Home » American History » How Riverboats and Steamers Shaped American History

How Riverboats and Steamers Shaped American History

Before trains and automobiles, it was riverboats that connected America. You can learn more about the rich American tradition of steamships here.

Throughout American history, there have been many modes of transport that forever changed the face of this country. Everything from the development of automobiles to the railroad, canal boats, and even the covered wagon—they’ve all played a big role in bringing us to where we are today.

The steamboat is part of this rich history. While there are lots of different types of steamboats, some of which are ocean going, we’ll focus on the riverboat variety here. Prior to automobiles and railways, it was rivers that connected one part of the U.S. to another. Steamboats were responsible for ferrying people and goods all over the country and to the coasts where shipments could then be transported overseas. Let’s jump in and start with the earliest known steamboat history.

Steamboats Invented in Europe

Though these boats were responsible for reshaping America, they were originally developed in Europe. You see, it was in the late 1600s when early experiments on the steam engine began. These were led by the French inventor Denis Papin, and Thomas Newcomen of England. It started with a device known as the steam digester, which was an early kind of pressure cooker. From there, these two men experimented with pistons, and Papin eventually suggested that this technology could be used to operate a paddlewheel boat.

Both men made designs attempting to power a boat, though neither of their designs worked that well. Still, innovation is part of the human spirit, so soon, other inventors followed suit. English scientist John Allen patented the first steamboat in 1729. Over the next thirty-some years, other inventors attempted to improve on steam engines and steamboats, one of whom was William Henry from Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He produced his own steam engine in 1763, which he put on a boat. The boat sank—but it’s thought perhaps Henry’s work inspired others to keep innovating.

The Rise of Steamboats in America

From there, it was a race to develop working steam engines—and working steamboats. Several people made working steamboats in the 1780s. In the United States, John Fitch of Philadelphia launched a steamboat in 1787, and it proved such a success that by 1788, he was operating a commercial steamboat service that followed the Delaware River between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey . This was a passenger boat that could carry up to 30 people, traveling between seven and eight miles per hour.

Unfortunately for Fitch, while his boat was a success, his business was not. The route on which his boat traveled was one already well covered by roads and wagons, so there wasn’t much need for a passenger boat.

But later, Robert Fulton, an American inventor who found himself intrigued by the possibilities of steamboats, ended up creating his own vessel in 1807. This was the North River Steamboat , which later became known as the Clermont —and it could be considered the boat that started the steamship revolution in the U.S.

The Clermont was pretty incredible for the time. It traveled the Hudson River between New York City and Albany, making the 150-mile trip in as little as 32 hours. Because of its capabilities, it became the first commercially successful steamboat in the U.S.

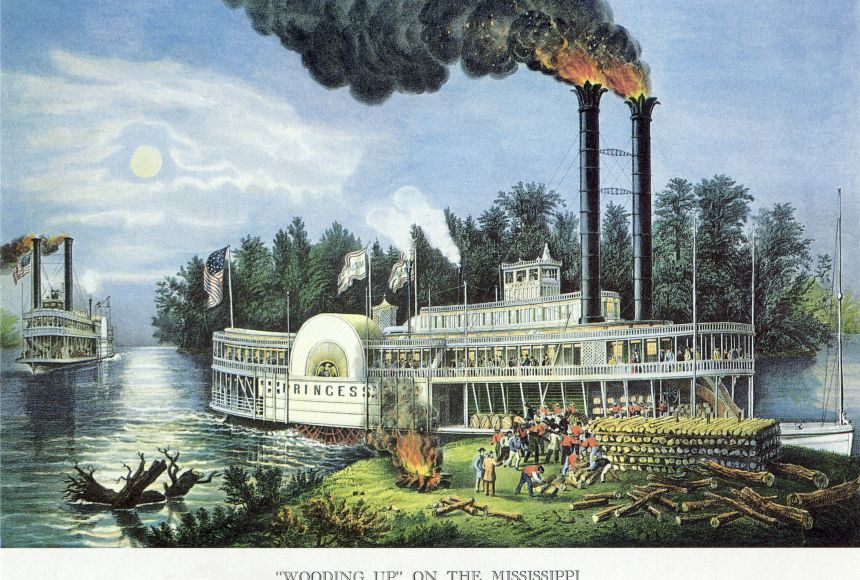

In the wake of the Clermont’s success, steamboats began to proliferate around the United States—especially along the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, where they were instrumental in not only ferrying passengers up and down long stretches but also hauling grain, lumber, supplies or anything else that needed to be moved long distances. These riverboats also grew in prominence in the western United States during the California Gold Rush, usually pressed into service to carry miners and mining supplies closer to the gold fields.

Riverboats During the Civil War

When you hear about Civil War boats, the two that most people are familiar with are the Monitor and the Merrimack , which were ocean-faring steamships called “ironclads.” They receive most of the historical attention because truly, these two ships were a revolution of their times. But there’s a whole other side to Civil War naval history that you don’t often hear about—and that was the battles waged by Union and Confederate riverboats.

Away from the East Coast, the naval war was fought for control of the major rivers, most especially the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers—and this involved paddlewheel boats that had been converted into warships. These river battles were waged by monitors, which were heavily armed but lightly armored smaller rivercraft, and ironclads, which were boats that had been heavily armored with iron plates. Some of the war’s most famous battles, like the Battle of Vicksburg, involved the use of riverboats. Between the Vicksburg battle and the seizure of New Orleans, this secured the Mississippi River for the Union Army, enabling them to transport men and supplies up and down the river.

The Heyday of America’s Greatest Riverboats

To this day, the Mississippi River is still a major shipping lane within the United States, though nowadays, you’ll find a variety of craft going up and down its waters. Through the 19 th century to the early parts of the 20 th century, however, it was the paddlewheel steamer that dominated the Mississippi—and other major rivers, too. Some of these boats were so famous that they became state symbols, like the Iowa , which was an 1838 steamer that is part of Iowa’s state seal. The Anson Northup is another famous steamer that in 1859, became the first to cross over from the U.S. to Canada on the Red River.

During this time, steamers were a major part of what drove American expansion. Their speed and power meant that people could transport more goods and passengers than ever before, which is a big part of the reason why port towns flourished so well—because steamers were bringing in the goods from the heartlands that would be transported for trade overseas. These rivercraft became iconic, something that people all over the United States took great pride in as symbols of progress and prosperity.

Eventually, though, riverboats began to wane in popularity. There were a couple of reasons behind this. For one thing, the big steamers were incredibly dangerous. Ultimately, most of these boats would either burn down or they’d be destroyed when the powerful boilers that powered them exploded. They were wooden ships, after all, powered largely by wood fires since wood was so easy to procure along the rivers on which they ran. Accidents were quite frequent, and many who traveled on them took their lives into their own hands. In places like Alton, Illinois, homes along the river even featured platforms called “widow’s walks,” which were rooftop platforms where women would watch for their husbands to come home on the riverboats they crewed. To put into perspective how dangerous these crafts were, the Scientific American reported in December 1860 that 487 people had died that year in steamboat accidents.

Even though steamers were dangerous, the danger wasn’t the primary factor behind their decline. Actually, it was the development of the railroad. As more and more rail lines began to spread across the United States, riverboat popularity waned. Railroads had too many advantages—they were faster, capable of hauling more, they were safer, and they could reach landlocked places that didn’t have river access.

Even so, riverboats never did go out of service entirely. Today, you’ll still find them all over America’s largest rivers. Some of those old paddle steamers that were once so iconic are still around, though these days, most are replica pleasure craft designed with modern engines that are infinitely safer than the old wood-fired boilers that used to run them.

Riverboats are still a rich American tradition, and they truly were a formative part of American history. If you ever have the opportunity, schedule a cruise or even an afternoon tour on one of America’s replica paddleboats. It’s an experience that will take you back in time.

You may also like

Echoes of Time: The Living Legacy of Old Fort Niagara

Bob Waldmire: The Free Spirit of Route 66

The Birth of Prosthetics

Cleveland’s Man of Steel

A Beacon of History on Lake Ontario

How Martin Luther King Jr. Day Became a Federal Holiday

Will founded Ancestral Findings in 1995 and has been assisting researchers for over 25 years to reunite them with their ancestors.

In their golden age, riverboats were our nightclubs, our theater district, our parade ground

A look back at the history of the Mississippi River

by Jeannette Cooperman

June 8, 2011

Photograph courtesy of Ed Lekosky

Sometimes it seems like all we know of the river is fireworks and gambling. And floods. But in the late 1800s, there could be as many as 1,200 steamboats out on the river at once. Instead of a banquet at a stuffy hotel, a fundraiser might be a moonlit cruise on the Charles P. Chouteau side-wheeler. Orphans were taken on “fresh-air excursions”; courting couples picnicked on the water on Sunday afternoons. Upriver, boys canoed out every time a steamship glided past, hoping a few of those passengers in white linen and straw hats would laugh at their antics and

toss coins.

The river was not, in those years, a sullen and muddy conveyor belt for barges. There were circus boats stuffed with clowns and poodles; theater boats wailing over villainy; opera boats that sent heralds ashore to trumpet their performances. Minstrels did the Cakewalk and the Buzzard Lope and the Buck and Wing, told tall tales, sang spirituals, shook tambourines, mocked current events. All the persuaders were on the river: preachers and card-readers, lecturers on mesmerism and the significance of bumps on the skull.

A boat’s trial run was always a holiday—on the John H. Dickey ’s first outing, February 11, 1858, champagne corks popped and guests raised an earnest toast to the captain: “May he pass down the river of life without drifting on the rocks of destruction or the sandbars of deceit.”

On Independence Day 1870, steamers ran excursions down the river, and onlookers watched the Robert E. Lee churn the water, sending up four-foot waves as she raced ahead of the Natchez to win the great race from New Orleans. The guns at Jefferson Barracks fired a salute, and she returned it as she steamed by.

Eight years later, the Veiled Prophet sailed up as though on the River Styx; he would arrive in this fashion every year for decades, standing masked on the hurricane roof of a boat draped in purple and gold, as all the boats along the levee blew their whistles in deference.

On September 9, 1886, a crowd gathered to watch President Andrew Johnson step onto the deck of the Andy Johnson . He was welcomed by three steamers lashed together and many more fanning out behind them to represent the 38 states then in the Union. In October 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt stood waving on the deck of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Mississippi steamer, and the steamboat parade in his honor gathered more and more boats as it made its way downriver.

Even when the river rose, there were grand excursions to see the flooded bottomlands of Illinois from the upper decks of these cake-tiered ships.

And then they began to die off. The Charles P. Chouteau , the first electrically lit steamboat St. Louisans ever saw, burned on the river in 1887. Over the next century, the river’s amusements faded. The grandest boats were anchored, gambled on, scrapped. Soon the

brightest hope would be a gondola.

P.O. BOX 191606 St. Louis, MO 63119 314-918-3000

Company Info

Publications.

- St. Louis Magazine

- Newsletters

- Custom Publishing

- Digital subscriptions

- Manage my account

- Purchase back issues

Copyright 2024 SLM Media Group. All rights reserved.

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, river of history - chapter 4.

Last updated: November 22, 2019

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

111 E. Kellogg Blvd., Suite 105 Saint Paul, MN 55101

651-293-0200 This is the general phone line at the Mississippi River Visitor Center.

Stay Connected

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Steam-powered vessels were important to the growth of the U.S. economy in the antebellum years.

Earth Science, Geography, Physical Geography, Social Studies, World History

Steamboat River Transport

Steamboats proved a popular method of commercial and passenger transportation along the Mississippi River and other inland U.S. rivers in the 19th century. Their relative speed and ability to travel against the current reduced time and expense.

Image from Picturenow

Any seagoing vessel drawing energy from a steam-powered engine can be called a steamboat. However, the term most commonly describes the kind of craft propelled by the turning of steam-driven paddle wheels and often found on rivers in the United States in the 19th century. These boats made use of the steam engine invented by the Englishman Thomas Newcomen in the early 18th century and later improved by James Watt of Scotland. Several Americans made efforts to apply this technology to maritime travel. The United States was expanding inland from the Atlantic coast at the time. There was a need for more efficient river transportation, since it took a great deal of muscle power to move a craft against the current. In 1787, John Fitch demonstrated a working model of the steamboat concept on the Delaware River. The first truly successful design appeared two decades later. It was built by Robert Fulton with the assistance of Robert R. Livingston, the former U.S. minister to France. Fulton’s craft made its first voyage in August of 1807, sailing up the Hudson River from New York City to Albany, New York, at an impressive speed of eight kilometers (five miles) per hour. Fulton then began making this round trip on a regular basis for paying customers. Following this introduction, steamboat traffic grew steadily on the Mississippi River and other river systems in the inland United States. There were numerous kinds of steamboats, which had different functions. The most common type on southern rivers was the packet boat. Packet boats carried human passengers as well as commercial cargo, such as bales of cotton from southern plantations. Compared to other types of craft used at the time, such as flatboats , keelboats , and barges , steamboats greatly reduced both the time and expense of shipping goods to distant markets. For this reason, they were enormously important in the growth and consolidation of the U.S. economy before the Civil War. Steamboats were a fairly dangerous form of transportation, due to their construction and the nature of how they worked. The boilers used to create steam often exploded when they built up too much pressure. Sometimes debris and obstacles—logs or boulders—in the river caused the boats to sink. This meant that steamboats had a short life span of just four to five years on average, making them less cost-effective than other forms of transportation. In the later years of the 19th century, larger steam-powered ships were commonly used to cross the Atlantic Ocean. The Great Western , one of the earliest oceangoing steam-powered ships, was large enough to accommodate more than 200 passengers. Steamships became the predominant vehicles for transatlantic cargo shipping as well as passenger travel. Millions of Europeans immigrated to the United States aboard steamships. By 1900, railroads had long since surpassed steamboats as the dominant form of commercial transport in the United States. Most steamboats were eventually retired, except for a few elegant “showboats” that today serve as tourist attractions.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Mississippi

Why Historic Mississippi Riverboats Continue To Be A Beloved Pastime In The South

Bon voyage!

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Kaitlyn-Yarborough-2000-b9ba0c5b291d49b08647594678365883.jpg)

The Mississippi River has long been a character all its own in the South, brought to life by the words of Southern writers and musicians, as well as through those who have traveled it. The river runs over 2,300 miles and spans 10 states, with a popular stretch running from Memphis to New Orleans. During the early 1800s, steamboats began running up and down the mighty Mississippi, offering a new kind of access to all the towns and ports in between.

The History of Riverboat Cruises on the Mississippi

What started as a shipping venture became a pastime for people to explore the South. The river offered a peek into the culture of the places it flows through. You could explore the roots of jazz, blues, and country, as well as the small towns of the pre- and post-Civil War eras. The many ports-of-call offer the ability to tour and experience a sliver of the South, each with a different view into the area's history. For good or bad, the Mississippi knows the South better than anything else, and the riverboat has always acted as a translator.

Following the first legendary steamboats, such as the Natchez , the industry boomed with thousands of riverboat cruises. Now, you won't find near as many boats floating the Mississippi River, looking like tiered white wedding cakes adorned with red trim.

What Cruise Experiences Are Still Offered Today

The use of the steamboat, which can only run at a speed of around 15 miles-per-hour, has given way for more modern and efficient boat travel. However, there are still day cruises, casino cruises, and even multi-day experience cruises that pay homage to the historic custom.

The tradition continues to survive in the South with a timely point-of-view. American Queen Voyages recently marked its 10th season on the Mississippi River with new experiences (such as events with chef and biscuit queen, Regina Charboneau) on its flagship paddlewheeler, American Queen . Its Lower Mississippi River itineraries have included nine-day journeys that sail between Memphis and New Orleans, with ports-of-call in Vicksburg , Natchez, St. Francisville, Baton Rouge, and more. Additional riverboat options that remain on the Mississippi River include American Cruise Lines and Viking River Cruises , amongst others.

While the historic view of the river might appear differently than a hundred years ago, a ride on a Mississippi riverboat still feels like a step back in time.

Related Articles

Appalachian History

Stories, quotes and anecdotes from Appalachia. 1880s-1950s era.

Snags, Sawyers, and a river on a Boom

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Photo above: Modern day topographic map; arrow points to intersection of Georges Creek and the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy, approximate location of the Favorite’s sinking.

“The steamboat splashing up and down the Sandy River ushered in a colorful, romantic period in the history of the Big Sandy Valley,” begins Carol Crowe-Carraco in The Big Sandy.

“From the third decade of the nineteenth century to the eve of World War I, the clear call of the steamboat whistle, the melodious notes of the calliope, the curses of deckhands, and the halloos of packet travelers joined the chorus of voices of the river.”

But of course there were pitfalls as well.

Some of the dangers found along the Big Sandy can be found along the Ohio River into which it empties; some are specific to it. The Native American Siouan tribe Tutelos, early occupants of the Big Sandy watershed, called the river Tatteroa, which roughly translates as “river of sandbars.” A shallow draft was crucial for steamboats that plied the Big Sandy and its several forks. Then there’s the problem of snags. Rapids and rocks at least could be seen in advance, but a snag was the most significant threat to navigation because it was often undetectable.

River pilots described three kinds of snags. There were “rafts,” or “wooden islands,” composed of an accumulation of logs and tree debris that became grounded on a sandbar or other outcropping from the shore. “Planters” were whole trees that had fallen into the river and become embedded on the bottom, over time becoming reinforced by the build up of silt.

Similar to planters were “sawyers,” groups of trees embedded in the river bottom at a less than perpendicular angle and subject to the pressure of the current, appearing and disappearing at intervals mimicking the motion of a saw at a saw mill. Often groups of planters would have only a foot or two showing above the water. Contrary to their flimsy appearance, planters could quickly ground a boat and tear into its hull.

Trees were constantly falling into the rivers as the banks eroded. And a river on a ‘boom’ compounded that danger. Stretches of mild weather after heavy winter snows or freezes caused not only high waters and flooding, but the loosened ice floes in those fast moving waters acted like sandpaper, scraping away shore trees, piers, and anything anchored to them.

Then there’s the pressure on every riverboat captain to keep to schedule. The slowdowns brought on by the kinds of obstacles mentioned above made the situation worse.

“I have seen these boats coming down the river like they were shot out of a cannon, turning these short bends , missing great limbs hanging over the stream from huge trees, and finally shooting out of the Big Sandy into the Ohio so fast that often they would be nearly a mile below the wharf boat before they could be stopped,” says Captain Ellis C. Mace in ‘ River Steamboats and Steamboat Men, a History.’

“In 1878, the federal government undertook the improvement of the Big Sandy River,” says Crowe-Carraco. “As funds became available, the Corps of Engineers cleared channel obstructions, removed rocks from 56 bends, and cut overhanging trees. Ugly government snagboats, commonly called ‘Uncle Sam’s toothpullers,’ removed snags and sawyers. While these improvements benefited navigation to a certain extent, they were only temporary measures and did not provide satisfactory depths for continuous navigation.”

And that brings us to the year 1879 and the tale of the Favorite , the grand old lady of the Sandy, a steamboat that had plied its waters for 30 years. The Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy was navigable by steamboats from Pikeville, where this story begins:

“Thirty-five years ago, 1879 arrived during a warm spell of weather that just about equaled this winter,” writes Edith Walters in her mother’s voice, in a term paper for the University of Pikeville. “On new years’ day peach trees were blooming. I had finished teaching my five months school and decided to visit my aunt and cousins in Lawrence County.

“I left Pikeville in the afternoon of January 21st on a steamboat, the only way of winter travel in those days. When I arrived at Buchanan at two a.m. the weather had become very cold and it was snowing. This continued for several days. The Big Sandy froze over and boats could not run. In the latter part of February the rain came, snow melted, the ice broke and Big Sandy went on a ‘boom’ as the river men called it.

“I had a letter from home saying – ‘come home at once. Mother is sick.‘ We called Catlettsburg and made arrangements for a boat to stop. Just after dark a steamboat whistled for that landing and we hastened to the river. When it landed we learned it was the Favorite , one of the oldest and smallest boats on the river [ed.-28 feet wide and 147 feet long]. Being in a hurry to get home, we get on board—Mrs. Burris Wright, and her brother from Praise, and myself.

“There was no ‘ladies cabin’ on this boat so they took us to the Pilot house where we had to sit up all night. A little after midnight we met a steamboat coming from Pikeville and the captain-Rhodes Owens-called to our pilot and told him he had better ‘tie up below Georges Creek and wait for day light—there were some trees lodged in the river and ‘twas dangerous.’

“Well, he didn’t tie up, and between four and five a. m. I felt a distinct jolt and shudder. I said ‘Aren’t we on that tree now?’ The pilot didn’t answer, the boat began tilting sideways, and I asked if we were turning over. The pilot said ‘yes.’

“Rose and I both started for the window but he told us to wait a minute and he got out first. We made a second jump and Rose got out first with me not far behind. We were standing by the pilot house saying,

“Where will we go?”

”What will we do?”

“We could hear the water running into the fire and the steam was awful. The men were as frightened as we were. Seconds seemed minutes. The old captain was sleeping in a little room behind the Pilot House and he ran out and yelled, ‘Come this way.’ We came toward him. Rose happened to be nearest him and she was little; he caught her up and ran along the top of the boat till he could lift her to another man who had already gotten out on the tree top. There must have been two or three trees piled in there together.

“When we got to the edge of the boat with Rose I was just behind him. I had seen Dr. Gray as we went through the boat the night before so I said, ‘Oh, Dr. Gray, where are you?’ He answered from the tree top and happened to be the man who was holding Rose on the tree.

“Captain [Payton S.] Davidson stood on that old leg and I sat on the edge of the boat roof and he helped me off.

“The men who were in the main cabin and engine room climbed stairs for their lives, the boat sinking so quickly many of them were knee deep in water.

“The Favorite had struck the body of one of those trees like a wagon on a bank. Being old and rotten it broke in the middle and down it went.

“Daylight found it with the Pilot House and rear end of the boat standing above the water and only the man slightly injured. My trunk was found three miles below the place where the Favorite sank.

“The passengers and crew, about thirty or forty souls, were scattered over those treetops like chickens. After daylight men who lived on the river bank brought a skiff and took us ashore.

“The farmers kept us and fed us until the next morning when another larger boat came along, and we got home without more trouble. I have heard many different tales about our rescue and how men swam out with us but we women never had our feet wet. The only persons who swam out were two boys who became so frightened they jumped into the raging, ice cold waters and swam ashore, which seemed almost impossible. No one was drowned and only one man slightly injured.”

By 1944, when Mace wrote his riverboat history, disasters like that befalling the Favorite were a distant memory. “Riches have crowned the Sandy Valley,” he said. “Great cities have sprung up on the Tug and Levisa forks. The railroad runs on both sides, and the great activity that these old-time steam boats caused has all disappeared. Outside of certain sections, all is quiet. Railroads do not create the general excitement and hustle among the people that the steamboat did, on account of the short season that the packets could run. The railroad crowded them entirely out, and now many of the younger set have never seen a steamboat on the Big Sandy.”

sources: Kentucky River Development: The Commonwealth’s Waterway , by Leland R. Johnson & Charles E. Parrish, 1999, US Army Corps of Engineers, Louisville District

“The Sinking of the Favorite,” by Edith Walters, “Folk Tales of the Cumberlan’s,” University of Pikeville Archives

Steam Navigation on the Levisa Fork, by Russell Lee Whitlock; Rootsweb site

More articles on river boats:

The ice knocked ‘The Greenland’ off the cradles and down the river(Opens in a new browser tab)

Last of the packet boats(Opens in a new browser tab)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

The Mississippi River

Mississippi River History

St. Paul and Minneapolis exist today because of riverboats. In fact, virtually every city along the major rivers of the United States can trace its very existence to the arrival of riverboats in America. In the early 1800s, the Minnesota Territory was inhabited by Native Americans, soldiers, trappers, traders, explorers, and lumbermen. The cities, if you could call them that, were little more than camps where these rugged individuals congregated to drink, play cards, fight, and rest.

Native Americans hunted and farmed in the Mississippi valley for hundreds of years before white men arrived. The first European settlement in the Twin Cities area was Fort Snelling. In 1805, President Thomas Jefferson sent a young army Lieutenant, Zebulon Pike, into the area to find a suitable site to build a military outpost. Two years earlier, President Jefferson had purchased the entire central portion of the country from the Canadian border to the Gulf of Mexico from Napoleon Bonaparte of France. That land agreement was called the Louisiana Purchase. President Jefferson wanted an army post in Minnesota to protect the country’s new land from the British and to keep the peace between warring Indian nations—the Dakota and Ojibway.

Lt. Zebulon Pike

Arriving at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers in the summer of 1805, Lt. Pike met French-Canadian Fur Trader Jean Baptiste Faribault repairing his canoe at the lower end of the island. After exploring the area, Pike determined that the bluffs overlooking the island between the two rivers would be an excellent location for the fort. That island eventually was named Pike Island, in his honor.

Col. Josiah Snelling

Fourteen years later, the first contingent of soldiers, led by Col. Henry Leavenworth, arrived to begin construction of the fort, originally called Fort St. Anthony. They endured extreme hardships in the first year, and nearly 40 men died over the winter. A new commander, Col. Josiah Snelling, took charge in 1820 and over the next four years, he supervised construction. Upon completion of the new military complex, Gen. Winfield Scott came from Washington D.C. to inspect the fort. He was so impressed with what Snelling and his men had accomplished in the wilderness that he recommended to Congress that they rename the facility Fort Snelling.

A Place Called Pig’s Eye

In the 1830s, a rugged frontiersman came to the Minnesota Territory. Known as Pig’s Eye Parrant because of a battered face he had acquired as a result of too many barroom brawls, the bawdy newcomer discovered a cave on the north bank of the Mississippi River about four miles downriver from Fort Snelling. In the cave was a marvelous, spring-fed stream; thus, given the name Fountain Cave. Ole Pig’s Eye, who brewed liquor, decided that Fountain Cave was a perfect place for his home and business. He quickly found many customers at Fort Snelling.

Over the years, a number of civilians had migrated down from Canada and settled on the government land surrounding Fort Snelling. By 1838, the new commandant became concerned with the growing civilian population at the Fort. He told them to leave Fort property, and when they refused, he ordered his troops into their settlement. The soldiers forced the civilians out of the area and burned their homes. There was no other white settlement for hundreds of miles, so 150 families wandered down the river until they came to Pig’s Eye Cave. Fresh water, unlimited hunting and fishing, and a ready supply of lumber made the cave a perfect place to live. The people formed a new community, and they called it Pig’s Eye.

Three years later, in 1841, a Catholic priest named Father Lucien Galtier arrived and built a small log chapel about a mile downstream (near the present site of the Robert Street Bridge). Every Sunday, the people of the Pig’s Eye community traveled down river to Father Galtier’s chapel. Soon, they became dissatisfied with the name of the community and decided to change it to the name of that little chapel. It was the Chapel of Saint Paul. That is how the city of St. Paul began at Fountain Cave, which was located approximately where the ADM Grain Terminal is today along Shepherd Road, just upriver from the downtown area.

Riverboats Create St. Paul

Over the next few years, the tiny community grew slowly until the big riverboats suddenly began to venture north on the Mississippi River. Please remember, there were no cars, trucks, trains, or airplanes. Travel was done through the woods by walking, riding a horse, in a wagon pulled by horse/oxen, or by boat. Rivers were the “freeways” of the 1800s. Travel was faster and much more comfortable on the big riverboats than by any other means. By the 1850s, hundreds of riverboats were coming to St. Paul bringing all types of goods and thousands of people. The entire Minnesota Territory had a non-Indian population of about 6,000 people in 1850. By the early 1860s, the population had exploded to 200,000. Almost all of those new residents arrived by riverboat.

Riverboat traffic began modestly in 1847 with 47 vessels arriving in Saint Paul—including the riverboat Lynx with a 23-year-old school teacher named Harriet Bishop. Riverboat arrivals increased each year, attaining peaks of 1,027 in 1857 and 1,068 in 1858 (the year Minnesota became a state). Severe national economic depression struck in 1859, slashing riverboat arrivals to 808. Arrivals held relatively steady into the 1860s, when the Civil War dominated national attention. During the war, many riverboats transported military troops and supplies throughout the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Some were even converted to early battleships using bales of cotton stacked high around their perimeters to defend against hostile gunfire. As the war ended, steel rails were being laid across the country, and riverboat landings in St. Paul plummeted almost to extinction.

You can see that riverboats truly did play a vital role in the creation of St. Paul. However, as marvelous as these big boats were, they posed many serious threats. In those early days, riverboats were powered by giant steam engines. Steam engines used wood that was in abundant supply along the river shores for fuel. Unfortunately, steam engines were under tremendous pressure, and the boilers frequently exploded, destroying the riverboat and killing many passengers and crew. Another danger was fire that could be started by hot sparks, which billowed out of the riverboat’s smokestacks. If the riverboat somehow managed to avoid fire and explosion, they also faced peril from rocks and snags (dead trees) under the water that could puncture the wooden hull and sink the boat.

Traveling the river was a very dangerous experience but one that many people made in the hope of reaching this new land of lush woods and abundant wildlife. Just to prove that human beings are not totally without hope, we did learn from those early mistakes. Today, riverboat travel is extremely safe due to the upgrades that have been made in vessel construction, course plotting, river maintenance, and crew training.

* All historic paintings are from the private collection of Capt. William D. Bowell, Sr., founder of the Padelford Packet Boat Co., Inc. The paintings were done by Padelford employee Ken Fox.

Gift Certificates, Season Passes & Promotions

Gift Certificates

Buy Online, Redeem Online

Special Offers

Family Season Passes

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Padelford Riverboats 205 DR Justus Ohage Blvd. Harriet Island St. Paul, MN 55107

LOCAL: 651-227-1100

- S&D Reflector

- J. Mack Gamble Fund

- Subscriptions

- Annual Meeting

Who We Are

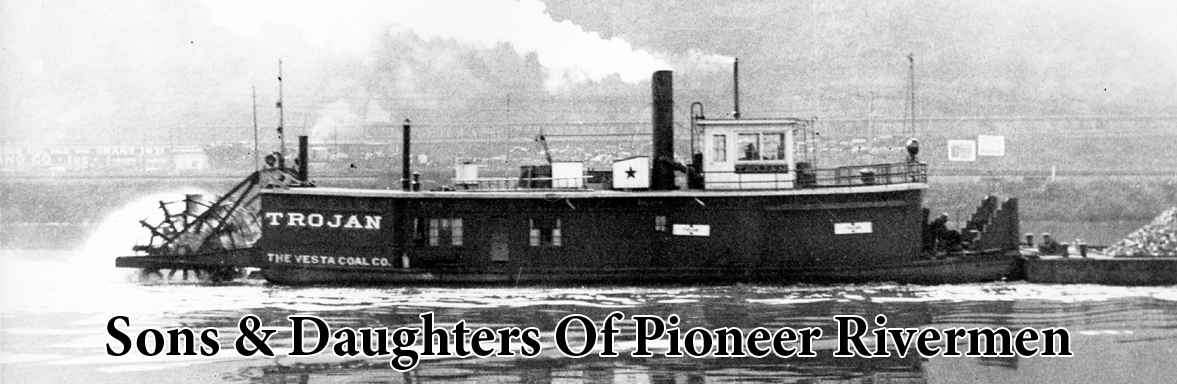

The Sons and Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen (S&D) was established in 1939 to perpetuate the memory of Pioneer Rivermen and for the preservation of river history.

Join the former and active riverboat captains, crew and their families, historians, artists, model builders and those with an interest in the history of the people and boats of the Mississippi River system in sustaining a uniquely American tradition. Subscription is not restricted to descendants of river pioneers, the only requirement for a subscription is in interest in river history!

83rd Annual Meeting - September 15th & 16th, 2023

History In Your Own Backyard Video Showcasing S&D

Adjunct Organizations

- Ohio River Museum

- Inland Rivers Library

- Blennerhassett Museum

Other River Museums

- Ohio Valley River Museum - Clarington, OH

- Point Pleasant River Museum & Learning Center - Point Pleasant, WV

- Old Lock 34 Visitor Center & Museum - Chilo, OH

- Howard Steamboat Museum - Jeffersonville, IN

Sail Aboard a Floating Masterpiece to Discover a New Side of America’s History

For those yearning for something deeper, a voyage down America’s waterways on an authentic paddlewheel riverboat offers a rich discovery of the continent

Since time immemorial, rivers have represented a fundamental exchange—their flow and direction providing the essential ingredients throughout history for burgeoning cities and towns, transportation, trade—even life itself. With that, it’s no surprise that cruising along gentle waters transports us to a place of stillness and peace, sparking a curiosity for the people who traveled these waters before us.

And, aboard a classic American riverboat, like those of American Queen Voyages, a deeper connection with the North American continent, its history, people, and legacy are never far. The flagship vessel, American Queen , is a gentle soul packaged with ornate detailing, inviting visitors to revel in new adventures onboard through its world-class dining, relaxation, enrichment and onshore excursions. With history all around, a dedicated interpreter provides context onboard. And, with vessels ranging from iconic paddlewheelers to state-of-the-art ships, no two trips are quite alike.

To see some of America’s natural beauty and history come to life, read on to discover it for yourself.

Steamboat History

One-hundred-and-fifty-years ago, before the adoption of widespread train travel, rivers were America’s main source of trade, providing necessary resources to rapidly expanding ports and their growing developments. Even earlier still, Native American peoples had utilized these rivers for thousands of years—including the Mississippi, which later became one of the country’s most essential waterways.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/08/33087c41-cac5-4f49-a58a-3b0f38bde5cb/americanqueenvoyages-19962018_pgjvcp-1_1-v1.png)

Today, the lower Mississippi offers a glimpse into an American past that’s often overlooked. Small towns brimming with history welcome visitors to their shores, while massive barges transporting grain and cotton bypass tugboats assisting ocean-going vessels up the waters of this incredible marine highway. Along its banks, bald cypress and Spanish moss draped trees stand watch, and deer and muskrats make their homes. The river’s slow, lapping waters carry a sense of tranquility, calling to mind a simpler time where river cruising was America’s main form of travel—and an elegant one at that.

American Queen History

American Queen Voyages’ fleet of classic American riverboats offer passengers an opportunity to experience a unique chapter of history—whether it’s along the Mississippi or gliding upon the bucolic rivers of the Pacific Northwest—forging a deeper connection to the continent itself, as well as its history and heritage in the process. American Queen is the company’s flagship vessel, a masterful recreation of a Victorian-era steamboat. The 418-foot-long vessel—believed to be the largest steamboat ever built—boasts 213 staterooms, six passenger decks, and a wealth of gingerbread fretwork. It even has a genuine steam engine. “The engine was pulled out of the U.S. dredge Kennedy,” says Frank Rivera, the Queen’s riverlorian (a term that means part-historian, part purveyor of river lore). “She literally is the queen of the river.”

The steamboat revolutionized trade upon waterways. In 1803, American inventor Robert Fulton showcased his first steamboat prototype in Paris, where he caught the attention of American Ambassador to France, Robert Livingstone. The two formed a partnership, and after returning to the States, created the New Orleans , a small demo boat designed with innovative steam-powered propulsion, which allowed commerce to travel upstream, as well as down, for the first time ever.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/db/15db9103-9262-4746-bc99-053d47dd8eb5/americanqueenvoyages-sailing_day_lock_boat_ext_282_of_1529_1-v1.png)

In 1811, the New Orleans made its inaugural journey from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. Although its billowing smoke and the roar of the boat’s engine originally instilled fear in those along the riverbanks, by the time the New Orleans reached its namesake city, it was met with a hero’s welcome. People cheered as—rather than dismantling the ship at the voyage’s southern terminus and selling its parts for wood as was the norm at the time—the New Orleans simply reloaded and returned upriver. The feat was unprecedented. And in the decades since, modern ingenuity, such as quieter propulsion and the use of low-sulfur fuels, has resulted in such riverboats becoming a comfortable and luxurious way to see the country. These types of technological advancements are a trait that’s shared among all American Queen Voyages vessels, each with their own unique histories and stories to tell.

American Queen brought this kind of relaxing, slow-moving sojourn (“The average speed of our riverboat is three to five miles an hour,” says Rivera) back to life. When godmother Priscilla Presley christened the vessel in Memphis back in 2012, American river cruising was reborn.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0e/b6/0eb6c081-4e66-44c1-a9fc-7369f41c555d/americanqueen-aqsc_aq_grand_staircase_00138_1-v1.png)

Today, passengers can catch world-class entertainment in American Queen’s Grand Saloon, an exact replica of the Ford Theatre in Washington D.C.; browse a library of books in the Mark Twain Gallery, which boasts one of the country’s largest collections of Tiffany lamps; and enjoy a five-course dinner at the J.M. White Dining Room, a duplicate of the dining space on the palatial J.M. White, one of the most sumptuous river steamers ever built. Among the Queen’s most impressive historic features is her steam calliope: a glistening steam whistle organ with 37 gold-plated whistles that sing out in salute once the riverboat’s large red paddlewheel starts churning.

“It’s a throwback to a bygone era,” says Rivera, “Of course, the boat now includes excursions to riverside cities and towns as well.”

Onboard American Queen , guests can engage with a Mark Twain interpreter who brings history to life in the author and humorist himself, learn from naturalists and historians as they celebrate the river's many eras and landscapes, and hear talks given by Rivera himself, whose knowledge of river history and lore—from the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 to the stories behind old riverboat terms like “high-falootin” and “blowing your stack”—abounds.

The Queen’s sister vessels are equally as impressive. There’s the fleet’s newest jewel, American Countess , a sleek and bold contemporary paddlewheeler christened for sailing in 2020, and American Empress , the largest overnight riverboat west of the Mississippi. Passengers can delight in vast collections of intricate artifacts from Alaska Natives, Russia, the Gold Rush and the sternwheeler era; as well as culinary offerings inspired by the natural bounty of America’s Pacific Northwest.

“When you're traveling along the river you're still passing all these places that you wouldn't see otherwise,” says Rivera. “Riverboats give passengers the opportunity to get out and explore.”

American Queen Destinations

Over the course of its 9-day journey from Memphis to New Orleans (or reverse), American Queen makes stops at the lower Mississippi’s most charming ports-of-call.

Passengers boarding in Memphis are treated to a city steeped in history, from music—which includes the Memphis blues sound, the Blues Music Hall of Fame, and Elvis’ Graceland estate—to Civil Rights. In fact, its National Civil Rights Museum is built around the Lorraine Motel, the site of Martin Luther King Jr. 's 1968 assassination. For a deeper dive into Memphis as a whole, a visit to the city’s Beale Street Historic District is a must.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/a4/b1a4fd3f-3c7e-4b5c-9be9-286ce6ddac05/americanqueenvoyages-nationalcivilrightsmuseum-v1.png)

Disembarking in New Orleans, passengers can savor this spirited center of jazz, cultural fusion, and gourmet cuisine (think succulent seafood jambalaya and crawfish etouffee) at a pace all their own.

From exploring charming river towns where history comes alive to deeply discovering destinations through insightful enrichment, entertainment and regionally inspired cuisines, experience a truly transformative trip along America’s historic waterways with American Queen Voyages.

Where would you like to go? Find A Voyage

The Editorial Staff of Smithsonian magazine had no role in this content's preparation.

Historic Riverboats

Although Iowa is a landlocked state, it still has a long history of relying on rivers and river boats for travel and trade. The first Indigenous people came to Iowa by following the river valleys, and heavily depended on the rivers for many things, such as providing fresh water for cooking, drinking and gathering edible plants. Many years later, after the creation of the steam engine, Iowa's settlement pattern reflected the steam-power revolution. Along Iowa's major rivers, towns boomed and prospered. They became trade centers where goods could be sold and sent downriver to market. Today, while Iowa's rivers are not used for transporting goods and people at the volume they once were, they are still important to the state's economy.

Explore the activities, videos and additional resources in this at-home expedition to discover more about the importance of rivers throughout Iowa's history. Also, learn about four featured National Historic Landmarks in Iowa that have deep ties to this expedition theme.

- Brief Summary of the History of River Transportation in Iowa

- Featured National Historic Landmarks

Set Sail with Innovative Iowans

Iowa has a long history of relying on rivers for travel and trade. In this Innovative Iowans activity , young historians will learn about the four riverboats in Iowa that are National Historic Landmarks, design and create origami paper boats and test their seaworthiness.

Solve the Word Search

Find the listed words hidden in the grid of letters in this Goldie's word search puzzle . The words in this puzzle are inspired by historic riverboats and river transportation in Iowa.

Explore National Historic Landmarks

Learn more about the four seaworthy National Historic Landmarks in Iowa showcased in this at-home expedition. + Video: William M. Black Dredge Boat: The Dustpan + Website: William M. Black Dredge Boat + Video: Lone Star Steamer + Website: Lone Star Steamer at Buffalo Bill Museum + Video: Aerial View of George M. Verity Riverboat + Website: George M. Verity River Museum + Website: Sergeant Floyd Towboat

Watch Videos

View additional videos about the National Historic Landmarks and the history of river transportation in Iowa from the National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium and Iowa PBS. + "William M. Black: Engine Room Communication" + William M. Black Dredge Boat Historical Footage from 1952 + "Steamboats" from Iowa PBS + "Steamboats on the Red River" from Iowa PBS

Research with Primary Sources

Analyze primary source sets to view photographs, maps and more cataloging the history of river transportation and innovation in Iowa. + Transportation in Rural and Urban Spaces + Environmental Impact + Innovation in Transportation

Discover Additional Resources

Check out kid-friendly videos, articles and other resources about Iowa's history of riverboats and river transportation. + The Goldfinch: Rivers in Iowa + The Palimpsest - "In the Steamboat Era" + Video: "Steamboat Accidents" from Iowa PBS + Video: "Mississippi River Fuels Iowa Industry" from Iowa PBS + Transcribed records, newspaper clippings, historical accounts and diary entries about life on the Missouri River

- State Historical Society

- Iowa Humanities Council

- Mission & Strategic Plan

- Boards & Commissions

- Sponsorship Levels

- Gala Logistics & Accessibility

- Weddings & Receptions

- Facility Rental Details

- Employment & Internships

- Renovations

- Iowa's 175 Anniversary

- Iowa National Statuary Hall

- Other Funding Opportunities

- Field Assistance

- History Education

- Lifelong Learning

- Emergency Resources

- Local History Network

- Travel Iowa

History of Riverboat Gambling on the Mississippi

The South has always been at least somewhat friendly to gambling due to the rise of the riverboat in the early 1900s. Games of chance were kept on the water so that anti-gambling laws wouldn’t apply. Games like poker and roulette took place on grand riverboats, even if the ship never left the dock.

This tradition was greatly reduced when the railroad became the main way to transport both goods and people, but some riverboats remain in the South today. In Mississippi and Louisiana, especially, retired steamboats are now used for river cruising and for gambling in places like Vicksburg.

Online casinos are one of the latest innovations in the casino industry. Since the rise of technological advancements, they are solid competitors to U.S.-based land-based casinos. Many gambling restrictions still remain in the South and across the ocean. For example, every casino in the UK gets licensed by the UK Gambling Commission.

The regulations of the U.S. online casino market have led to developers existing who only get associated with U.S. casinos and are not available at UK-based gaming sites. Some famous developers for the U.S. market are RealTime Gaming, Relax Gaming, Rival Gaming, Elk Studios and Betsoft.

But for those players who want the old-time experience of dressing up and boarding a grand steamboat, the South has plenty for them. Just look along the Mississippi River from Missouri to Louisiana. According to Visit Mississippi , the first steamboat to travel the Mississippi River was the New Orleans, whose October 1811 maiden voyage began in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The New Orleans stopped in Natchez in December 1811 before continuing to its final port in New Orleans.

Wealthy Southerners could afford to travel by steamboat, and some were ornately decorated in the Victorian style. The riverboat casinos that remain today continue that grand tradition, with music playing onboard, restaurants available to players and even live entertainment offered regularly.

So, if you want to step back in time and experience the old South by river—without all the outlaws and pirates —consider a riverboat cruise or evening of gaming.

SHARE THIS STORY:

Eco-conscious travel, the wild history of, related articles.

3 Must-Visit Histori

6 Creative Trips Thr

Best Photo Spots in

No comments, leave a comment cancel reply.

Grand Rapids in 1856

Scene of early Grand Rapids viewed from the...

History Grand Rapids by the Grand Rapids Historical Commission

- Publications

- Primary Sources

- Interpreting Historical Images

- Citation Guide

- Related Websites

- Architecture

- Before and After

- Photo Essay

- Collections

GRHC - September 23rd, 2009

Grand Rapids Historical Commission and the Community Media Center present "Glance at the Past", a local history radio project. This week's episode tells of twin riverboats that cruised the Grand River at the turn of the century.

The Grand and the Rapids, were two classic steamboats built in 1905 by the Grand Rapids-Lake Michigan Transportation Co., formed by several prominent local businessmen. These gentlemen thought they could compete profitably with the Interurban rail system by transporting people and goods from “the rapids” to “the haven on the Grand” or Grand Haven as we know it today.

The hulls were built at the boatyard located on the west bank of the Grand River just north of Wealthy St. As soon as the shell was complete it went into the water and the steamer was finished as it floated on the river. The wooden ships were identical in size, 134 ft long by 28 ft wide.

The machinery to operate the boats was built by the Clinton Novelty Iron Works of Clinton, Iowa, a city on the Mississippi known for riverboat building. All of the machinery and iron-work for the boats was built there and shipped to Grand Rapids. When completed each ship was registered at Grand Haven.

But alas, these riverboats could not compete with faster rail service and soon were out of business. By 1908 both were in Marquette, and a year later they were on the Mississippi at Memphis. The twin sternwheelers came to unhappy ends; the Grand burned in 1921 in Lousiana and the Rapids was crushed by ice and sank in the Ohio River in 1917.

Full Details

">Add to Your Site

Copy and paste the code into the HTML of your site.

- Grand River

Riverboat Casinos in the US – History of Riverboat Casino Gambling

Author: Muhammad Gregory

History of Gambling on Riverboats

We can think of no better place to begin our journey than by painting a picture of the history and heritage of riverboats and gambling . Back in the 1800s, the situation for gambling in the USA was a bit different than today. The Mississippi Great River was the lifeblood of American industry and commerce. Thanks to advances in transportation technology, traders were no longer content to load up their horses and carts and instead took full advantage of the connections that river transport could offer.

If you’ve ever read anything about sailors, you’ll know that traveling over water can be a long and tedious endeavor, which is why boats and game of chance have a long illustrious history . In order to pass the time, passengers and merchants on these riverboats would gamble onboard to keep themselves entertained on long voyages.

The Big Muddy

Before you knew it, riverboats began to entice professional gamblers and those seeking to keep a low profile. This was in part due to states prohibiting gambling ashore, making the use of riverboats a clever means of sidestepping local gambling laws as the water freeways were largely unregulated.

As the Mississippi River bordered several different states, it was the perfect legal grey area . This led to riverboats becoming popular entertainment destinations that mixed live music, dancing, and gambling, if only for a few hours. However, the rise of the railroad and the American Civil War in the latter half of the 19th century saw the popularity of water transport and riverboat casinos decline significantly.

It wasn’t until 1904 when several states softened their hardline stance on riverside gambling. The first ‘legitimate’ riverboat casino, the City of Traverse, set sail on Lake Michigan which signaled the start of riverboat gambling becoming an organized commercial operation. As you may know, whenever there’s money to be made, it isn’t long until the government wants to get involved.

The Road to Regulation

Early riverboat casinos were quite restrictive in terms of what they were legally allowed to do. Gambling could only take place during a short cruise that lasted several hours. In 1951, Lyndon Johnson drafted the Transportation of Gambling Devices Act, which made the transportation of gambling devices illegal across state lines unless it was legal in the next state.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that the idea of revitalizing this golden era of riverboat gambling re-emerged. As a result, several states introduced laws which allowed gambling on water vessels and set the legal framework with which they still operate in today. Iowa was the first state to legalize riverboat gambling in 1989. Nowadays you can gamble on riverboat in the following states:

- Mississippi

In many ways, it was a win-win situation, states could earn money from riverboat casino revenues through taxation without the pressure of offending the righteous by having the temptations of on-land casinos everywhere.

Riverboat Casinos and Local Economies

By 2010, there were a total of 17 riverboat casinos in operation. By 2018, there were a total of 63 riverboat casinos operating across these six states, suggesting the appeal of maritime gambling is continuing to grow according to this latest data. For the entire states of Illinois and Missouri, these riverboat casinos made $382.5 million and $152.million in state tax revenue alone.

A major way that a riverboat casino collects revenue for the state is through taxation of winnings , although be sure to consult the gambling legislation in the state you’re playing in. For example, in Iowa, if you win more at $1,200 there you must pay over 5% in taxes. Whereas in Illinois, a larger 15% of your winnings return to the state, and a further 5% to the local community.

Vocal supporters of riverboat casinos argue in their favor that they actually increase employment rates in the communities that host them, and this does indeed seem to be the case. Although the impact of the global Corona pandemic on riverboat casinos remains to be seen, we predict that this industry will continue to grow.

Interesting Trivia Surrounding Riverboat Casinos

Before we give you some riverboat recommendations, we’d like to give you some riverboat casino trivia and historical facts that you might find intriguing.

Firstly, when riverboat gambling was legalized in the early 1990s, different states demanded different cosmetic requirements . For instance, all Louisiana vessels were required by law to look exactly like the 19th-century paddlewheel steamboats. In Indiana, riverboat casinos legally had to be 150 feet long and able to accommodate at least 500 passengers.

Riverboat gambling also comes with a history of violence. Modern historians have found sources that report on individuals taking the law into their own hands to punish cheaters and thieves. The most famous incident occurred in Vicksburg, Mississippi when five gamblers were lynched in 1835 after they were discovered to be cheating.

Initially, in most states, players were only allowed to gamble when the riverboat casino was in motion. However, due to unpredictable and terrible weather, boats occasionally couldn’t leave the shore for safety reasons. After Hurricane Katrina, most states require riverboat casinos to stay docked to the barge to prevent damage and accidents.

Riverboat Casinos in the Modern Day

Today the Mississippi river retains its reputation for being the home to many extravagant riverboat casinos. This section will take a look at some our top three picks for the best riverboat casinos out there that we wholeheartedly recommend you visit.

Casino Queen Marquette – Iowa

Situated in the heart of Marquette, Iowa, the Casino Queen Marquette promises visitors an unforgettable experience of ”high rollin’ on the river”. This remarkable riverboat has plenty of floor space, 17,514 square feet to be exact! Gamblers can also enjoy over 566 slot machines and table games such as blackjack and Texas Hold’em. If you’d like to immerse yourself with the locals, you can enjoy a few rounds of Mississippi Stud poker too.

Treasure Chest Casino – Louisiana

Located in the cultural capital of Louisiana, New Orleans, the Treasure Chest Casino offers players a beautiful gaming experience alongside the breathtaking Lake Pontchartrain . It boats 24,000 square feet of floor space hosting classic table games, slots, and an exciting event showroom. Highly recommended for tourists traveling through the American South East, visitors can also experience traditional Southern hospitality and cuisine including Po’boys, crawfish, and gumbo.

Ameristar Casino – Mississippi

Found on banks of the famed Mississippi, the Ameristar Casino can be found in Vicksburg and contains a massive poker room, café, restaurant, and even a highly recommended hotel. It was designed to retain the appearance and atmosphere of the 19th-century traditional steam paddle riverboat. Visitors can enjoy this nostalgic character whilst simultaneously enjoying table games, over 1,400 slot machines, and even sports betting kiosks, meaning there’s something for everyone who visits.

Frequently Asked Questions

If this article has piqued your curiosity enough to set sail on a raft down the Mississippi to find the best riverboat casinos, we’re happy to hear it! However, if you should still have some unanswered questions about riverboat casinos, we’ve got you covered. Featured below are the most commonly asked questions by our readers.

If you’d like to enjoy the full experience of a riverboat casino without having to go near the water, then be sure to check out our extensive range of in-depth gaming guides that will give you all the insight and tips you’ll ever need when it comes to playing all of your favorite games online or at a live casino.

Are there still riverboat casinos?

Of course, modern riverboat casinos have been popular since the early 1990s . Iowa was the first state to legalize riverboat gambling, with several states bordering the Mississippi river like Mississippi, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and Louisiana jumping on the bandwagon shortly after. If riverboats aren’t your thing however, there are plenty of great new online casinos popping up all the time.

Why are there riverboat casinos?

Riverboat casinos arose as a solution to legally grey areas regarding state gambling laws . They were seen as a way for the state to increase its revenue by taxation while also preventing illegal behaviors. Riverboat casinos offered a steady flow of income without citizens worrying about a flurry of on-land casinos popping up in their area. Today they are mostly docked to the harbors and offer entertainment, music, table games, and sports betting options.

How many riverboat casinos are there?

According to the latest figures provided in 2018, there are currently a total 63 riverboat casinos operating across the states of Iowa, Mississippi, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, and Missouri. All of these are packed with entertainment options and many classic casino games such as blackjack and roulette .

How much does a riverboat casino cost?

Riverboat casinos have been reported to cost anywhere between $7 million and $20 million . This is without even taking into consideration the additional cost of installing gambling equipment for its patrons. Typically installed by shipyards, additional gambling equipment such as slot machines can run up further bills of up to $6 million.

Latest Guides

Traditional Poker vs Video Poker

The Casino Lawsuits Landscape

The World’s Biggest Poker Tournaments

By visiting our website, you are declaring that you are 18+ and agree to our Terms and Conditions , Privacy Policy , and to accept our use of Cookies . This website contains advertisement.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘A narrative of triumph’: a powerful 17-acre site in Alabama remembers enslavement

The Freedom Monument Sculpture Park is an expansive new experience that aims to pay an honest tribute to courage and resilience as an American equivalent to a Holocaust memorial

“T he morning after our whipping, we all had to go to work, as if nothing had happened. I was so sore I could hardly do anything,” recalled James Matthews, who, like many enslaved people after a severe whipping, ran away into the woods. “I have known a great many who never came back; they were whipped so bad they never got well, but died in the woods, and their bodies have been found by people hunting. White men come in sometimes with collars and chains and bells, which they had taken from dead slaves. They just take off their irons and then leave them, and think no more about them.”

This quotation from Matthews’s Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave (1838) appears on a panel in the woodland setting of the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park in Montgomery, Alabama, a seamless blend of art and history opening on the banks of the Alabama River on 27 March. It is one of many first-person accounts that serve as a rebuke to historical amnesia, to deletion by indifference, to those who “think no more about them”. The park’s artefacts and sculptures and its climactic monument are a radical act of remembrance rooted in a sense of place.

Whereas commemoration of the Holocaust has a locus in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum and other sites across Europe, tracing the memory of the 10 million Black people enslaved in America can often feel like a succession of absences. Plantations survive but with a built environment that makes it hard to avoid the centrality of the enslaver. Countless graves and cemeteries of the formerly enslaved are buried under interstate highways, shopping malls or car parks. Some African Americans travel to west Africa in search of a tangible connection with ancestors.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a non-profit organisation that already runs the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery , seeks to close this gap with the 17-acre site built for an estimated $12m to $15m. Visitors can arrive by boat on the same waters that once trafficked enslaved people, then step inside 170-year-old dwellings from cotton plantations as well as recreations of holding pens and railway carriages. They will hear trains running on nearby railway tracks built by enslaved hands.

Bryan Stevenson , executive director of the EJI, says in an interview: “We’ve done a poor job in America of reckoning with our history of slavery. There just aren’t places people can go and have an honest encounter with that history that centres on the lives of enslaved people. In Europe, what’s happened in Germany, in Berlin and other cities, has made Holocaust memorials and sites of remembrance such powerful places. When you go to the camps, it’s hard to avoid the power and the weight of that history.

“We’ve avoided confronting the weight of our history in ways that have undermined our ability to achieve the sort of progress and justice that many of us want. I do hope that people will come here and be sobered by the history but also inspired by the people who survived, endured, persevered and went on to commit to building an America that has so much potential.”

The river is the first artefact. Forming just north of Montgomery and flowing 318 miles, it was bordered by plantations and forced labour camps and traversed for decades by boats carrying 200 enslaved people at a time. To be trafficked south by steamship – in overcrowded conditions with little protection from the elements – was to be “sold down the river” .

One enslaved person forced to work on a river boat recalled: “A drove of slaves on a southern steamboat, bound for the cotton or sugar regions, is an occurrence so common, that no one, not even the passengers, appear to notice it, though they clank their chains at every step.”

Once disembarked, visitors follow a path through the sculpture park’s native elm, oak, sycamore, cottonwood and chinaberry trees and survey art in an evocative natural landscape. Eva Oertli and Beat Huber’s 2014 concrete sculpture, The Caring Hand , presents five giant fingers protruding from the earth around a tree as the river flows beyond.

It is one of several pieces – about half of which were specially commissioned – that achieve the monumentality the space demands. At the entrance, Simone Leigh’s Brick House is a 16ft-tall bronze bust of a Black woman without eyes and a torso combining the forms of a skirt and a clay house (previously seen along New York City’s High Line). The Ghanaian sculptor Kwame Akoto-Bamfo’s bronze We Am Very Cold depicts several figures, including a child, contorted as if in a perpetual storm. David Tanych’s steel Free at Last is an 8ft-diameter ball with a giant chain and open shackle.

Kehinde Wiley’s An Archaeology of Silence stands 17.5ft high. Invoking the visual language of heroes and martyrs in European historical art, it depicts a shirtless man in jeans and sneakers draped limply over a regal horse, acknowledging the legacy of slavery in lynchings, police brutality and other violence against Black bodies – yet with a grace and vitality that hints at resurrection.

Brad Spencer’s From the Ground Up depicts a life-size man, woman and child made entirely of brick. An accompanying panel notes that the tiny fingerprints of enslaved children who turned bricks as they dried can be seen today on the bricks of historic buildings in Charleston, South Carolina. Visitors to the park can see and touch bricks made by enslaved people 175 years ago.

The park performs a further act of excavation. For more than three centuries enslavers often decided what enslaved people were called; the US Census recorded them only with a number. After the civil war, some 4 million newly freed Black people were able to formally record a surname in the 1870 census. All 122,000 of these surnames are inscribed on the National Monument to Freedom, a 43ft-tall, 150ft-long wall angled like an open book, its concrete clad with a bronze-gold metal facade that changes with the light.

Stevenson, 64, a public interest lawyer revered for his work on prison reform and death row, comments: “The enduring truth about enslaved people was their capacity to love, to find and create family and relationships that allowed them to survive and endure and overcome the brutality and I think that should be celebrated.

“There’s a narrative of triumph that we need to acknowledge and the monument is a gesture toward that, as a physical space but also as a way of naming names, making personal, making human this history. For people who are descendants to come and see that name and have a tangible connection made to that legacy is important and necessary.”

There is no more fitting venue for the park than Montgomery, capital of Alabama (a state that Donald Trump won by 35 percentage points in 2020) and crucible of American contradictions. It has witnessed one of the most conspicuous slave trading communities in the nation but also an act of courage by Rosa Parks that ignited the civil rights movement (a statue of Parks marks the spot where in 1955 she boarded the bus where she would refuse to give up her seat to a white man).

On a six-acre rise overlooking the city, Stevenson built a memorial – comprising 800 corten steel monuments – to more than 4,400 Black people killed in racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950. But this is also a city where the Alabama state capitol (built by enslaved brickmakers and bricklayers) still features a heroic monument to the Confederacy, the breakaway southern states that fought to preserve slavery, and a statue of Jefferson Davis, inaugurated here as its first president in 1861.

Inside there are still portraits of the Confederate general Robert E Lee and Governor George Wallace, who declared in 1963: “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Confederate banknotes are still displayed in the old treasurer’s office while eight murals inside the capitol dome still include “Secession and the Confederacy, Inauguration of President Jefferson Davis, 1861” and “Wealth and Leisure Produce the Golden Period of Antebellum Life in Alabama, 1840-1860”.

Last week, at the nearby First White House of the Confederacy , a tour guide could be heard enthusing to white tourists, “You’re on the Jefferson Davis trail!” as a Black woman entered wearing a T-shirt that said: “But still, like air, I’ll rise – Maya Angelou.”

Rarely is the American paradox felt so keenly. In the jarring juxtaposition of progressivism versus revanchism, of the beauty of Stevenson’s vision versus the mausoleums of white supremacy, how does he avoid a permanent sense of whiplash? “We’re in an era of transition,” he muses philosophically. “When I moved here in the 1980s, there were 59 markers and monuments to the Confederacy and you couldn’t find the word slave, slavery or enslavement anywhere in the city landscape.

“It was a part of a history that no one acknowledged, let alone discussed, and we are still under the cloud of a historical narrative that is false and unhealthy about the greatness of ‘the lost cause’ where we romanticise this effort to preserve slavery and to maintain white supremacy. That has to be challenged and we’re going to have to move from that and you’re slowly beginning to see that.”

Until this year, Stevenson notes, the three biggest high schools in Montgomery, with student populations that are 98% Black, were named after Confederates – but not any more. “There is some sobering around this effort to celebrate people who did horrific things, just like it would be unconscionable to go to Germany and see Adolf Hitler statues or monuments to the perpetrators of the Holocaust.

“We’ve got to reckon with the fact that we are glorifying people who were insurrectionist, tried to destroy this nation, represented a commitment to a racial order that was corrupt by this false idea that Black people are not as good as white people. With each year and each decade, we’re going to have to do more to get to a more honest space.

“That hasn’t happened in the way that it will need to happen in Alabama but it is happening . We are on that path and I don’t think that we can be a schizophrenic about history. History is history and we need to reckon with it and, when we reckon with it, we’ll find the courage to celebrate people – white people included – who did extraordinarily honourable things.”

Stevenson, author of the 2014 memoir Just Mercy , which became a 2019 film starring Michael B Jordan , likes to work on his historical projects covertly until they are ready to go public, thereby avoiding prejudgment by the unnerved, the resentful and the downright racist. You could call him a stealth truth bomber. The community then generally embraces his efforts, not least because they attract visitors who boost the local economy.

The Legacy Museum, which opened in 2018 and moved to a new, greatly expanded building on the site of a former cotton warehouse three years later, has few original artefacts but draws a compelling line from slavery to mass incarceration through narrative, interactive, newspaper excerpts, photos, statistics, videos, works of art and imagination. A haunting exhibit contains 800 jars of soil collected from lynching sites around the country as part of EJI’s Community Remembrance Project .

Now it is the turn of the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park to make the intangible tangible. Bricks. Names. Elms, oaks, sycamores, cottonwoods and chinaberries. A river and a railway. Love in the midst of agony. Speaking in Montgomery in 1965, Martin Luther King observed: “The climactic conflicts always were fought and won on Alabama soil.”

Stevenson observes: “The existence and the emergence of these truth-telling spaces allows us to say, look, if we can do this in Montgomery, Alabama, there’s not another place in America that can say, ‘They did that in Montgomery but we couldn’t possibly do it here.’ That’s the power of this place collectively because we are steeped in that long history of denial and resistance to ending slavery, to ending lynching, to ending segregation. We have an opportunity to be on the other side of this movement to commit to truth that will give us a unique credibility and power.”

The Freedom Monument Sculpture Park opens in Montgomery, Alabama, on 27 March

Most viewed

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury units constructed for entertainment enterprises, such as lake or harbour tour boats.

Riverboats are still a rich American tradition, and they truly were a formative part of American history. If you ever have the opportunity, schedule a cruise or even an afternoon tour on one of America's replica paddleboats. It's an experience that will take you back in time.