steamboat on August 26, 1791. He was not, however, awarded a monopoly, leaving the field open for Rumsey and other competitive inventors.

Between 1785 and 1796, Fitch constructed four different steamboats that successfully plied rivers and lakes to demonstrate the feasibility of steam power for water locomotion. His models utilized various combinations of propulsive force, including ranked paddles (patterned after Indian war canoes), paddle wheels, and screw propellers. While his boats were mechanically successful, Fitch failed to pay sufficient attention to construction and operating costs. After losing investors to other inventors, he was unable to stay afloat financially.

Robert Fulton, the "Father of Steam Navigation"

Before turning his talents to the steamboat, American inventor Robert Fulton had successfully built and operated a submarine in France but it was his talent for turning steamboats into a commercially viable mode of transportation that earned him the title of the "father of steam navigation."

Fulton was born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1765. While his early education was limited, he displayed considerable artistic talent and inventiveness. At the age of 17, he moved to Philadelphia, where he established himself as a painter. Advised to go abroad due to ill health, in 1786, Fulton moved to London. Eventually, his lifelong interest in scientific and engineering developments, especially in the application of steam engines, supplanted his interest in art.

As he applied himself to his new vocation, Fulton secured English patents for machines with a wide variety of functions and applications. He also began to show a marked interested in the construction and efficiency of canal systems. By 1797, growing European conflicts led Fulton to begin work on weapons against piracy, including submarines, mines, and torpedoes. Soon after, Fulton moved to France, where he took up work on canal systems. In 1800, he built a successful "diving boat" which he named the Nautilus but there was not sufficient interest, either in France or England, to induce Fulton to pursue any further submarine design.

Fulton's passion for steamboats remained undiminished, however. In 1802, he contracted with Robert Livingston to construct a steamboat for use on the Hudson River. Over the next four years, after building prototypes in Europe, Fulton returned to New York in 1806.

Robert Fulton's Milestones

On August 17, 1807, the Clermont , Robert Fulton's first American steamboat, left New York City for Albany, serving as the inaugural commercial steamboat service in the world. The ship traveled from New York City to Albany making history with a 150-mile trip that took 32 hours at an average speed of about five miles per hour.

Four years later, Fulton and Livingston designed the New Orleans and put it into service as a passenger and freight boat with a route along the lower Mississippi River. By 1814, Fulton, together with Robert Livingston’s brother, Edward, was offering regular steamboat and freight service between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi. Their boats traveled at rates of eight miles per hour downstream and three miles per hour upstream.

Steamboats Rise Can't Compete with Rail

In 1816, when inventor Henry Miller Shreve launched his steamboat, Washington , it could complete the voyage from New Orleans to Louisville, Kentucky in 25 days. But steamboat designs continued to improve, and by 1853, the New Orleans to Louisville trip took only four and a half days. Steamboats contributed greatly to the economy throughout the eastern part of the United States as a means of transporting agricultural and industrial supplies. Between 1814 and 1834, New Orleans steamboat arrivals increased from 20 to 1,200 each year. These boats transported passengers, as well as cargoes of cotton, sugar, and other goods.

Steam propulsion and railroads developed separately but it was not until railroads adopted steam technology that rail truly began to flourish. Rail transport was faster and not as hampered by weather conditions as water transport, nor was it dependent on the geographical constraints of predetermined waterways. By the 1870s, railroads— which could travel not only north and south but east, west, and points in between—had begun to supplant steamboats as the major transporter of both goods and passengers in the United States.

- The History of Transportation

- Biography of Robert Fulton, Inventor of the Steamboat

- John Fitch: Inventor of the Steamboat

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- The Steamboat Clermont

- Building the Erie Canal

- The History of Elevators From Top to Bottom

- The Railways in the Industrial Revolution

- The Sinking of the Steamship Arctic

- War of 1812: Battle of New Orleans

- Steam in the Industrial Revolution

- History of Airships and Balloons

- Notable American Inventors of the Industrial Revolution

- The Development of Canals in the Industrial Revolution

- The Basics of Magnetic Levitated Trains (Maglev)

In their golden age, riverboats were our nightclubs, our theater district, our parade ground

A look back at the history of the Mississippi River

by Jeannette Cooperman

June 8, 2011

Photograph courtesy of Ed Lekosky

Sometimes it seems like all we know of the river is fireworks and gambling. And floods. But in the late 1800s, there could be as many as 1,200 steamboats out on the river at once. Instead of a banquet at a stuffy hotel, a fundraiser might be a moonlit cruise on the Charles P. Chouteau side-wheeler. Orphans were taken on “fresh-air excursions”; courting couples picnicked on the water on Sunday afternoons. Upriver, boys canoed out every time a steamship glided past, hoping a few of those passengers in white linen and straw hats would laugh at their antics and

toss coins.

The river was not, in those years, a sullen and muddy conveyor belt for barges. There were circus boats stuffed with clowns and poodles; theater boats wailing over villainy; opera boats that sent heralds ashore to trumpet their performances. Minstrels did the Cakewalk and the Buzzard Lope and the Buck and Wing, told tall tales, sang spirituals, shook tambourines, mocked current events. All the persuaders were on the river: preachers and card-readers, lecturers on mesmerism and the significance of bumps on the skull.

A boat’s trial run was always a holiday—on the John H. Dickey ’s first outing, February 11, 1858, champagne corks popped and guests raised an earnest toast to the captain: “May he pass down the river of life without drifting on the rocks of destruction or the sandbars of deceit.”

On Independence Day 1870, steamers ran excursions down the river, and onlookers watched the Robert E. Lee churn the water, sending up four-foot waves as she raced ahead of the Natchez to win the great race from New Orleans. The guns at Jefferson Barracks fired a salute, and she returned it as she steamed by.

Eight years later, the Veiled Prophet sailed up as though on the River Styx; he would arrive in this fashion every year for decades, standing masked on the hurricane roof of a boat draped in purple and gold, as all the boats along the levee blew their whistles in deference.

On September 9, 1886, a crowd gathered to watch President Andrew Johnson step onto the deck of the Andy Johnson . He was welcomed by three steamers lashed together and many more fanning out behind them to represent the 38 states then in the Union. In October 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt stood waving on the deck of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Mississippi steamer, and the steamboat parade in his honor gathered more and more boats as it made its way downriver.

Even when the river rose, there were grand excursions to see the flooded bottomlands of Illinois from the upper decks of these cake-tiered ships.

And then they began to die off. The Charles P. Chouteau , the first electrically lit steamboat St. Louisans ever saw, burned on the river in 1887. Over the next century, the river’s amusements faded. The grandest boats were anchored, gambled on, scrapped. Soon the

brightest hope would be a gondola.

P.O. BOX 191606 St. Louis, MO 63119 314-918-3000

Company Info

Publications.

- St. Louis Magazine

- Newsletters

- Custom Publishing

- Digital subscriptions

- Manage my account

- Purchase back issues

Copyright 2024 SLM Media Group. All rights reserved.

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, river of history - chapter 4.

Last updated: November 22, 2019

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

111 E. Kellogg Blvd., Suite 105 Saint Paul, MN 55101

651-293-0200 This is the general phone line at the Mississippi River Visitor Center.

Stay Connected

- S&D Reflector

- J. Mack Gamble Fund

- Subscriptions

- Annual Meeting

Who We Are

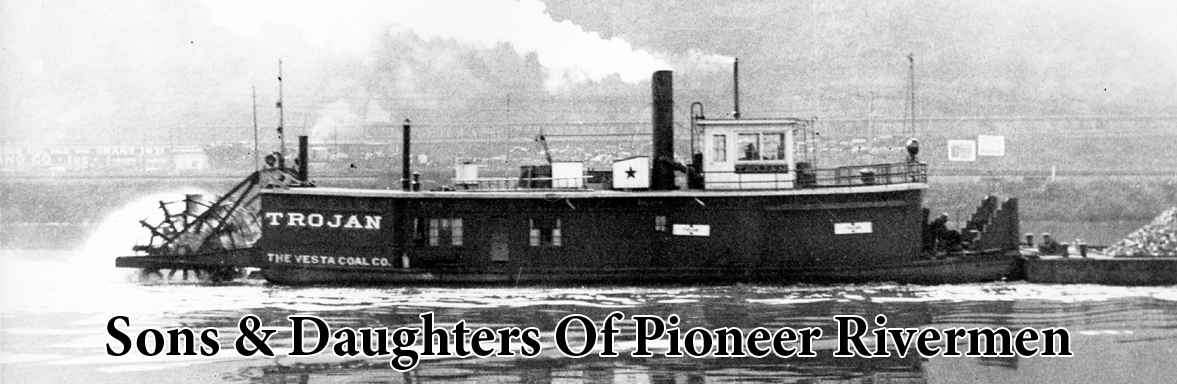

The Sons and Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen (S&D) was established in 1939 to perpetuate the memory of Pioneer Rivermen and for the preservation of river history.

Join the former and active riverboat captains, crew and their families, historians, artists, model builders and those with an interest in the history of the people and boats of the Mississippi River system in sustaining a uniquely American tradition. Subscription is not restricted to descendants of river pioneers, the only requirement for a subscription is in interest in river history!

83rd Annual Meeting - September 15th & 16th, 2023

History In Your Own Backyard Video Showcasing S&D

Adjunct Organizations

- Ohio River Museum

- Inland Rivers Library

- Blennerhassett Museum

Other River Museums

- Ohio Valley River Museum - Clarington, OH

- Point Pleasant River Museum & Learning Center - Point Pleasant, WV

- Old Lock 34 Visitor Center & Museum - Chilo, OH

- Howard Steamboat Museum - Jeffersonville, IN

Sail Aboard a Floating Masterpiece to Discover a New Side of America’s History

For those yearning for something deeper, a voyage down America’s waterways on an authentic paddlewheel riverboat offers a rich discovery of the continent

Since time immemorial, rivers have represented a fundamental exchange—their flow and direction providing the essential ingredients throughout history for burgeoning cities and towns, transportation, trade—even life itself. With that, it’s no surprise that cruising along gentle waters transports us to a place of stillness and peace, sparking a curiosity for the people who traveled these waters before us.

And, aboard a classic American riverboat, like those of American Queen Voyages, a deeper connection with the North American continent, its history, people, and legacy are never far. The flagship vessel, American Queen , is a gentle soul packaged with ornate detailing, inviting visitors to revel in new adventures onboard through its world-class dining, relaxation, enrichment and onshore excursions. With history all around, a dedicated interpreter provides context onboard. And, with vessels ranging from iconic paddlewheelers to state-of-the-art ships, no two trips are quite alike.

To see some of America’s natural beauty and history come to life, read on to discover it for yourself.

Steamboat History

One-hundred-and-fifty-years ago, before the adoption of widespread train travel, rivers were America’s main source of trade, providing necessary resources to rapidly expanding ports and their growing developments. Even earlier still, Native American peoples had utilized these rivers for thousands of years—including the Mississippi, which later became one of the country’s most essential waterways.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/08/33087c41-cac5-4f49-a58a-3b0f38bde5cb/americanqueenvoyages-19962018_pgjvcp-1_1-v1.png)

Today, the lower Mississippi offers a glimpse into an American past that’s often overlooked. Small towns brimming with history welcome visitors to their shores, while massive barges transporting grain and cotton bypass tugboats assisting ocean-going vessels up the waters of this incredible marine highway. Along its banks, bald cypress and Spanish moss draped trees stand watch, and deer and muskrats make their homes. The river’s slow, lapping waters carry a sense of tranquility, calling to mind a simpler time where river cruising was America’s main form of travel—and an elegant one at that.

American Queen History

American Queen Voyages’ fleet of classic American riverboats offer passengers an opportunity to experience a unique chapter of history—whether it’s along the Mississippi or gliding upon the bucolic rivers of the Pacific Northwest—forging a deeper connection to the continent itself, as well as its history and heritage in the process. American Queen is the company’s flagship vessel, a masterful recreation of a Victorian-era steamboat. The 418-foot-long vessel—believed to be the largest steamboat ever built—boasts 213 staterooms, six passenger decks, and a wealth of gingerbread fretwork. It even has a genuine steam engine. “The engine was pulled out of the U.S. dredge Kennedy,” says Frank Rivera, the Queen’s riverlorian (a term that means part-historian, part purveyor of river lore). “She literally is the queen of the river.”

The steamboat revolutionized trade upon waterways. In 1803, American inventor Robert Fulton showcased his first steamboat prototype in Paris, where he caught the attention of American Ambassador to France, Robert Livingstone. The two formed a partnership, and after returning to the States, created the New Orleans , a small demo boat designed with innovative steam-powered propulsion, which allowed commerce to travel upstream, as well as down, for the first time ever.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/db/15db9103-9262-4746-bc99-053d47dd8eb5/americanqueenvoyages-sailing_day_lock_boat_ext_282_of_1529_1-v1.png)

In 1811, the New Orleans made its inaugural journey from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. Although its billowing smoke and the roar of the boat’s engine originally instilled fear in those along the riverbanks, by the time the New Orleans reached its namesake city, it was met with a hero’s welcome. People cheered as—rather than dismantling the ship at the voyage’s southern terminus and selling its parts for wood as was the norm at the time—the New Orleans simply reloaded and returned upriver. The feat was unprecedented. And in the decades since, modern ingenuity, such as quieter propulsion and the use of low-sulfur fuels, has resulted in such riverboats becoming a comfortable and luxurious way to see the country. These types of technological advancements are a trait that’s shared among all American Queen Voyages vessels, each with their own unique histories and stories to tell.

American Queen brought this kind of relaxing, slow-moving sojourn (“The average speed of our riverboat is three to five miles an hour,” says Rivera) back to life. When godmother Priscilla Presley christened the vessel in Memphis back in 2012, American river cruising was reborn.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0e/b6/0eb6c081-4e66-44c1-a9fc-7369f41c555d/americanqueen-aqsc_aq_grand_staircase_00138_1-v1.png)

Today, passengers can catch world-class entertainment in American Queen’s Grand Saloon, an exact replica of the Ford Theatre in Washington D.C.; browse a library of books in the Mark Twain Gallery, which boasts one of the country’s largest collections of Tiffany lamps; and enjoy a five-course dinner at the J.M. White Dining Room, a duplicate of the dining space on the palatial J.M. White, one of the most sumptuous river steamers ever built. Among the Queen’s most impressive historic features is her steam calliope: a glistening steam whistle organ with 37 gold-plated whistles that sing out in salute once the riverboat’s large red paddlewheel starts churning.

“It’s a throwback to a bygone era,” says Rivera, “Of course, the boat now includes excursions to riverside cities and towns as well.”

Onboard American Queen , guests can engage with a Mark Twain interpreter who brings history to life in the author and humorist himself, learn from naturalists and historians as they celebrate the river's many eras and landscapes, and hear talks given by Rivera himself, whose knowledge of river history and lore—from the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 to the stories behind old riverboat terms like “high-falootin” and “blowing your stack”—abounds.

The Queen’s sister vessels are equally as impressive. There’s the fleet’s newest jewel, American Countess , a sleek and bold contemporary paddlewheeler christened for sailing in 2020, and American Empress , the largest overnight riverboat west of the Mississippi. Passengers can delight in vast collections of intricate artifacts from Alaska Natives, Russia, the Gold Rush and the sternwheeler era; as well as culinary offerings inspired by the natural bounty of America’s Pacific Northwest.

“When you're traveling along the river you're still passing all these places that you wouldn't see otherwise,” says Rivera. “Riverboats give passengers the opportunity to get out and explore.”

American Queen Destinations

Over the course of its 9-day journey from Memphis to New Orleans (or reverse), American Queen makes stops at the lower Mississippi’s most charming ports-of-call.

Passengers boarding in Memphis are treated to a city steeped in history, from music—which includes the Memphis blues sound, the Blues Music Hall of Fame, and Elvis’ Graceland estate—to Civil Rights. In fact, its National Civil Rights Museum is built around the Lorraine Motel, the site of Martin Luther King Jr. 's 1968 assassination. For a deeper dive into Memphis as a whole, a visit to the city’s Beale Street Historic District is a must.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/a4/b1a4fd3f-3c7e-4b5c-9be9-286ce6ddac05/americanqueenvoyages-nationalcivilrightsmuseum-v1.png)

Disembarking in New Orleans, passengers can savor this spirited center of jazz, cultural fusion, and gourmet cuisine (think succulent seafood jambalaya and crawfish etouffee) at a pace all their own.

From exploring charming river towns where history comes alive to deeply discovering destinations through insightful enrichment, entertainment and regionally inspired cuisines, experience a truly transformative trip along America’s historic waterways with American Queen Voyages.

Where would you like to go? Find A Voyage

The Editorial Staff of Smithsonian magazine had no role in this content's preparation.

- Eat & Drink

- Arts & Design

- Health & Fitness

- Amy on the Go

A Walk Through the Historic Showboat Majestic Before It Left

I'd been running by the Showboat Majestic for years. Even long before those days of jogging along the riverfront, I'd noticed it. Despite all I had learned (and written) about Cincinnati history over the years, though, I never knew the boat was a floating theater until after the last curtain had been drawn.

Cincinnati is a city with a proud riverboat history—a place that idolizes that heritage at times. Tall Stacks came and went, along with several other paddle wheel-backed restaurants, but riverboat excursions and water taxis still operate between the Ohio and Kentucky riverfronts. There’s no denying that riverboats and their history are intrinsically linked with Cincinnati’s identity.

The Showboat wasn’t a steamship, though. In fact, it’s not necessarily a “ship” at all. It has no motor, no means of locomotion. An external means of conveyance, the towboat named Attaboy , once pushed it up and down American rivers. Since 1967, though, the floating theater was permanently moored on Cincinnati’s Public Landing.

SHOWBOATS (1800s-1920s)

Showboats were a tradition that can be traced back to 1816, when a cargo-carrying keelboat was repurposed as a means of transportation for a traveling theater troupe. The Floating Theatre was the first purpose-built showboat. Launching out of Pittsburgh in 1831, she kicked off a trend of vessels equipped with theaters that brought entertainment to communities scattered along the banks of rivers in the American frontier.

“Showboating” took a pause during the Civil War as the Union Navy sought to secure essential supply routes, but the tradition continued and expanded after the Confederacy’s surrender. Boats like the New Sensation, Goldenrod, Water Queen , and Princess proliferated a type of theater unique to American culture.

As the nation grew and the continent became connected, technology evolved and the showboat tradition began to diminish. Still, Captain Tom Reynolds (allegedly hailing from a showboat family himself) sought to ply the trade. The last ship he’d construct, the Majestic , launched from Pittsburgh in 1923. For years, Captain Reynolds lived on the boat with his family and used Attaboy to pilot the floating theater up and down Midwestern rivers. Often, he’d pull into a port and stay for a while when academic partnerships brought university students on board to perform.

THE MAJESTIC (1950s-2000s)

By 1959, Reynolds sold the ship to Indiana University. Although the school regularly used the historic vessel as a venue for productions, Captain Tom still maintained the boat. In December of that year, he was killed after being thrown from the tow ship Attaboy . It’s suspected that the boat’s engine “kicked.”

The United States Coast Guard would go on to usher in new regulations concerning wooden vessels. Majestic was pulled into dry dock and refitted with a steel hull. At the time, Indiana University also sought to sell the vessel. The City of Cincinnati outbid Louisville for the chance to place the boat on their riverfront.

Before stadiums and sprawling parks lined the riverbanks, the Showboat Majestic sat beneath a bridge off the shores of Cincinnati. A dedicated base of subscribers regularly patronized the floating theater to see productions put on by students from the University of Cincinnati. After the partnership with UC ended in 1988, a nonprofit known as Cincinnati Landmark Productions began producing shows on the boat. From 1991 to 2013, the company (who today operates the Covedale Center for the Performing Arts, Warsaw Federal Incline Theatre, and Cincinnati Young People’s Theatre) operated the boat’s 221-seat venue.

After they left, the City of Cincinnati began looking for a buyer.

Six years later, the city found one. A couple from Adams County, who had a reputation for preserving river history, purchased the ship for $110,000. They moved it in April of 2019 to a spot just west of Manchester. They hope to develop the boat into an upriver tourist and entertainment attraction and are currently working out plans to include crowdfunding a renovation.

After 52 years on the Cincinnati riverfront, the Showboat Majestic departed, but its legacy will float on.

You can lend your support to repurposing the Showboat Majestic at this GoFundMe pa ge. Follow more of author and photographer Ronny Salerno's work by visiting his website, Queen City Discovery.

- Do Not Sell or Share

- Cookie Preferences

River histories: a thematic review

- Published: 13 February 2017

- Volume 9 , pages 233–257, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- Paula Schönach ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8659-8012 1

1280 Accesses

13 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review discusses contemporary river history literature of the past two decades. It presents an introduction to the evolution of river history literature and discusses its relation to the scholarly field of environmental history. The review argues that the study of river histories is increasingly sophisticated methodologically, particularly in interdisciplinary breadth and comparative approaches. This article concentrates on selected studies of European and North American rivers during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and discusses the recent literature on river histories within three thematic frames. First, this paper discusses the spatial dimensions and different spatial scales of river histories, especially rivers as connectors and dividers. The second theme presents three different types of power relations in human–river interaction. Third, this paper will touch upon the temporal questions of river biographies. This review will pay special attention to the growing literature addressing the attempts to re-establish environmentally sound human–riverine relationships and improve the status of rivers through restorative activities. This article shows that a thematic analysis of contemporary river history offers a fruitful frame to understand the complex and intertwined nature of the temporal, spatial, and power-related dimensions in the narratives.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Ackroyd’s ( 2007 ) colossal and multi-layered work on the “sacred river” Thames serves as a European example, while Talbott’s ( 2009 ) piece on the Hudson River shows how the readership of river histories is widened to new audiences, children in this case.

Some monographs and edited volumes on river histories include more rigorous introductory or concluding chapters with reflections on conceptual and thematic choices and their methodological implications in the historiography (Mauch and Zeller 2008 ; Pritchard 2011 ; Castonguay and Evenden 2012a , b ; Coates 2013 ). But they draw mainly on the work presented in the edited volumes in question or the thematic subfield of the respective book.

I prefer the term field rather than discipline as a divergence from the institutional connotations of discipline . Scholarly field better includes the multiplicity of possible approaches and scholarly traditions applicable in environmental history, which, despite the flourishing scholarship, is still not an academically established discipline in many countries. See Huutoniemi et al. ( 2010 ). For the development of the field in general, see e.g. Hughes ( 2006 ).

This dynamism is reflected in the amount of non-western river history publications. As a key contribution, Volume 1 in the Water History Series (Eds. Tvedt and Jakobsson 2006a ) offers an extensive selection of river history cases from all inhabited continents, and predominantly from the non-western world. For the Latin American perspective, see Cleary ( 2001 ) for a review of the environmental history of the Amazon.

The main sources have been the major journals in the field, Water History, Environmental History, and Environment & History. While the thematic foci of this paper guided the choice of monographs for the analysis, it was to some degree influenced by the significance of some works within the field, indicated by citations, and occasionally limited due to resources and availability. Additionally, I have included some works published in less common languages (Finnish and Swedish).

For the sake of clarity, I use river as an overarching term, including main rivers, tributaries, and smaller creeks as well, while being aware that river terminology is variable and differently defined according to linguistic, scientific, or historical contexts. The appropriate terms may vary by the discharge of the river, the navigability of the river, the size of its catchment area, its geographical location (e.g. in the Swedish language rivers north of the Göta älv and Dalälven are called älv, south of them å or ström, and rivers outside of Scandinavia are called flod ), or other criteria.

European scholars with their linguistic diversity balance local significance and audience and international accessibility to their research against international academic publishing with an English language dominance. Since article-length contributions can cover only a very small and specific part of river history, terming them “environmental history of river X”, which implies comprehensive coverage of complex histories, may seem inaccurate to scholars. Special journal issues focusing on one river and successfully exemplified by the “Danube-issue” of Water History (Vol 5, issue 2, 2013), proves to be one recommendable alternative to bridge these challenges.

I use the term interdisciplinarity as an overarching term for different kinds of research activities that include at least two research fields, in whatever degree of interaction and relatedness, and I will not elaborate on the distinct conceptualizations of interdisciplinarity (e.g. multidisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity, etc.) See Huutoniemi et al. ( 2010 ). For a discussion on the possibilities and challenges of interdisciplinarity in environmental history see Hamilton et al. ( 2011 ).

These are based on typologies for the field of environmental history as presented by Massa ( 1991 ), McNeill ( 2003 ), and Mosley ( 2010 ).

Massa ( 1991 ) classifies the political sphere as a distinct, fourth category that also includes changes in the institutional structures.

Henshaw ( 2011 ) used the term “River of Inspiration” in his work on the Hudson River somewhat earlier but lacked more detailed elaboration on the nature of this “inspiration”.

Science, Technology and Society-studies, which itself is an interdisciplinary subject.

Special Issue of Water History Vol 5, issue 2 ( 2013 ).

Developed by urban environmental historian Tarr ( 2002 ), and applied by e.g. Barles ( 2007 , 2012 ) for the Seine study and Gierlinger et al. ( 2013 ) for the Danube.

In a rare example from non-western rivers, Hoag ( 2013 ) uses the insights from several African rivers (Rufiji, Gambia, Volta, Niger) to explore and explain continuities in African development and the related colonial legacies.

The adjacent articles on each case comprise a special edition of Water History 8(3):2016.

Several histories of earlier periods show that human induced alterations of riverine environments are by no means an invention of the late modern period nor exclusive to the North American or European spheres (see Wilson 2010 ; Hoffmann 2010 ). However, the scale and geographical extent of human activity constitute a landmark of the modern exploitation of rivers.

While the issue of cooling water used for the generation of electricity has been addressed by some scholars (e.g., White 1995 , p. 81; Pritchard 2011 ), it has so far remained a somewhat neglected topic in environmental river histories.

She credits Steinberg’s ( 1991 ) work for influence in the development of the concept.

A panel at the congress of the American Society for Environmental History in 2014 was titled ‘Rivers with bad habits’.

See special issue of Environment and History 19 (2), 2013.

See also Reuss and Cutcliffe ( 2010 ).

For an introduction to the roots and differences of historical environmental justice scholarship, see Massard-Guilbaud and Rodger 2011 ). Questions of justice has resonated in river history scholarship as well, and the perspective of the less-powerful in these struggles has become more present in the narratives. This is a significant theme in river histories of the non-western world, as well, as colonial legacies remain influential in present day challenges.

With the exception of Mark Cioc’s “Eco-Biography of the Rhine” ( 2002 ), scholars have passed over specifying what they mean, or what temporal specifications they attribute to ‘river biography.’ See the section entitled “River biographies” in Tvedt and Jakobsson ( 2006a , b ), where river biography as a term is neither introduced by the editors nor by the individual contributors; see also Coates ( 2013 , p. 86).

From a practical point of view, sudden exceptional events are also often the historical repositories of evidence and important source bases for the analysis.

Jakobsson ( 2008 , pp. 55–56) see the references for examples.

This critique concerns the field of environmental history. See e.g. McNeill ( 2003 , p. 35).

This is an important feature in non-western river historiography as highlighted by Hoag ( 2013 ) in a study on African rivers. The many sides of river management to development of the global South is a topical theme.

The Big Dam Era is often said to have started with the construction of the Hoover Dam (early 1930s) and it depicts the construction boom of large dams in North America, which lasted until the second half of the twentieth century (see e.g. Melosi 2011 for more). The (global) history of damming rivers is a vast and complex field as such, and deserves its own review.

I refrain from labeling the current time as post-industrial since, despite some shifts in emphasis, industrial production and the exploitative use of rivers remains a backbone of economic success in the global north.

For the historical baseline problem of ecological restoration in general, see e.g. Hall ( 2005 ).

McCool ( 2010 , pp. 281–282). This also comes close to Pritchard ( 2011 ) emphasis on “light-green” efforts to reconcile technology and nature.

Environmental history has been found to be to single most increased sub-field within history during the past 4 decades, see http://historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/december-2015/the-rise-and-decline-of-history-specializations-over-the-past-40-years .

Ackroyd P (2007) Thames: sacred river. Chatto & Windus, London

Google Scholar

Armstrong C, Evenden M, Nelles HV (2009) The river returns: an environmental history of the bow. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal

Backouche I (2008) From Parisian river to national waterway: the social functions of the Seine, 1750–1850. In: Mauch C, Zeller T (eds) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 26–40

Bagle E (2012) An urban industrial river: the multiple uses of the Akerselva river, 1850–1900. In: Castonguay S, Evenden M (eds) Urban rivers: remaking rivers, cities, and space in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 57–74

Barles S (2007) Urban metabolism and river systems: an historical perspective—Paris and the Seine, 1790–1970. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 11(6):1757–1769

Article Google Scholar

Barles S (2012) The Seine and Parisian metabolism: growth of capital dependencies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In: Castonguay S, Evenden M (eds) Urban rivers: remaking rivers, cities, and space in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 95–112

Berg R, Jakobsson E (2006) Nature and diplomacy: the struggle over the scandinavian border rivers in 1905. Scand J Hist 31(3–4):270–289. doi: 10.1080/03468750600930795

Blackbourn D (2006) The conquest of nature: water, landscape, and the making of modern Germany, 1st American edn. Norton, New York

Blackbourn D (2008) “Time is a violent torrent”: constructing and reconstructing rivers in modern German history. In: Mauch C, Zeller T (eds) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 11–25

Bonnell JL (2014) Reclaiming the don: an environmental history of Toronto’s Don River Valley. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Carse A (2012) Nature as infrastructure: making and managing the Panama Canal watershed. Soc Stud Sci 42(4):539–563

Castonguay S, Evenden M (2012a) Introduction. In: Castonguay S, Evenden M (eds) Urban rivers: remaking rivers, cities, and space in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 1–13

Castonguay S, Evenden M (2012b) Conclusion. In: Castonguay S, Evenden M (eds) Urban rivers: remaking rivers, cities, and space in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 237–242

Cioc M (2002) The Rhine: an eco-biography, 1815–2000. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Cleary D (2001) Towards an environmental history of the Amazon: from prehistory to the nineteenth century. Lat Am Res Rev 36(2):65–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2692088

Closman CE (2008) Holding the line: pollution, power, and rivers in Yorkshire and the Ruhr, 1850–1990. In: Mauch C, Zeller T (eds) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 89–109

Coates P (2013) A story of six rivers: history, culture and ecology. Reaktion Books, London

Collins TM, Muller EK, Tarr JA (2008) Pittsburgh’s three rivers: from industrial infrastructure to environmental asset. In: Mauch C, Zeller T (eds) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 41–62

Cooke GD (2005) Restoration and management of lakes and reservoirs, 3rd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Cronon W (1992) A place for stories: nature, history, and narrative. J Am Hist 78(4):1347–1376

Cusack T (2010) Riverscapes and national identities, Kindle-edition. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse

Deligne C (2012) Brussels and its Rivers, 1770–1880: reshaping an urban landscape. In: Castonguay S, Evenden M (eds) Urban rivers: remaking rivers, cities, and space in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 17–33

Doyle M, Havick DG (2009) Infrastructure and the environment. Annu Rev Environ Resour 34:349–373

Evenden M (2004) Fish versus power: an environmental history of the Fraser River. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Evenden M (2015) Allied power: mobilizing hydroelectricity during Canada’s Second World War. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Fougeres D (2011) Surface water in the early nineteenth century. In: Castonguay S, Dagenais M (eds) Metropolitan natures: environmental histories of Montreal. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 85–100

Garcier RJ (2007) Rivers we can’t bring ourselves to clean—historical insights into the pollution of the Moselle River (France), 1850–2000. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 11(6):1731–1745. doi: 10.5194/hess-11-1731-2007

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gierlinger S, Haidvogl G, Gingrich S, Krausmann F (2013) Feeding and cleaning the city: the role of urban waterscape in provision and disposal in Vienna during the industrial transformation. Water Hist 5(2):219–239

Graham S, Marvin S (2001) Splintering urbanism: networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. Routledge, London

Gumbrecht B (2000) The Los Angeles river: its life, death, and possible rebirth, Paperback edn. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Hall M (2005) Earth repair: a transatlantic history of environmental restoration. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville

Hamilton A, Watson F, Davies AL, Hanley N (2011) Interdisciplinary conversations: the collective model. In: Sörlin S, Warde P (eds) Nature’s end: history and the environment, Paperback edn. Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, pp 162–187

Hasenöhrl U (2008) Postwar perceptions of German rivers: a study of the lech as energy source, nature preserve, and tourist attraction. In: Mauch C, Zeller T (eds) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 137–148

Henshaw RE, Dunwell F (eds) (2011) Environmental history of the Hudson River: human uses that changed the ecology, ecology that changed human uses. State University of New York Press, New York

Hoag H (2013) Developing the rivers of east and west Africa: an environmental history. Bloomsbury Academic, London

Hoffmann RC (2010) Elemental resources and aquatic ecosystems: medieval europeans and their rivers. In: Tvedt T, Coopey R (eds) A history of water: vol 2, Rivers and society: from early civilizations to modern times, I.B. Tauris, London, pp 165-202

Hohensinner S, Jungwirth M (2016) The unknown third dimension: terrain elevations, water depths and fluvial dynamics of Austrian Danube river landscapes prior to regulation. Österreichische wasser- abfallwirtschaft 68(7):324–341. doi: 10.1007/s00506-016-0323-6

Hohensinner S, Sonnlechner C, Schmid M, Winiwarter V (2013) Two steps back, one step forward: reconstructing the dynamic Danube riverscape under human influence in Vienna. Water Hist 5(2):121–143. doi: 10.1007/s12685-013-0076-0

Hughes JD (2006) What is environmental history? Polity Press, Cambridge

Huutoniemi K, Klein JT, Bruun H, Hukkinen J (2010) Analyzing interdisciplinarity: typology and indicators. Res Policy 39(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2009.09.011

Jakobsson E (1996) Industrialisering av älvar: Studier kring svensk vattenkraftutbyggnad 1900–1918. Dissertation, Historiska Institutionen i Göteborg

Jakobsson E (2002) Industrialization of rivers: A water system approach to hydropower development. Knowl, Technol Policy, 14(4), 41. Retrieved from http://www.search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=7707533&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Jakobsson E (2008) Narratives about the river and the dam. In: Seminarrapport Utstein Kloster (ed) Technological society—multidisciplinary and long-time perspectives, Haugaland Akadem, Haugaland, pp 53–61

Kelman A (2006) A river and its city: the nature of landscape in New Orleans, 2nd edn. University of California Press, Berkley

Kibel PS (ed) (2007) Rivertown: rethinking urban rivers. MIT Press, Cambridge

Kinnersley D (1988) Troubled water: rivers, politics and pollution. Hilary Shipman Ltd., London

Korjonen-Kuusipuro K (2011) Critical water: negotiating the Vuoksi river in 1940. Water Hist 3(3):169–186. doi: 10.1007/s12685-011-0035-6

Korjonen-Kuusipuro K (2012) Yhteinen Vuoksi: Ihmisen ja ympäristön kulttuurinen vuorovaikutus Vuoksen jokilaaksossa 1800-luvulta nykypäiviin. Dissertation, Oulun yliopisto

Korjonen-Kuusipuro K, Kohvakka M (2010) Vuoksi historiallisena tilana. Hist Aikak 108(1):73–84

Lehmkuhl U (2007) Historicizing nature: time and space in German and American environmental historiography. In: Lehmkuhl U, Wellenreuther H (eds) Historians and nature: comparative approaches to environmental history, The Krefeld Historical Symposia edn. Berg, Oxford, pp 17–44

Lübken U (2012) Rivers and risk in the city: the urban floodplain as a contested space. In: Castonguay S, Evenden M (eds) Urban rivers: remaking rivers, cities, and space in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 130–144

Lübken U (2014) Die natur der gefahr: überschwemmungen am Ohio River im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, Göttingen

Luckin B (2001) Pollution in the city. In: Daunton M (ed) Cambridge urban history of Britain, volume 3, 1849–1950, Online edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 207–228

Chapter Google Scholar

MacFarlane D (2014) Negotiating a river: Canada, the US, and the creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway. UBC Press, Vancouver

Massa I (1991) Ympäristöhistoria tutkimuskohteena. Hist Aikak 98(4):294–301

Massard-Guildbaud G (forthcoming) The city whose rivers disappeared. Nantes, 1850–1950. In: Schott D, Knoll M, Lübken U (eds) Cities and rivers. Historical interactions. Pittsburgh University Press, Pittsburgh

Massard-Guilbaud G, Rodger R (2011) Reconsidering justice in past cities: when environmental and social dimensions meet. In: Massard-Guilbaud G, Rodger R (eds) Environmental and social justice in the city: historical perspectives. White Horse Press, Cambridge, pp 1–40

Mauch C, Zeller T (2008) Rivers in history and historiography: an introduction. In: Mauch C, Zeller T (eds) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 1–10

McCool D (2010) Implementing river restoration projects. In: Hall M (ed) Restoration and history: the search for a usable environmental past. Routledge, New York, pp 275–283

McCool D (2012) River republic: the fall and rise of America’s rivers. Columbia University Press, New York

McCully P (2001) Silenced Rivers: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams. Enl. and updated edn., Zed, London.

McNeill JR (2003) Observations on the nature and culture of environmental history. Hist Theory 42:5–43

Melosi MV (2011) Precious commodity: providing water for America’s cities. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh

Morris C (2012) The big muddy: an environmental history of the Mississippi and its peoples from Hernando de Soto to Hurricane Katrina. Oxford University Press, New York

Mosley S (2010) The environment in world history. Routledge, Abingdon

Pawson E, Dovers S (2003) Environmental history and the challenges of interdisciplinarity: an Antipodean perspective. Environ Hist 9(1):53–75

Pritchard SB (2011) Confluence: the nature of technology and the remaking of the Rhône. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Pritchard SB, Zeller T (2010) The nature of industrialization. In: Reuss M, Cutcliffe SH (eds) The illusory boundary: environment and technology in history. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, pp 69–100

Reuss M, Cutcliffe SH (2010) Introduction. In: Reuss M, Cutcliffe SH (eds) The illusory boundary: environment and technology in history. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, pp 1–6

Ritter C (1865) Comparative geography (transl. Gage WL ed) J.B. Lippincott & Co, Philadelphia

Rosenberg E (2015) Water infrastructure and community building: the case of Marvin Gaye park. J Urban Des 20(2):193–211. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2015.1009011

Rueck D (2011) When bridges become barriers: montreal and kahnawake mohawk territory. In: Castonguay S, Dagenais M (eds) Metropolitan natures: environmental histories of Montreal. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 228–244

Russell E, Tucker RP (2004) Introduction. In: Tucker R, Russell E (eds) Natural enemy, natural ally: toward an environmental history of Warfare. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, pp 1–14

Saikku M (2005) This delta, this land: an environmental history of the Yazoo-Mississippi floodplain. University of Georgia Press, Athens

Schneer J (2005) The Thames. Yale University Press, New Haven

Schönach P (2004) Saippuakuplista suojeluun: Vantaanjoen ympäristöhistoriaa 1945–1963. Tutkimuskatsauksia 6. Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus, Helsinki

Schönach P (2015) Expanding sanitary infrastructure and the shaping of river history: River Vantaa (Finland), 1876–1982. Environ Hist 21(2):201–226

Showers KB (2009) Congo River’s Grand Inga hydroelectricity scheme: linking environmental history, policy and impact. Water Hist 1(1):31–58. doi: 10.1007/s12685-009-0001-8

Steinberg T (1991) Nature incorporated: industrialization and the waters of New England. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Summitt AR (2013) Contested waters: an environmental history of the Colorado river. University Press of Colorado, Boulder

Swyngedouw E (2004) Social power and the urbanization of water: flows of power. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Swyngedouw E (2015) Liquid power: contested hydro-modernities in twentieth-century Spain. MIT Press, Cambridge

Talbott H (2009) River of dreams: the story of the Hudson River. G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers, New York

Tarr JA (2002) The metabolism of the industrial city: the case of Pittsburgh. J Urban Hist 28(5):511–545

Tarr JA (2010) The city as an artifact of technology and the environment. In: Reuss M, Cutcliffe SH (eds) The illusory boundary: environment and technology in history. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, pp 145–170

Tvedt T (2004) The River Nile in the age of the British: political ecology and the quest for economic power. I. B Tauris, London

Tvedt T, Coopey R (2010) A ‘water systems’ perspective on history. In: Tvedt T, Coopey R (eds) A history of water: vol 2, Rivers and society: from early civilizations to modern times, I.B. Tauris, London, pp 3-26

Tvedt T, Jakobsson E (2006a) Introducttion: water history is world history. In: Tvedt T, Jakobsson E (eds) A history of water: volume 1: water control and river biographies. I.B. Tauris, London, pp ix–xxiii

Tvedt T, Jakobsson E (2006b) A history of water: volume 1: water control and river biographies. I. B. Tauris, London

Tvedt T, Oestgaard T (2006) Introduction. In: Tvedt T, Oestgaard T (eds) A history of water. volume 3: the world of water. I.B. Tauris, London, pp ix–xxii

Uekötter F (2007) Enzyklopädie deutscher geschichte. bd. 81, umweltgeschichte im 19. und 20. jahrhundert. Oldenbourg, Münch

van Dam P, Verstegen SW (2009) Environmental history: object of study and methodology. In: Boersma JJ, Reijnders L (eds) Principles of environmental sciences. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 25–31

Warren LS (2003) Introduction. In: Warren LS (ed) American environmental history. Blackwell, Malden, pp 1–3

White R (1995) The organic machine: the remaking of the Columbia River. Hill and Wang, New York

Williams JC (2010) Understanding the place of humans in nature. In: Reuss M, Cutcliffe SH (eds) The illusory boundary: environment and technology in history. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, pp 9–25

Wilson RI (2010) Changing river regimes on the Kanto Plain, Japan, 1600–1900. In: Tvedt T, Coopey R (eds) A history of water, vol 2, Rivers and society: from early civilizations to modern times, I.B. Tauris, London, pp. 287–311

Winiwarter V, Schmid M, Hohensinner S, Haidvogl G (2013) The environmental history of the Danube river basin as an issue of long-term socio-ecological research. In: Singh SJ, Haberl H, Chertow M, Mirtl M, Schmid M (eds) Long term socio-ecological research: studies in society-nature interactions across spatial and temporal scales. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 103–122. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-1177-8_5

Winiwarter V, Haidvogl G, Hohensinner S, Hauer F, Bürkner M (2016) The long-term evolution of urban waters and their nineteenth century transformation in European cities. A comparative environmental history. Water Hist 8(3):209–233. doi: 10.1007/s12685-016-0172-z

Worster D (1985) Rivers of empire: water, aridity and the growth of the American West. Pantheon Books, New York

Zeisler-Vralsted D (2008) The cultural and hydrological development of the Mississippi and Volga rivers. In: Mauch C, Zeller T (eds) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 63–77

Zeisler-Vralsted D (2015) Rivers, memory, and nation-building: a history of the Volga and Mississippi rivers. Berghahn Books, New York

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Helsinki University Centre for Environment (Multidom-project) and the Academy of Finland (Grant Nos. 263305 and 286676).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, PO Box 65, 00014, Helsinki, Finland

Paula Schönach

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paula Schönach .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Schönach, P. River histories: a thematic review. Water Hist 9 , 233–257 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12685-016-0188-4

Download citation

Received : 17 May 2016

Accepted : 09 November 2016

Published : 13 February 2017

Issue Date : September 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12685-016-0188-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- River history

- Environmental history

- Nineteenth and twentieth century

- North America

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Mississippi River

Mississippi River History

St. Paul and Minneapolis exist today because of riverboats. In fact, virtually every city along the major rivers of the United States can trace its very existence to the arrival of riverboats in America. In the early 1800s, the Minnesota Territory was inhabited by Native Americans, soldiers, trappers, traders, explorers, and lumbermen. The cities, if you could call them that, were little more than camps where these rugged individuals congregated to drink, play cards, fight, and rest.

Native Americans hunted and farmed in the Mississippi valley for hundreds of years before white men arrived. The first European settlement in the Twin Cities area was Fort Snelling. In 1805, President Thomas Jefferson sent a young army Lieutenant, Zebulon Pike, into the area to find a suitable site to build a military outpost. Two years earlier, President Jefferson had purchased the entire central portion of the country from the Canadian border to the Gulf of Mexico from Napoleon Bonaparte of France. That land agreement was called the Louisiana Purchase. President Jefferson wanted an army post in Minnesota to protect the country’s new land from the British and to keep the peace between warring Indian nations—the Dakota and Ojibway.

Lt. Zebulon Pike

Arriving at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers in the summer of 1805, Lt. Pike met French-Canadian Fur Trader Jean Baptiste Faribault repairing his canoe at the lower end of the island. After exploring the area, Pike determined that the bluffs overlooking the island between the two rivers would be an excellent location for the fort. That island eventually was named Pike Island, in his honor.

Col. Josiah Snelling

Fourteen years later, the first contingent of soldiers, led by Col. Henry Leavenworth, arrived to begin construction of the fort, originally called Fort St. Anthony. They endured extreme hardships in the first year, and nearly 40 men died over the winter. A new commander, Col. Josiah Snelling, took charge in 1820 and over the next four years, he supervised construction. Upon completion of the new military complex, Gen. Winfield Scott came from Washington D.C. to inspect the fort. He was so impressed with what Snelling and his men had accomplished in the wilderness that he recommended to Congress that they rename the facility Fort Snelling.

A Place Called Pig’s Eye

In the 1830s, a rugged frontiersman came to the Minnesota Territory. Known as Pig’s Eye Parrant because of a battered face he had acquired as a result of too many barroom brawls, the bawdy newcomer discovered a cave on the north bank of the Mississippi River about four miles downriver from Fort Snelling. In the cave was a marvelous, spring-fed stream; thus, given the name Fountain Cave. Ole Pig’s Eye, who brewed liquor, decided that Fountain Cave was a perfect place for his home and business. He quickly found many customers at Fort Snelling.

Over the years, a number of civilians had migrated down from Canada and settled on the government land surrounding Fort Snelling. By 1838, the new commandant became concerned with the growing civilian population at the Fort. He told them to leave Fort property, and when they refused, he ordered his troops into their settlement. The soldiers forced the civilians out of the area and burned their homes. There was no other white settlement for hundreds of miles, so 150 families wandered down the river until they came to Pig’s Eye Cave. Fresh water, unlimited hunting and fishing, and a ready supply of lumber made the cave a perfect place to live. The people formed a new community, and they called it Pig’s Eye.

Three years later, in 1841, a Catholic priest named Father Lucien Galtier arrived and built a small log chapel about a mile downstream (near the present site of the Robert Street Bridge). Every Sunday, the people of the Pig’s Eye community traveled down river to Father Galtier’s chapel. Soon, they became dissatisfied with the name of the community and decided to change it to the name of that little chapel. It was the Chapel of Saint Paul. That is how the city of St. Paul began at Fountain Cave, which was located approximately where the ADM Grain Terminal is today along Shepherd Road, just upriver from the downtown area.

Riverboats Create St. Paul

Over the next few years, the tiny community grew slowly until the big riverboats suddenly began to venture north on the Mississippi River. Please remember, there were no cars, trucks, trains, or airplanes. Travel was done through the woods by walking, riding a horse, in a wagon pulled by horse/oxen, or by boat. Rivers were the “freeways” of the 1800s. Travel was faster and much more comfortable on the big riverboats than by any other means. By the 1850s, hundreds of riverboats were coming to St. Paul bringing all types of goods and thousands of people. The entire Minnesota Territory had a non-Indian population of about 6,000 people in 1850. By the early 1860s, the population had exploded to 200,000. Almost all of those new residents arrived by riverboat.

Riverboat traffic began modestly in 1847 with 47 vessels arriving in Saint Paul—including the riverboat Lynx with a 23-year-old school teacher named Harriet Bishop. Riverboat arrivals increased each year, attaining peaks of 1,027 in 1857 and 1,068 in 1858 (the year Minnesota became a state). Severe national economic depression struck in 1859, slashing riverboat arrivals to 808. Arrivals held relatively steady into the 1860s, when the Civil War dominated national attention. During the war, many riverboats transported military troops and supplies throughout the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Some were even converted to early battleships using bales of cotton stacked high around their perimeters to defend against hostile gunfire. As the war ended, steel rails were being laid across the country, and riverboat landings in St. Paul plummeted almost to extinction.

You can see that riverboats truly did play a vital role in the creation of St. Paul. However, as marvelous as these big boats were, they posed many serious threats. In those early days, riverboats were powered by giant steam engines. Steam engines used wood that was in abundant supply along the river shores for fuel. Unfortunately, steam engines were under tremendous pressure, and the boilers frequently exploded, destroying the riverboat and killing many passengers and crew. Another danger was fire that could be started by hot sparks, which billowed out of the riverboat’s smokestacks. If the riverboat somehow managed to avoid fire and explosion, they also faced peril from rocks and snags (dead trees) under the water that could puncture the wooden hull and sink the boat.

Traveling the river was a very dangerous experience but one that many people made in the hope of reaching this new land of lush woods and abundant wildlife. Just to prove that human beings are not totally without hope, we did learn from those early mistakes. Today, riverboat travel is extremely safe due to the upgrades that have been made in vessel construction, course plotting, river maintenance, and crew training.

* All historic paintings are from the private collection of Capt. William D. Bowell, Sr., founder of the Padelford Packet Boat Co., Inc. The paintings were done by Padelford employee Ken Fox.

Gift Certificates, Season Passes & Promotions

Gift Certificates

Buy Online, Redeem Online

Special Offers

Family Season Passes

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Padelford Riverboats 205 DR Justus Ohage Blvd. Harriet Island St. Paul, MN 55107

LOCAL: 651-227-1100

10 Surprising Facts About St. Patrick’s Day

S t. Patrick’s Day on March 17 is often marked in the U.S. by quirky traditions, such as Chicago dyeing its river emerald green , but the holiday has historical and religious roots in its origin country of Ireland.

Here are 10 surprising facts you may not have known about how St. Patrick’s Day started, its legendary symbols, and how it’s still celebrated today.

St. Patrick’s Day’s namesake was not born Irish

People often wonder: “What is the true story of St. Patrick’s Day?” The holiday is named after St. Patrick, a Patron Saint of Ireland, who died around the fifth century.

However, St. Patrick is thought to have been a Roman citizen in Britain who was enslaved and taken to Ireland, either escaped or was released, then returned as a priest and converted Druids to Christianity, Marion Casey, a clinical assistant professor of Irish Studies at New York University, previously told TIME.

If you have also found yourself querying, “Why do we celebrate St. Patrick’s Day on March 17?” it’s because that is believed to be the day that he died.

St. Patrick’s Day began as a Catholic Feast Day

If you’re ever asked, “What is St. Patrick’s Day celebrated for?” it was originally started in 1631 by the Catholic Church as a Feast Day honoring St. Patrick—one of many church holidays.

However, the holiday, imported to the U.S. by Irish immigrants, morphed into a show of Irish-American pride and worldwide celebration of Irish culture.

Legend says St. Patrick used the shamrock to teach Christianity

Legend has it that St. Patrick used the shamrock, a three-leaf clover, to teach the Christian doctrine of the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in one. Irish botanist and cleric Caleb Threlkeld described the connection in 1726, when he also wrote that the shamrock was the emblem of the holiday and the country’s national symbol.

However, historians say the story is likely fiction, as the plant itself is mythical and not linked to a scientific species , according to National Geographic. The shamrock became associated more broadly with Ireland as a symbol during rebellions against Britain in the 18th century.

Green became connected to St. Patrick’s Day after Irish rebellions

Green as an Irish color has political origins. Timothy McMahon, Vice President of the American Conference for Irish Studies, previously told TIME the color dates back to the Great Irish Rebellion of 1641 , where Catholic local leaders revolted against the English crown, using a green flag with a harp as an emblem.

Green was worn again during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 . The Irish forces promoted the nationalistic ballad “ The Wearing of the Green, ” which immortalized the color’s connection with Ireland.