Yachting World

- Digital Edition

The foiling phenomenon – how sailing boats got up on foils to go ever-faster

- Matthew Sheahan

- July 20, 2015

The biggest revolution to hit watersports has been foiling, but how did it start and what are the issues involved? Matthew Sheahan investigates

Here’s a challenge. Design a way to support the weight of five saloon cars on a plate the size of your desk on the water. That was the task that faced America’s Cup designers in their bid to make the new breed of foiling America’s Cup boats fly.

If that’s a bit tough, here’s an alternative. Support a 70kg person and their boat in the water on a plank the size of a cricket bat. This one is much easier, the GCSE of hydrodynamics by comparison, with plenty of examples as to how it can be done thanks to the proliferation of foiling Moths around the world.

Getting boats to fly above the water surface is simple in theory, but tricky in practice and has challenged designers for over a century, but in the last decade one class appears to have cracked it.

On the face of it, International Moths on hydrofoils are sailing’s answer to the unicycle. But Moth sailors are far from being trick cyclists, there is a serious side to all this. A foiling Moth will reach 14 knots upwind and 20 knots downwind in just ten knots of wind, and in 20 knots of breeze they’ll be cranking along at 17 knots upwind and 25-30 knots down.

The International Moth has done more than any class to raise the profile of sailing hydrofoils. Photo: Thierry Martinez/Sea&Co

Whether you’ve seen the pictures or experienced the ghost-like whistle followed by the eerie vacuum that trails behind as they come slicing past, it is clear the Moth fleet has done much to publicise the thrill, grace and speed of sailing hydrofoils. The rapid growth of the class has also shown us that foiling is not just for pioneers and record breakers, but that despite several failed attempts in the past to bring it to the masses, this time there just might be a future in foiling.

Another reason why this particular class has exerted so much influence in sailing and spawned a new cycle of design is that Moths can race as a fleet round a course, foiling upwind and down. Although there are plenty of other boats that foil, most have a limited sailing repertoire and need specific conditions to fly. A Moth can fly on all points of sail and is capable of tacking and gybing too.

This has been one of the biggest steps forwards and has helped to boost recent interest from designers and sailors for other potential foiling projects.

Foiling, it’s a drag

At high speed, drag and seakeeping become big issues aboard any vessel, particularly offshore monohulls, and while yacht design has made some big steps forward since the days of hauling half the ocean behind in a pair of breaking quarter waves, there are other issues holding back performance.

Razor-straight wakes ironed flat by beamy after sections are clearly a step forward. Yet the problem for monohulls is that, as they slam and crash their way into the waves, keeping the structure in one piece is a big challenge. Rising above the water’s surface not only reduces drag, but might help to reduce structural risks and make handling at speed easier.

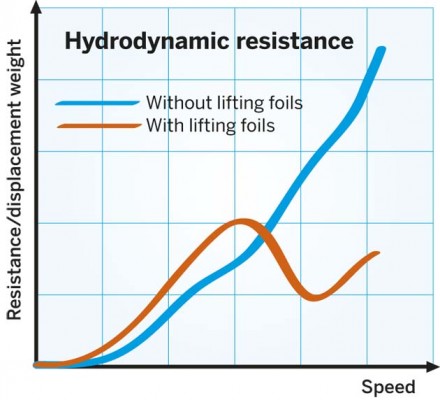

Typical resistance curve showing the rapid reduction in drag once a vessel gets airborne

Forty years ago it looked as though offshore foiling was about to make a breakthrough. David Keiper took the concept cruising in the 1970s with his trimaran Williwaw (see below), in which he clocked up a staggering 20,000 miles cruising the South Pacific. A decade later, French sailing legend Eric Tabarly broke the schooner Atlantic’s west to east transatlantic record set by Charlie Barr in his foiling trimaran Paul-Ricard.

Yet despite such feats, offshore foiling stalled. Tripping up at speed and keeping the boat in one piece when it touches back down have been the main concerns. And while neither of these two pioneers suffered such a fate, there are plenty of wince-inducing reminders of how it can all go pear-shaped.

But today foiling is more popular than ever. The French tri-foiler and former world record holder L’Hydroptère was the first sailing boat to break through the 50-knot barrier. Since then, a new world record has been set by Paul Larsen’s Sailrocket, another foiler, albeit an extreme one, which owes its success to a recent breakthrough in hydrodynamics.

L’Hydroptère, former speed record holder. Photo: Christophe Launay

Both share a longer-term view of taking foiling offshore. So does the British foiling cat project C-Fly with its canard configuration.

Meanwhile, the America’s Cup cats are trying to scorch around an inshore racecourse on foils that have no moving control surfaces. It’s a big ask of a high-speed boat and there have been spectacular crashes.

Then there’s SYZ&Co, the 35ft foiling cat on Lake Geneva, the new L’Hydroptère.ch, as well as the hull-less Mirabaud LX. These are just a few of the better known foiling projects, but plenty of others are experimenting with hydrofoils in subtler, more discreet ways – and not just racers and record-breakers.

Foils not just for the few

Cruising catamaran manufacturers Catana launched a 59ft luxury cruising cat that has curved daggerboards that the builders claim produce half a tonne of lift at ten knots. The Dynamic Stability System (DSS), which uses a hydrofoil in the horizontal plane, doesn’t aim to raise the boat out of the water, but instead uses hydrodynamic lift to improve its performance – although the new Quant 23, claimed to be the first foiling keelboat, uses the DSS is a new and thrilling way.

Quant 23, claimed to be the first foiling keelboat

And then there are those who seek to bring the thrills of hydrofoils to the average sailor. In quick succession there have been a couple of 36ft Infiniti multihulls, the Flying Phantom, the Gunboat foiling 40ft G4 and the Formula Whisper foiling catamaran, possibly the first foiler designed for club sailors. There has even been a first Foiling Week in July 2014, where a number of different foiling boats strutted their stuff.

Foiling is in vogue and capturing people’s imagination. But apart from the Moth sensation, why is foiling so popular now and where is this all leading?

Material advances

As is so often the case, the answer lies in the development of new materials and techniques. Weight and strength is at the heart of the issue and carbon has once again played a big part.

While foiling clearly appears to reduce the wave-making drag considerably, there is no free lunch. Lift and drag go hand in hand and what happens beneath the surface can sometimes wipe out any benefit above. For example, tilting a foil at a large angle of attack may create lift, but there will often be a large amount of drag too.

“You don’t fly for the beauty of it,” says aeronautical engineer Joseph Ozanne, Oracle’s lead wing designer for the two previous America’s Cup cycles. “People forget that to generate sufficient lift to raise an entire boat can mean introducing a lot of drag. Just because you’re flying doesn’t mean you’re suddenly more efficient or faster.”

Josephe Ozanne, who worked for Oracle duing the last two America’s Cups

To test this, put your hand horizontally outside a car window while it’s going along and rotate it gradually. Initially, with a small angle of attack, your hand will want to rise, but as you twist your palm further, the force pulling it backwards increases significantly.

It’s the same with foils; you can generate lift at high angles of attack, but you won’t necessarily be going any quicker simply because you’ve lifted out of the water.

30kg all up

As a generalisation, less weight means less vertical force is required, which means small angles of attack, which in turn means low drag. From here it’s easy to see how modern materials and the dramatic reduction in the all-up weight of modern boats has helped to make hydrofoils more feasible. Taken to extremes, a modern Moth weighs just 30kg all-up, less than half the weight of its crew.

But the theory doesn’t work for all lightweight, powerful boats; there is a limit.

“Back in 2006 when we were designing Mike Golding’s Gamesa, we looked into the possibility of a fully foiling Open 60,” reveals designer Merfyn Owen. “An Open 60 is a pretty powerful boat and when you compare the sail area:displacement ratio with that of a Moth there appears to be evidence that a foiling 60 could work.

“The trouble is that, unlike a dinghy where the crew generates huge righting moment when compared to the weight of the boat by sitting it out, on an Open 60 the rules on stability prevent you from generating enough righting moment to get the boat fully up on its foils. The Open 60 also has a wide draggy hull compared with a Moth with lots of wetted surface area that holds you back.”

So if an Open 60 would struggle to get up, the prospect for other large foiling monohull keelboats is looking doubtful.

SYZ&Co cants its daggerboards to vary the amount of side force and vertical lift

Multihulls, on the other hand, are lighter for the same length and sail area and can generate huge amounts of righting moment without putting on weight, thanks to their wide beam. This makes them better suited to hydrofoils. But there are other problems to overcome and several key configurations to consider.

Foiling configurations

The first issue is how much foil surface area you need to lift the boat. This varies with speed: the faster you go, the less you need. Early foil design used ladder-type racks of foils which lifted out of the water as the boat went faster, reducing the number of immersed foils as the speed increased. But this comes with a big drag penalty at slow speeds.

Surface-piercing configurations, where the foils are angled in a V shape, also find their own natural ride height depending on the speed. As the boat accelerates, the foils generate more lift, raising the boat, which in turn reduces the amount of foil in the water until equilibrium is achieved. The boat finds its own ride height automatically, with no moving parts required.

The configuration works in a similar manner with heel. As the boat heels to one side, more foil is immersed on the leeward side – and less to windward – which helps to right the boat. This inherent stability makes the surface-piercing configuration a popular one – it can be seen on boats like L’Hydroptère . But the problem comes at slow speeds when the high drag of the fully immersed foils hampers performance.

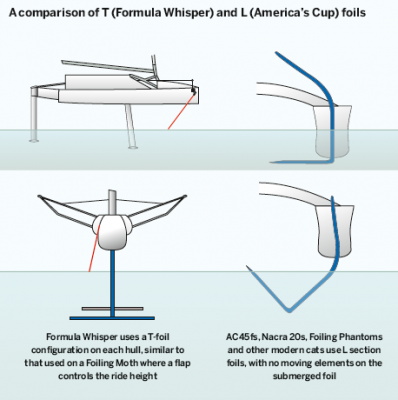

Fully submerged foils, where the lifting part of the arrangement is a horizontal foil mounted under the water at the bottom of a vertical strut, offer the lowest drag, but they have to incorporate an additional element to control the ride height. In other words, the foil has to change its lift characteristics depending on speed.

To do this, the horizontal foil has a moving element on its trailing edge like an aircraft’s elevator. In the case of the Moth, this elevator is connected mechanically to a ride height sensor, a wand that skims across the water’s surface. The lower the boat is travelling above the water, the more the elevator is deployed, creating more lift. But as the boat accelerates the lift increases and it starts to rise. The wand then takes up a different angle from the water’s surface and reduces the deflection of the elevator, reducing the lift.

Apart from the difficulty of following the sea’s surface in big waves, the problem for most sailing boats, especially keelboats, is that this configuration doesn’t provide any athwartships stability. The Moth stays upright because its crew hikes to windward. The same is true for other dinghies and cats that use crew weight for righting moment. On monohulls it’s difficult to make the configuration work.

‘C’, ‘L’ and ‘S’ foils

But not everyone wants to fly. In recent years there has been a great deal of development in foils with complex shapes from ‘C’ shapes, to ‘L’ and ‘S’ shapes and now ‘S’ foils with winglets. Generally speaking, these foils are less concerned with flying and more with the balance between generating sideways lift to drive you upwind and vertical lift to reduce displacement. Much of this development work took place in the former ORMA 60 multihulls.

“By canting the leeward daggerboard you can change the balance between lateral and vertical lift,” explains Vincent Lauriot-Prévost of designers VPLP, experts in high-performance multihulls and some of the world’s more extreme designs such as USA-17 and L’Hydroptère.

“When you’re sailing upwind, side force from the daggerboard is very important, as it is in any boat, but as you sail freer and faster you need less foil to create the required side force. Normally you would lift the board to reduce the drag, but if you leave it down and then cant it in towards the centreline, you create some vertical lift which then helps to reduce the displacement of the boat.

“Another way to achieve a similar effect is to have a curved daggerboard. A simple ‘C’ shape provides more vertical lift the further it is pushed down. The next stage of development was then to try ‘S’ shaped boards which, again, vary the distribution of lift and side force depending on where the boards are set.”

Although more expensive to build than straight boards, curved daggerboards have the advantage that they do not need complex canting mechanisms. Some classes and rules ban the latter so this is an alternative approach.

“Our ORMA 60 design Gitana II, which won the Route du Rhum in 2006, would see a reduction in displacement of 40 per cent at 20 knots,” says Lauriot Prévost. “At 26-28 knots the displacement would reduce to 70-75 per cent for a boat that weighs 6.5 tonnes fully loaded.”

This puts the issue of displacement reduction into perspective for cruising boats. Half a tonne of lift at ten knots from a curved daggerboard might sound a lot, but when the boat displaces 22 tonnes loaded, the displacement reduction is just over two per cent. While this may still have a beneficial effect on performance, it becomes easier to see that the future for cruising hydrofoils is not so clear cut.

Changes to trim, stability and displacement through subtle alterations in the alignment of foils is also a growing trend in the Open 60s and now the Volvo 65. Angling the keel pin up at its forward end by a few degrees provides a positive angle of attack on the keel fin when canted out to windward. When swung out to one side, the fin acts like an aircraft’s wing and helps to support the boat, although the lift also tends to reduce the effective righting moment.

Nevertheless, according to at least one top designer, the effort is worth it. He says: “There are some other performance details involved with this that I can’t speak about!”

Foils of the future

Where is the current craving for foils taking us? One of the biggest foiling experiments at present is in the America’s Cup. With their notoriously big budgets, Cup campaigns are well-known to accelerate the development of ideas that can eventually trickle down. What kind of technology breakthrough will wingmasted cats on foils provide?

The answer is not a simple one as the AC72s used in the 2013 Cup were never originally intended to foil. A loophole in the rule, exploited by the New Zealand team and deemed legal by the jury, sent teams off exploring the possibilities, but with little scope to control the foils themselves as no moving parts are allowed.

In the 2013 America’s Cup, the Kiwis exploited a loophole in the rule to put their catamaran on foils

“The Kiwis look good on foils, they are stable in pitch and heave and their foils appear to be reliable. But this will all come at a cost: drag,” said Oracle’s Joseph Ozanne at the time. “Less pitch stability, as our boats had, can reduce drag, but it makes the boat very tricky to sail. We did a lot of wheelies when we were learning to sail our boat. Regulating flight height is a nightmare.

“Modern aircraft are designed to be more unstable to improve manoeuvrability and also to reduce drag, but they have systems that keep them under control. We are not allowed these systems, so it’s the crew that have the control. So the key foiling lessons from the Cup could be learning about foil shapes and how to handle instability.”

For Sailrocket II’s foil designer Chris Hornzee-Jones, another aeronautical engineer, hydrofoiling means speed. Having set a new world record at 64.54 knots and broken into new territory, Hornzee-Jones believes this is just the beginning.

Chris Hornzee-Jones, Sailrocket’s foil designer

“I’m convinced we can get to 70-75 knots with subtle developments to this foil,” he declares. “Beyond that it becomes progressively harder, but the fact that powered craft on foils have achieved 80-100 knots confirms that there are foil shapes that will work at this speed. I think it may be difficult to get a single foil to perform over the entire speed range. We already use two on Sailrocket. Nevertheless, I do see over 80 knots as possible.”

The lessons learnt in this new speed territory could also have implications at far slower speeds and for much less extreme boats.

“Thick foils like the one we developed are good structurally,” says Hornzee-Jones. “Creating a foil that ventilates at low speeds means that at, say, 20 knots you are already into low drag.”

Like a gearbox and engine combination that allows you to engage top gear at 20mph and accelerate though to 100mph without changing gear, versatile, vice-less foils could indeed transform the behaviour of our boats in the future. Add to that the possibility of active control using sophisticated, compact and efficient electronics and new possibilities emerge.

Opening our minds

Although the average cruising monohull may not want to get up and flying, efficient low-drag stabiliser foils, for example, controlled by a tiny chip, could make the notoriously rolly tradewind conditions on a transatlantic a more comfortable and efficient affair.

Vincent Lauriot-Prévost

“Foiling Moths have opened people’s minds,” says Vincent Lauriot-Prévost. “The future will depend on having good control of efficient foils. We will need to change camber profiles effectively and develop automatic trim regulation. But, we must also think weight, otherwise the systems won’t work.”

Perhaps it is no surprise that after more than 70 years of sailing development at the leading edge of the sport, many are still scratching their heads at how to make such a promising concept work for the rest of us.

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams. Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

Hydrofoils for Sailboats

- By By Steven Callahan

- Updated: July 29, 2020

Hydrofoils have been providing dynamic lift since fish sprouted fins. And people have been employing foils ever since they first put paddle to water, and certainly since adding keels and rudders to boats. But the modern, flying America’s Cup boats, kiteboards, Moth dinghies, shorthanded offshore thoroughbreds—these are all playing in a new world in which the terms “hydrofoils” or “lifting foils” describe those oriented to raise a hull or hulls from the water. In these racing realms, if you ain’t got foils, you ain’t got nothin’.

Lifting foils that allow these boats to sometimes home in on three times the wind speed might appear to be of little interest to cruising sailors, but with such common cruising features as self-steering and autopilots, self-tailing winches, rope clutches, fin keels and faster hull shapes all having been passed down from the racing scene, one must ask, “What promise, if any, do hydrofoils hold?”

Lifted or partially lifted boat patents extend back to 1869, but workable watercraft took roots along with early flight. Italian Enrico Forlanini began experimenting with foils in 1898. In 1906, his 1-ton 60 hp foiler reached 42.5 mph. Alexander Graham Bell’s HD-4 Hydrodrome flew on Bras d’ Or Lake at 70 mph in 1919. And several sailing foiler patents began appearing in the 1950s. Notably, JG Baker’s 26-foot monohull, Monitor, flew at 30-plus mph in 1955. Baker experimented with a number of foil configurations, and at least built, if not used, the first wing mast. The first offshore foiler was likely David Keiper’s flying trimaran, Williwaw , in which he crisscrossed the Pacific in the 1960s.

By the 1980s, numerous speed-trial and foil-enhanced offshore-racing multihulls showed huge promise, and have since evolved into behemoth trimarans clocking 30 to 40 knots continuously for long periods, not to mention the monohulls in the Vendée Globe (and soon the Ocean Race) that are capable of speeds exceeding 30 knots. But as boat designer Rodger Martin once reminded me, “If you want a new idea, look in an old book.” He was right. The fully foiling monohulls that will compete in the 2021 America’s Cup will bring things back full circle to the foiling monohull Monitor .

Fluid Dynamics Primer

Any foil—a wing, sail, keel, rudder or lifting foil—redirects the flow of fluid (air included), creating high- and low-pressure areas on opposite sides of the appendage, while developing lift perpendicular to the foil’s surface.

Advancements in foiling science is due in part to the hundreds of foil shapes that were tested, with tabulated results, by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the forerunner of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. For the better part of a century now, aircraft and boat designers have been able to choose from a spectrum of refined foil sections that produce predictable amounts of lift and drag for known speeds of fluid and angles of attack, or the angle at which the foil passes through the fluid. Sections of efficient faster foils, as seen on jets or as we flatten our sails to go upwind or reach high speeds, have smaller nose radii and are thinner, with the thickest section of the foils farther aft, up to nearly halfway toward the trailing edge.

The most efficient foil sections at slow speeds are fatter, with the maximum thickness farther forward, and with larger nose radii, than faster foils. The angle to fluid flow or angle of attack also is greater. We see these slower foils on wings of prop planes and sails when off the wind or in light conditions.

Most sailors are familiar with traditional foils on boats, the teardrop sections of keels that produce lift to weather, reducing leeway, and of rudders, allowing them to steer. Even a flat plate can be a foil, but these tend to be inefficient. Such a shape is prone to fluid separation from the surface, meaning they stall easily, and they maintain poor lift-to-drag ratios. Even keels and rudders are somewhat lift-compromised because they are symmetrical and have to work with fluid coming from either side, whereas lifting foils are more like aircraft wings or propellers, with asymmetrical sections honed for performance in a more stable, fluid flow.

The point is, any foil can be employed at various angles to the surface to prevent leeway, produce increased stability, or help lift the boat out of the water. But those not required to work with fluid flowing from opposite sides can then be honed to maximize lift and minimize drag. Asymmetrical foils were used on boats like Bruce King’s bilgeboarders, including Hawkeye , back in the 1970s. And, designers, including Olin Stephens, had previously employed trim tabs behind keels to improve keel performance.

Sails, which are heeled airfoils, not only drive the boat forward, but they also produce downforce, actually increasing the dynamic displacement of the boat. To counter this and keep the boat sailing more upright, multihull designer Dick Newick first employed slanted asymmetrical hydrofoils in the outer hulls of his small charter trimaran, Lark , in 1962. A portion of the lift developed by the hydrofoil resisted leeway, while a portion worked to actually lift the leeward hull, keeping the boat more upright and reducing dynamic displacement and drag.

Anyone who has ridden on even a foil-stabilized boat will know how riding at least lightly on the waves, and especially above them, beats smashing through them. When boats lift off, everything gets a lot smoother, drag falls away, and the boat accelerates.

Cruising on Foils

But why would a cruiser want to whip over the sea? Wouldn’t this demand an inordinate amount of attention by the crew? Would lifting foils even be applicable to a boat that must have substantial displacement to carry crew and stores? Aren’t cruising-boat hydrofoils an oxymoron?

Maybe, but I believe our boats’ hulls are likely to sprout fins much as fish have as we orient foils to more efficiently resist leeway, add stability, aid steering, reduce drag, increase comfort, allow for shallower draft, and enhance wider variations in hull shapes.

Boats have gotten increasingly wide through the years to advance form stability, improve performance (primarily off the wind), and boost interior volume. But the downside is that fat boats tend to slam more upwind. What if you could reduce dynamic displacement of the boat and lift that hull even partially from the water? The result would be less slamming, especially upwind.

At the same time, what about narrower boats that are known for being more seakindly, especially when closehauled, but lack form stability to carry adequate sail area for powering upwind, and tend to roll badly downwind? Or shallow-draft vessels that are lovely for cruising, but again, tend to suffer from reduced stability? Foils can give that stability back.

Looking ahead, boat designers might choose to reduce ballast, making up for it with a foil. In short, lifting foils can reduce boat drag and motion while increasing power and performance.

Pitching also does no favors for speed or crew comfort. Foils can come into play here as well. Foils parallel to the sea’s surface resist motion up and down, and a lifted boat skating above chop also is less prone to hobby-horsing through waves. Multihulls have always been particularly susceptible to pitching for a number of reasons, but watching videos of multihulls sailing to weather show an obvious huge advantage that foilers have compared with nonfoilers. Offshore multihulls now routinely employ T-foils on the rudders to control the fore and aft angles of the boat (attitude), a feature easily adaptable to any vessel.

OK, so what’s the cost? Obviously, the more things sticking through the hull, especially if they are retractable, the more it’s going to impact the interior. There would be added weight, complexity and cost. Foils also create noise, and there’s susceptibility to damage from hitting stuff. And let’s not forget compromises with shapes, purposes and things not yet imagined.

As for damage, it’s possible to fold the foils back into the hull. Think swinging center- boards or actual fish fins. Daggerboardlike foils can at least employ shock-absorbing systems similar to the daggerboard arrangements found in many multihulls. This includes weak links that are outside the hull, so if a foil is struck, it frees the foil to fold back or to come off before being destroyed or damaging the hull. Or, foils might hang from the deck rather than penetrating the hull, allowing them to kick up (and to be retrofitted to existing boats). These configurations also relieve the interior of intrusions, and keep the noise more removed from it. I have no doubt that numerous talented designers will be exploring all kinds of options and compromises in coming years, finding ways to make foils both practical and more than worth the compromises.

Sailing more upright, shallower draft, speed, comfort—what’s not to like? Just what is possible? I have a feeling the cruising community is about to find out.

Steven Callahan is a multihull aficionado, boat designer and the author of Adrift , an account of his 76 days spent in a life raft across the Atlantic.

- More: foils , How To , hydrofoils , print june july 2020 , sailboat design

- More How To

How to Rig Everything in Your Favor

Is There a Doctor Aboard?

3 Clutch Sails For Peak Performance

It’s Time to Rethink Your Ditch Kit

Cruising the Northwest Passage

Balance 442 “Lasai” Set to Debut

A Legendary Sail

10 Best Sailing Movies of All Time

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

SuperFoiler Grand Prix is the ‘F1’ of hydrofoil sail-racing. There is no other entertainment product like it in the world.

The SuperFoiler is a highly advanced, purpose-built machine that drives unrivalled performance.

The world’s best sailors agree that our IP and ambition exemplify leadership in the new combined dimension that is flying and sailing.

Our aim is to deliver dynamic racing, create rich content as well as develop new on and off- water experiences.

"The difficulty, the speed, the trapeze, these challenges draw the world's best sailors. The SuperFoiler Grand Prix is not for the faint hearted!"

With a crew of three, communication and courage will be the key to these machines.

About the Teams

SuperFoiler brings together aerodynamics and hydrodynamic excellence to create the fastest foil-borne machine of its size on the planet.

About SuperFoiler

We're social

Connect and engage with us to keep up to date!

- --> YouTube

Our Partners Find out more

- Motorcycles

- Car of the Month

- Destinations

- Men’s Fashion

- Watch Collector

- Art & Collectibles

- Vacation Homes

- Celebrity Homes

- New Construction

- Home Design

- Electronics

- Fine Dining

- Baja Bay Club

- Costa Palmas

- Fairmont Doha

- Four Seasons Private Residences Dominican Republic at Tropicalia

- Reynolds Lake Oconee

- Scott Dunn Travel

- Wilson Audio

- 672 Wine Club

- Sports & Leisure

- Health & Wellness

- Best of the Best

- The Ultimate Gift Guide

Boat of the Week: Meet the ‘Patriot,’ the New Lightning-Fast America’s Cup Foiling Yacht Representing the US

After being airlifted 9,000 miles from the factory, the 45-foot sailing racer exceeded designers' initial expectations by zigzagging around the auckland waterfront at insane speeds., michael verdon, michael verdon's most recent stories.

- Taking a Bow: How Yacht Makers Are Rethinking the Rear End

- Airliners Are Trying Radical New Wing Designs to Improve Fuel-Efficiency

This New 262-Foot Superyacht Lets You Mix and Match 3 Interior and Exterior Designs

- Share This Article

Patriot , the just-launched America’s Cup racing yacht representing the United States, completed its first week of sailing last week in New Zealand . The New York Yacht Club’s representative team, American Magic, tested the potential of a design that had only been proven by computer simulation. The 75-foot navy-hulled Patriot , which just days before had been shipped by cargo plane 9,000 miles from Rhode Island, streaked across the Auckland waterfront, zigzagging on its foils, videos suggesting it reached its “sound barrier,” or top speed, of an estimated 50 knots (America’s Cup teams don’t like to talk about top speeds), or 57 mph.

Related Stories

Architects and fashion designers are penning yachts, and it’s changing how they’re made.

“We went off the dock thinking that if the breeze filled in, we’d have a good sail,” Terry Hutchinson, skipper and executive director of American Magic, said after the sail. “Straight away, we came into 21 knots [of wind pressure], and we were into it. Despite having a brand-new boat that we were all excited about, the whole session felt normal. That’s a great validation of our shore team and all of the work put in since we launched the Mule in 2018.”

“The Mule” was the first prototype that American Magic built to train its crew on at its facility in Pensacola, Florida, and that basic design was followed by Defender , a more complex boat that has been decommissioned since Patriot ’s arrival. Like its competitors Lunna Rossa from Italy, Britannia from the UK and the America’s Cup defender, Te Aihe from New Zealand, American Magic won’t divulge technical details about Patriot , beyond the fact its steering station is more forward than on Defender .

Patriot performed her first week of tests in front of the Auckland waterfront recently, as her team learns the idiosyncrasies of the lightning-fast foiling yacht, and designers figure out how to tweak for maximum speed. Courtesy Will Ricketson

The 75-footer is clearly fast, even out of the box, and for the next three months, designers and specialists will tweak the carbon-fiber hull and 1560-square-foot mainsail to make it even faster.

The world’s foremost sailing event, the America’s Cup has been around since 1851, though the last three Cups were more like Formula One racing, compared to the stately, slow-sailing monohulls of previous generations. The last three Cups have all been designed around foils, starting in 2013 with the AC72, and then three years ago, the boats became smaller, and much more nimble, 50-ft. catamarans that not only accelerated like an F-22 Raptor, but could nearly pivot on their own axis.

The last-generation cats were a bit too wild, so the powers that be came up with the current AC-72 class using a one-design rule where all competitors had to use common parts. The idea was to level the playing field. Organizers supply some parts of the boat, including the mast, rigging, foil-cant arms and hydraulics. The boats—16 feet wide with a crew of 11—are also built of lightweight composites because they’re designed to fly, rather than plough through the water.

While America’s Cup teams do not release top speeds, it’s estimated that the AC75 boats break the Cup’s “sound barrier” at about 50 knots, or 57 mph. Courtesy Will Ricketson

Patriot ’s foil-cant arms are also designed to move both under or outside the boat to provide the leverage to keep it upright. If it does capsize, the crews can right the boat much easier than the previous generations of foiling racers. Another new evolution for this America’s Cup is the twin-skin mainsail on the 87-foot-tall mast. The double-sail skins combine with the spar to generate the power the AC75 needs to foil. On the last two generations, the sails were much stiffer sail-wings that many non-Cup racers complained about because there was no trickle-down technology for the rest of the sailing world.

Beneath the water, Patriot also has an interesting breakthrough design. The foil-cant system uses new technology that employs a battery-driven, hydraulic-power unit to raise and lower the strong, but very heavy, foil-cant arms, that give the boat its stability and speed. As the boat changes tacks, the cant system is activated, placing one hydrofoil in the water, and lifting the other one out, where its weight becomes ballast.

Beyond the sail plan and hull design, the foil wings at the end of the arms will be another of Patriot ’s secret weapons. American Magic designers will have the ability to create any design they believe will be most effective to give the boat an edge over competitors, and the next month will be devoted to trying new shapes and sizes.

Patriot was built in Bristol, Rhode Island, by a 50-strong team and then shipped by cargo plane 9,000 miles to Auckland. Courtesy Will Ricketson

Considering the America’s Cup’s ambitious timetable, and the unexpected time pressures Covid-19 put on design and production of Patriot in Rhode Island, it’s amazing that this yacht came through so well. “This team didn’t exist three years ago, and now we have three boats built and two AC75s launched,” said Marcelino Botin, American Magic’s lead designer. “The first thing we need to focus on next is to make sure the new boat is sailed the way we want it to be sailed.”

Botin said this initial “analysis” phase will be critical to future modifications to the design. “We are all interested in knowing how the boat performs compared to our predictions and compared to our previous boat,” he says.

Hutchinson says that Patriot ’s initial performance was encouraging, especially on its first gybe. “We had a great nosedive, and that was exciting,” he said. “It was nothing that we haven’t seen or done on our other boats, and our familiarity with Patriot will increase rapidly over the coming days.”

The powerful foils allow Patriot to tack and jibe at high speeds, and to self-right if it capsizes. Courtesy Will Ricketson

Helmsman Dean Barker described the boat’s performance as “lively.”

After the America’s Cup World Series and Christmas Cup from December 17 to December 20 will come the Prada Cup Challenger Selection Series, from January 15 through February 22, 2021, where Patriot will compete against Luna Rossa and Britannia II for the challenger title. The winner of that event will then compete against Emirates New Zealand for the America’s Cup, which runs from March 6 through 15, 2021.

Read More On:

- America’s Cup

- New Zealand

- Sailing Yacht

More Marine

Rossinavi Just Launched a Custom, Full-Aluminum 164-Foot Superyacht

Meet Spear, an Epic 460-Foot Trimaran Concept That Looks Like It’s From the Year 3000

Culinary Masters 2024

MAY 17 - 19 Join us for extraordinary meals from the nation’s brightest culinary minds.

Give the Gift of Luxury

Latest Galleries in Marine

8 Fascinating Facts About ‘Nero,’ a 295-Foot Superyacht Inspired by a 1930s Classic

Palm Beach Vitruvius in Photos

More from our brands, first lady jill biden sparkles in sequined sergio hudson top and wide-leg pants at human rights campaign dinner, arizona’s sweet 16 run a bright spot amid $30m budget shortfall, ‘ghostbusters: frozen empire’ leads box office with $45 million debut, joan jonas, a performance art pioneer, gets the super-size moma retrospective she deserves, the best yoga blocks to support any practice, according to instructors.

Published on June 2nd, 2017 | by Assoc Editor

Foiling and Foil Shapes, a Beginner’s Guide

Published on June 2nd, 2017 by Assoc Editor -->

by Mark Chisnell, Land Rover BAR The rules covering the design and construction of the team’s America’s Cup Class (ACC) boat have defined many of the parts of the boat, including the hull and crossbeams (together called the platform), and the wing shape and size. What’s left for the team’s designers and engineers to work on is principally the daggerboards and rudders, and the control systems that operate them along with the wingsail.

A lot of the technology that goes into the control systems is hidden well inside the hull, with just glimpses of the HMI (human machine interface) that the sailors use to control the board rake, wing trim and so on. The foils are on full view however, so we thought a beginners guide to ACC foil design would come in useful now the racing is approaching.

Basic Principles The foils use exactly the same scientific principles as an aircraft wing. Just as an aircraft wing will lift a plane up off the ground, the foils of an America’s Cup Class boat will lift it out of the water. Wings are foils too, called aerofoils because they work in air. The foils on the new America’s Cup boats are more accurately called hydrofoils, because they work in water.

The secret to both types of foil is the shape – aerofoils and hydrofoils use a special shape to guide the wind or water around them, and generate the lifting force to get planes and boats up in the air. Of course, the America’s Cup boats also use an aerofoil. The main wingsail works exactly the same way as an aircraft wing, it’s just rotated to stand up straight, rather than lie flat.

While an aircraft needs an engine to push the air over the wing fast enough to generate enough force to lift the aircraft up off the ground, the wingsail on the Cup boat generates force from the wind blowing past it. The harder the wind blows, the more force it makes to push the boat forward. When the boat is going fast enough, the hydrofoils will then be able to create enough force to lift the boat out of the water. This reduces resistance to the forward motion and the boat goes faster still.

There are four hydrofoils on the boat — we count the rudders at the back because they have small wings at the tips called elevators. However, the real power to keep the boat in the air comes from the hydrofoils (the daggerboards, as you will often hear them called by the sailors) and we will concentrate on these.

The L-Foil The L-foil is exactly that; a vertical daggerboard shaft that goes through the hull of the boat, with a single horizontal hydrofoil on the bottom, the whole thing shaped like an ‘L’. If nothing else changes, then the L-foil keeps generating lift as the boat goes faster and so the boat keeps rising, and as it rises, less and less of the daggerboard is in the water.

At the basic level, two things then happen: firstly, the boat starts to slip sideways because there is less of the vertical part of the daggerboard in the water and this makes the boat feel unstable and hard to steer. Then, ultimately, if the boat keeps rising the horizontal part of the board that is doing all the lifting will break the surface. If it does, there will be a catastrophic loss of lift and the boat will come crashing back down.

Aircraft use moving parts on the foils to control the amount of lift – trailing edge flaps — but the rules forbid these on the ACC boats, so to maintain stable flight the sailors change the rake or angle of attack of the whole dagger board (and hence the foil) to the water.

Rake If you rake the board backwards as the boat accelerates, the lift will reduce and the boat will come to an equilibrium at a steady height above the water. This is all well and good until the conditions change, maybe the wind speed goes up or down, or the boat hits some waves. When that happens the rake will need further adjustment to find the new equilibrium… until the next puff or lull when it must change again.

In the big breeze and rough water of San Francisco Bay in the 34th America’s Cup it turned out that these moments of equilibrium didn’t last very long and on occasions barely existed at all. The crew’s ability to generate the hydraulic power to change the board and wing trim was simply overwhelmed; they couldn’t achieve stable flight.

V-foil The solution was what’s called the V-foil, in which the horizontal part of the ‘L’ is angled upwards to form more of a ‘V’ shape (the angle at the bottom of the ‘V’ is called the dihedral – a dihedral of 90 degrees would define an L-foil, less than that is progressively more of a V-foil).

The V-foil uses the same principle as one of the most successful original foiling powerboats. The grand old man of 19th century innovation, Alexander Graham Bell put a couple of 350hp engines on the back of what was called HD-4 and set a new marine world speed record in 1919 of just over 70mph.

HD-4 used three ‘ladders’ of small foils, one at the front, and one each side close to the back. When the boat accelerated it started to lift out of the water, and as it lifted, one by one the ‘rungs’ of the foils would break clear of the water. As they did so the lift would decrease, and unless the boat continued to accelerate the boat would stop rising and settle at an equilibrium.

The V-foil achieves this same effect with a single foil and is used in the commercial application of fast ferries— one runs between Southampton and Cowes on the Isle of Wight, right across the Solent waters where the team train, and has done so (on and off) since 1969 – so V-foils are well understood.

When a boat equipped with a V-foil keeps rising as more lift is generated by faster speeds, both parts of the ‘V’ come out of the water together. Critically, when the ‘horizontal’ section starts to break the surface at the tip, it has the effect of reducing the lift gradually, because it doesn’t all come out of the water together. So the boat comes back down gently, working towards an equilibrium ‘ride height’ of its own accord.

It might be that it doesn’t reach this equilibrium before something else changes, but the V-foil has some inherent stability (unlike the L-foil) that doesn’t require human intervention. The shape provides a feedback mechanism to control the amount of lift and produce a more stable ride at a consistent height above the water. The downside of the V-foil is that it will generate less lift and more drag than the L-foil under the same conditions, because some of the lift generated is pushing sideways rather than up.

So one of the big questions facing the teams at the outset of this campaign was whether or not the sailors could achieve stable flight with an L-foil in the new boats and the new venue. Bermuda was a very different place to San Francisco; the winds were expected to be lighter, the water flatter and it seemed that stable flight should be easier to achieve with an L-foil under human control.

A huge amount of work has gone into foil and control system design and we now know that the answer is yes, they can – all the teams are using L-foils, often with unloaded dihedral angles of greater than 90 degrees. These angles close as the boat sails and the foil is loaded up to become much closer to, or 90 degrees.

Cant Another buzz word for the 35th America’s Cup is the cant. The cant of the board is similar to the rake, except that the bottom of the board is moving sideways across the boat, to and from the centreline, rather than backwards and forwards. When the board is canted outwards (towards the edge of the boat) it creates greater ‘righting moment’ and more power to drive the boat forwards.

Righting Moment When the wind hits a sail it creates the force to move the boat forward but it also creates a force that is trying to tip the boat over. If you have ever seen a dinghy or yacht knocked flat by a big gust of wind then you’ve already got the idea.

It’s considerably simplified, but essentially the more force that can be applied to resist the wind’s effort to tip the boat over, then the faster the boat will go, because more of the wind’s energy can be captured and applied to forward motion. The resisting force is called the righting moment and creating as much righting moment as possible is a fundamental principle of designing fast sailboats. It’s the reason that you see people leaning over the windward side when they are racing, putting bodies as far out on the windward side as possible is creating righting moment.

S-Foil Finally, there’s the question of whether the vertical part of the daggerboard should be straight or ‘S’ shaped. The curve of the S-foil could be used — like the cant — to move the bottom of the board outboard and increase the righting moment. So S-foils are more powerful, but they are also more difficult to use. The curves have to raised up and down through the bearings and internal mechanisms in the hull, and that means a lot of work to keep the friction down and the efficiency high.

Tags: AC35 , America's Cup , foiling , Land Rover BAR , Mark Chisnell

Related Posts

Hydraulics: Key to the Cup? →

The Last Days of the Schooner America →

America’s Cup: Half the crew will pedal →

Italy and the America’s Cup →

© 2024 Scuttlebutt Sailing News. Inbox Communications, Inc. All Rights Reserved. made by VSSL Agency .

- Privacy Statement

- Advertise With Us

Get Your Sailing News Fix!

Your download by email.

- Your Name...

- Your Email... *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Subscribe Now

- Digital Editions

Foiling technology: everything you need to know about hydrofoils

Fitting foils to powerboats is all the rage, but how do they work and why is foiling back in fashion?

What is foiling?

Foiling refers to the use of hydrofoils attached to the hull of fast boats, which provides additional lift at planing speeds – often enough to lift the hull completely clear of the water.

What is the benefit of this?

Efficiency. The enemy of fast boats is the amount of effort required to push them through the water. Planing boats go some way to addressing this by rising up over their own bow wave and skimming across the surface, but the stern sections are still immersed, creating significant hydrodynamic drag. It follows that if you can lift the boat completely clear of the water, hydrodynamic drag is only acting on the foils themselves and the sterngear that propels and steers it.

Any advantages beyond efficiency?

Lifting the boat clear of the surface can reduce the disturbance of waves, smoothing the ride, but only up to a point. It’s not just about lift though – active foils can also be used to improve stability or handling and in some circumstances, can improve efficiency even without lifting the boat.

Recommended videos for you

How do foils work.

Foils work in a similar way to aircraft wings. In simple terms, as they move through the water they deflect the flow, which exerts a force on the foil. If that force is upward, the faster they move, the greater the lift.

So why are they so much smaller than aircraft wings?

Because water is much denser than air – almost 800 times, in fact. The foils have far more to push against than aircraft wings, so don’t require the same surface area.

Is this new technology?

Far from it. Foiling technology can be traced back to 1898 when Italian inventor Enrico Forlanini began work on a ‘ladder’ foil system, obtaining patents in both the UK and the USA. He had a prototype operating on Lake Maggiore soon after. British boat designer John Thornycroft followed up with a series of scale models featuring stepped hulls and a single foil, and by 1909 had a full-scale 22ft prototype running. During WWII, the German military developed a 17-tonne foiling mine layer that was tested in the Baltic at speeds of up to 47 knots. By the early 1950s, the first commercial hydrofoil ferry was running between Italy and Switzerland and a decade later, a private hydrofoil yacht featured in the Bond movie Thunderball.

Why did they never catch on in production boating?

Traditionally, high-speed hydrofoils used large V-shaped foils that jutted out beyond the boat’s beam. This made berthing tricky and increased the draught. They were also costly to construct, vulnerable to damage and difficult to power, as the propellers of conventional shaftdrives would be clear of the water once foiling. Lastly, although hydrofoils were often more efficient than monohulls, high-speed cats could usually match the efficiency without the drawbacks.

Why are they back in the news?

Foiling technology came back into public focus when the 2013 America’s Cup contenders started to use foil-shaped daggerboards to hit speeds of more than 40 knots. Ben Ainslie’s spectacular last-gasp victory for the Oracle USA team and his subsequent BAR Land Rover Cup Challenger brought foiling to a global audience. More recently, we’ve seen the emergence of several foiling motor boats, including the SEAir RIB and the Sunreef Open 40 Power. More exciting still is the news that Princess will use an advanced Active Foil System on its new R Class superboat .

What has changed?

Technology has overcome many of the shortfalls of older systems. Simon Schofield, chief technology officer at BAR Technologies, told MBY the real game changer has been the adoption of ‘Dalí’ foils. Instead of two fixed V-shape foils, Dalí foils use four independent L-shaped blades that stick out of the hull at an angle before curving up like Salvador Dalí’s famous moustache. They are far more efficient and can be retracted, solving the berthing and draught issues. In addition, computer-controlled active systems allow the foils to be adjusted to suit speed and sea conditions. This doesn’t just improve efficiency, it can enhance the ride and handling too. When cornering, for example, a traditional hydrofoil boat doesn’t lean into the turn, making it uncomfortable for passengers. An active system can adjust each foil to induce the correct degree of lean. Modern materials also reduce drag and cavitation.

How about propulsion?

The Enata Foiler uses twin BMW diesel 320hp engines, but instead of being connected to the propellers with hefty drag-inducing shafts and gearboxes, these generate electric power which can be sent down a thin flexible cable to slender electric motors mounted on the retractable rear foils.

Lifecord – The kill cord revolution

Lifecord, a new alarmed smart kill cord that knows when you are not wearing it, ensures you’ll never forget to

Motor boat stabilisers: DMS’s new stabilisation fins

DMS's new flapping fins could become a staple for motor boats

Hybrid heaven: Adler’s 76 Suprema

Taking diesel electric propulsion to a new level, Adler's 76 Suprema may just be too innovative for the yachting marketplace

The world’s biggest electric foiling boat is coming

Sliver bullet first look – 130ft foiling boat with spaceship looks, toy of the month: pelagion hydroblade is the foiling tricycle of the future, latest videos, fairline targa tour: sensational new british sportscruiser, navan s30 & c30 tour: exceptional new axopar rival, galeon 440 fly sea trial: you won’t believe how much they’ve packed in, parker sorrento yacht tour: 50-knot cruiser with a killer aft cabin.

Support our hydrofoil educational content for free when you purchase through links on our site. Learn more

[2023] Hydrofoil Catamaran: The Ultimate Guide to Foiling on Water

- November 1, 2023

- Hydrofoil Basics

Experience the thrill of flying above the water with a hydrofoil catamaran!

Are you ready to take your hydrofoil boarding to the next level? Look no further than the hydrofoil catamaran. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll dive deep into the world of hydrofoil catamarans, exploring their history, how they work, their benefits and drawbacks, and everything else you need to know to make an informed decision. So, buckle up and get ready to soar above the waves!

Table of Contents

Quick answer, quick tips and facts, how does a hydrofoil catamaran work, benefits of hydrofoil catamarans, drawbacks of hydrofoil catamarans, choosing the right hydrofoil catamaran, maintenance and care, recommended links, reference links.

A hydrofoil catamaran is a type of watercraft that combines the stability of a catamaran with the lift and speed of hydrofoils. It uses specially designed foils to lift the hulls out of the water, reducing drag and allowing for faster and smoother sailing. Hydrofoil catamarans are popular among sailors and water sports enthusiasts for their incredible speed, maneuverability, and thrilling foiling experience.

Shopping Links: Hydrofoil Catamarans on Amazon | Hydrofoil Catamarans on Walmart | Hydrofoil Catamarans on Etsy

- Hydrofoil catamarans can reach speeds of up to 40 knots (46 mph) or more, depending on the design and conditions.

- The foils on a hydrofoil catamaran can lift the hulls out of the water, reducing drag and allowing for a smoother and faster ride.

- Hydrofoil catamarans are used for various purposes, including racing, recreational sailing, and even transportation.

- Foiling on a hydrofoil catamaran requires some skill and practice, but it’s an exhilarating experience once you get the hang of it.

- Hydrofoil catamarans come in different sizes and designs, catering to different skill levels and preferences.

Hydrofoil catamarans have a fascinating history that dates back to the early 20th century. The concept of using hydrofoils to lift boats out of the water and reduce drag was first explored by Italian engineer Enrico Forlanini in the late 1800s. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that hydrofoil technology started to gain traction in the boating world.

The first hydrofoil catamaran, known as the “Aquavion,” was developed by the French engineer René Guilbaud in the 1950s. This innovative design combined the stability of a catamaran with the lift of hydrofoils, revolutionizing the world of sailing. Since then, hydrofoil catamarans have evolved and become more advanced, offering incredible speed, maneuverability, and stability on the water.

A hydrofoil catamaran works by utilizing hydrofoils, which are wing-like structures mounted underneath the hulls of the boat. These foils generate lift as the boat gains speed, lifting the hulls out of the water and reducing drag. This lift allows the hydrofoil catamaran to achieve higher speeds and a smoother ride compared to traditional boats.

The hydrofoils on a catamaran are typically designed with a curved shape, similar to an airplane wing. This shape creates a pressure difference between the upper and lower surfaces of the foil, generating lift. The foils are usually adjustable, allowing the sailor to fine-tune the performance of the catamaran based on the sailing conditions.

To control the hydrofoil catamaran, sailors use a combination of steering and sail trim. By adjusting the angle of the foils and the sails, they can optimize the lift and balance of the boat, ensuring a stable and efficient ride. It takes some practice to master the art of foiling on a hydrofoil catamaran, but the rewards are well worth the effort.

Hydrofoil catamarans offer a range of benefits that make them a popular choice among sailors and water sports enthusiasts. Here are some of the key advantages of hydrofoil catamarans:

Speed : Hydrofoil catamarans are known for their incredible speed. By lifting the hulls out of the water, hydrofoils reduce drag and allow the boat to glide smoothly above the waves. This enables hydrofoil catamarans to reach impressive speeds, making them a thrilling choice for racing and high-performance sailing.

Maneuverability : The lift generated by hydrofoils enhances the maneuverability of catamarans. With reduced drag, hydrofoil catamarans can make sharp turns and quick maneuvers with ease. This agility is particularly useful in racing scenarios, where every second counts.

Stability : The dual-hull design of catamarans provides inherent stability, even at high speeds. When combined with hydrofoils, the stability of hydrofoil catamarans is further enhanced. This stability makes them suitable for sailors of all skill levels, from beginners to experienced professionals.

Efficiency : Hydrofoil catamarans are more efficient than traditional boats. By reducing drag, hydrofoils allow the boat to sail faster while using less power. This increased efficiency translates to longer sailing distances and reduced fuel consumption, making hydrofoil catamarans an environmentally friendly choice.

Versatility : Hydrofoil catamarans are versatile watercraft that can be used for various purposes. Whether you’re looking for a high-performance racing catamaran or a recreational sailboat for family outings, there’s a hydrofoil catamaran to suit your needs. Some models even offer the option to switch between foiling and non-foiling modes, providing flexibility on the water.

While hydrofoil catamarans offer numerous benefits, it’s important to consider their drawbacks as well. Here are a few potential downsides to keep in mind:

Cost : Hydrofoil catamarans tend to be more expensive than traditional boats. The advanced technology and materials used in their construction contribute to the higher price tag. Additionally, maintenance and repairs can also be costly, especially if specialized parts or services are required.

Learning Curve : Foiling on a hydrofoil catamaran requires some skill and practice. It can take time to learn how to control the boat effectively and maintain stability while flying above the water. Beginners may find the learning curve steep, but with dedication and proper instruction, anyone can master the art of hydrofoil catamaran sailing.

Weather Conditions : Hydrofoil catamarans are sensitive to weather conditions. While they excel in flat water and moderate winds, rough seas and strong gusts can pose challenges. It’s important to be aware of the weather forecast and choose suitable sailing conditions to ensure a safe and enjoyable experience.

Transportation and Storage : Hydrofoil catamarans can be larger and bulkier than traditional boats, making transportation and storage more challenging. Specialized trailers or racks may be required to transport the catamaran, and adequate storage space is needed to protect it when not in use.

Despite these drawbacks, the thrill and excitement of foiling on a hydrofoil catamaran outweigh the challenges for many sailing enthusiasts.

When it comes to choosing the right hydrofoil catamaran, there are several factors to consider. Here are some key points to keep in mind:

Skill Level : Consider your skill level and experience as a sailor. Some hydrofoil catamarans are designed for advanced sailors, while others are more beginner-friendly. Choose a catamaran that matches your skill level to ensure a safe and enjoyable sailing experience.

Intended Use : Determine how you plan to use the hydrofoil catamaran. Are you looking for a racing catamaran, a recreational sailboat, or something in between? Different models offer varying features and performance characteristics, so it’s essential to choose a catamaran that aligns with your intended use.

Budget : Set a budget for your hydrofoil catamaran purchase. Prices can vary significantly depending on the brand, model, and features. Consider both the upfront cost and the long-term maintenance expenses when determining your budget.

Brand and Reputation : Research different brands and their reputation in the hydrofoil catamaran industry. Look for brands with a track record of producing high-quality, reliable catamarans. Reading customer reviews and seeking recommendations from experienced sailors can also provide valuable insights.

Demo and Test Sails : Whenever possible, try out different hydrofoil catamarans before making a final decision. Many manufacturers and dealers offer demo and test sails, allowing you to experience the performance and handling of the catamaran firsthand. This hands-on experience can help you make an informed choice.

Remember, choosing the right hydrofoil catamaran is a personal decision that depends on your individual preferences and needs. Take your time, do your research, and consult with experts to find the perfect catamaran for your hydrofoil adventures.

Proper maintenance and care are essential to keep your hydrofoil catamaran in top shape and ensure its longevity. Here are some maintenance tips to help you keep your catamaran performing at its best:

Rinse with Fresh Water : After each sailing session, rinse your hydrofoil catamaran with fresh water to remove salt and debris. Pay special attention to the foils, as saltwater can cause corrosion over time.

Inspect for Damage : Regularly inspect your catamaran for any signs of damage or wear. Check the foils, hulls, rigging, and sails for any cracks, dents, or loose fittings. Address any issues promptly to prevent further damage.

Store Properly : When not in use, store your hydrofoil catamaran in a dry and secure location. If possible, keep it covered to protect it from the elements. Consider using a boat cover or storing it in a boat shed or garage.

Follow Manufacturer’s Guidelines : Follow the manufacturer’s guidelines for maintenance and care. Each catamaran may have specific recommendations for cleaning, lubrication, and other maintenance tasks. Adhering to these guidelines will help prolong the life of your catamaran.

Seek Professional Assistance : If you’re unsure about any maintenance tasks or need assistance, don’t hesitate to seek professional help. Local boatyards, sailing clubs, or authorized dealers can provide expert advice and services to keep your catamaran in optimal condition.

By following these maintenance tips and caring for your hydrofoil catamaran, you can enjoy many years of thrilling foiling adventures on the water.

How fast is the hydrofoil catamaran?

Hydrofoil catamarans can reach impressive speeds, depending on various factors such as the design, wind conditions, and skill of the sailor. Some high-performance hydrofoil catamarans can exceed 40 knots (46 mph) or more. However, the exact speed will vary based on these factors.

How does a foil catamaran work?

A foil catamaran, also known as a hydrofoil catamaran, works by utilizing hydrofoils to lift the hulls out of the water. These foils generate lift as the boat gains speed, reducing drag and allowing for faster and smoother sailing. The lift created by the foils enables the catamaran to “fly” above the water, resulting in increased speed and improved performance.

What happened to hydrofoils?

Hydrofoils have a rich history and have been used in various applications, including passenger ferries, military vessels, and recreational boats. While hydrofoils experienced a surge in popularity in the mid-20th century, their use declined in some sectors due to factors such as high costs, maintenance challenges, and the development of alternative technologies. However, hydrofoils continue to be used in niche markets, including high-performance sailing and racing.

Read more about “… What is the World’s Largest Hydrofoil Boat?”

Are hydrofoil boats more efficient?

Yes, hydrofoil boats are generally more efficient than traditional boats. By lifting the hulls out of the water, hydrofoils reduce drag and allow the boat to sail faster while using less power. This increased efficiency translates to longer sailing distances and reduced fuel consumption. However, it’s important to note that the efficiency gains may vary depending on factors such as the design, sailing conditions, and skill of the sailor.

Hydrofoil catamarans offer an exhilarating and thrilling experience on the water. With their incredible speed, maneuverability, and stability, they have become a favorite among sailors and water sports enthusiasts. While they may come with a higher price tag and require some skill to master, the rewards of foiling on a hydrofoil catamaran are well worth it.

When choosing a hydrofoil catamaran, consider factors such as your skill level, intended use, budget, and the reputation of the brand. Take the time to research and test different models to find the perfect catamaran for your needs.

So, are you ready to take flight on a hydrofoil catamaran? Embrace the thrill, experience the freedom, and enjoy the incredible sensation of soaring above the water. Happy foiling!

- Hydrofoil History

- Advanced Hydrofoiling Techniques

- Hydrofoil Equipment Reviews

- Why do boats not use hydrofoils?

- iFLY15 – iFLY Razzor Pro – Foiling Catamaran

- Hydrofoil Catamarans on Amazon

- Hydrofoil Catamarans on Walmart

- Hydrofoil Catamarans on Etsy

Review Team

The Popular Brands Review Team is a collective of seasoned professionals boasting an extensive and varied portfolio in the field of product evaluation. Composed of experts with specialties across a myriad of industries, the team’s collective experience spans across numerous decades, allowing them a unique depth and breadth of understanding when it comes to reviewing different brands and products.

Leaders in their respective fields, the team's expertise ranges from technology and electronics to fashion, luxury goods, outdoor and sports equipment, and even food and beverages. Their years of dedication and acute understanding of their sectors have given them an uncanny ability to discern the most subtle nuances of product design, functionality, and overall quality.

Related Posts

Can you put a hydrofoil on any board [2024] 🏄♂️.

- March 13, 2024

Is Hydrofoil Harder Than Surfing? [2024] 🏄♂️

- March 3, 2024

Are Hydrofoil Boards Hard to Ride? [2024] 🏄♂️

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Add Comment *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Trending now

Live updates: New Zealand Sail Grand Prix at Lyttelton, Christchurch

Newshub's Mitch Redman gets a guided tour of NZ SailGP boat Amokura. Credits: Image - Photosport, video - AM

Click here to refresh page

4:43pm - And that's the end of the day's racing, before it even begins. The racing window has closed and Mother Nature has carried the honours.

Surely tomorrow, we'll be better prepared... such a shame for the record paying crowd, who go home without seeing any racing.

Join us again at 3pm Sunday for live updates of the revised racing scheduled.

4:33pm - Still no racing, due to "mammals on course", which is a little embarrassing. The same thing happened last year and dolphins are quite common in this area, so it wouldn't have takent much foresight to make sure they had something to do somewhere else today.

The opening race has been delayed, after a dolphin was sighted on the course. SailGP is known for its respect for the ocean and nature, so wellbeing of wildlife comes before racing.

2:57pm - Great Britain have been docked points - both from the NZ regatta and the season standings - after a training incident with Spain.

The Brits collided with the Spanish boat during the third practice race on Friday and the penalty may have ended their chances of reaching the series final at San Francisco.

"We’re licking wounds from that issue," said GBR driver Giles Scott. "It's really, really frustrating, but tomorrow's a new day - we'll come out swinging and see what the weekend's got."

The British now sit seventh overall, 11 points out of the top-three cutoff for the final.

Kia ora, good afternoon and welcome to Newshub's live coverage of NZ Sail Grand Prix at Christchurch's picturesque Lyttelton Harbour.

Last year saw the international sailing circuit visit the South Island for the first time and many of the participants described the stopover as the best of the year.

This event was scheduled for Auckland, but unavailability of suitable venues forced organisers to return to Lyttelton, which isn't a bad back-up option.

More from Newshub

The home team were pipped by Kiwi skipper Phil Robertson and his Canadian crew in 2023, but the newly branded 'Black Foils' are determined to take honours this weekend, after back-to-back success at Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

Driver Peter Burling wans't at the wheel for the last regatta at Sydney, while he was on babywatch, so he'll chase a hattrick of victories at Christchurch.

Saturday's racing will consist of three fleet races, while Sunday will see two more, plus the three-boat final.

The fleet and championship standings are:

Australia - Tom Slingsby

New Zealand - Peter Burling

Denmark - Nicholai Sehested

Spain - Diego Botin

France - Quentin Delapierre

Great Britain - Giles Scott

United States - Taylor Canfield

Canada - Phil Robertson

Germany - Erik Heil

Switzerland - Nathan Outteridge

Join us at 3pm for the first race.

TAB Odds: Australia $2.90, New Zealand $3.25, Denmark $8, France $11, Spain $11

Canada's Kiwi skipper out to spoil homecoming party again at SailGP Christchurch

The black boat isn't the only one chasing a 'home' win at the New Zealand round of SailGP this weekend.

Last year, Kiwi Phil Robertson stole the show, when he drove his Canadian team to victory on Lyttelton Harbour.

Robertson is back in the country for the first time since the famous win and his sights set on a repeat effort this weekend, but defending his title isn't the only reason to come home.

"It's pretty hard to compete with New Zealand coffee around the world," Robertson told Newshub.

As it turns out, that rule applies to most beverages - including the alcoholic variety.

"I definitely like the local craft breweries and get into it... but I still love a Speights," he joked.

Come Sunday, he'll hope those beers will be celebratory. Last year, he helped Canada achieve their only event win to date, spoiling the party for local hero Peter Burling and the NZ boat.

"That was up there," he reflected. "That was massive."

Not everything about being home is bright and sunny.

"It's cold here, but the colder air brings a denser air, so you go faster," he noted.

The ever-comical Robertson has his own way of describing windy conditions at the last event in Sydney.

"You've got to bring your brown undies and buckle up, because it's going to be a wild ride," he said.

Robertson confirms those brown undies have been included in his luggage this weekend.

"I packed my brown undies, but hopefully I won't need them, because I love the speed."

That should be music to the ears of a record 22,0000 spectators who will make this weekend the world's largest ever ticketed sailing event.

"An event like this here in Christchurch, I'm really hoping it inspires the local kids down here to get into it, because it's a wicked sport and there's so many opportunities around the world," he said.

If Robertson can go back-to-back for Canada, there would be no better example set.

Shamrock Shuffle 2024: More than 26K participants kick off Chicago's outdoor running season

CHICAGO (WLS) -- It is considered a rite of spring in Chicago.

The Shamrock Shuffle is back on Sunday morning.

ABC7 Chicago is now streaming 24/7. Click here to watch

Runners from across the Midwest and throughout the country are in Chicago for the scenic run through the city that has been kicking off the outdoor running season for more than four decades.

"It's a great launch to running in Chicago," said Shamrock Shuffle Executive Director Carey Pinkowski. "It's getting people moving. We have the whole celebration of St. Patrick's Day, and now, we're moving to a little bit more healthy and active from the parades and all the stuff we do."

The 8K run snakes through downtown started at 8:25 a.m.

SEE ALSO | Full list of street closures for 43rd Annual Bank of America Shamrock Shuffle

More than 26,000 runners from Illinois to California to New York descended on Grant Park on Sunday morning, showing how popular the Shamrock Shuffle is.

"This is really the kickoff to the running racing season, so it's great to be out here, great vibe. My favorite part is being able to do this with my daughter," said Brookfield's Zack Fijal.

It is a Chicago tradition that Zack hopes to continue with his daughter, Abby Fijal.

"I like seeing all the buildings and stuff, and all the people cheering is really fun," Abby said.

Others, like 11-year-old Tristan O'Meara, took on the Shamrock Shuffle for the very first time.

"The race went really well for me. It's my first time doing a five mile and I'm really proud of getting this medal," Tristan said. "I felt just amazed, and with my mom and dad and aunt cheering me on, it just gave me so much joy."

There was also a 2-mile walk along the Lakefront Trail and a 1-mile run.

Related Topics

- COMMUNITY & EVENTS

- DISTANCE RUNNING

- ROAD CLOSURE

M.E.A.N. Girls Empowerment to highlight health disparities at summit

- 2 hours ago

Tribute dinner to honor contributions of refugee, immigrant women

Yachtapalooza, 1-day Chicago boat show, 'perfect for aspiring sailors'

Full list of street closures for 2024 Shamrock Shuffle

Top stories.

Timeline of allegations against former Fenton HS staffer released

1 dead, off-duty officer among 5 wounded in Indiana shooting: police

Mail carrier robbed on nw side: officials.

CPD releases video of suspects in North Side armed robbery spree

1 dead, 2 critically injured after south suburban crash: CFD

California chiropractor chases down suspect after alleged sex assault

California mountain lion attack leaves man dead, injures his brother

- 3 hours ago

Trump's Truth Social completes merger that could net him over $3B

When is the Boat Race 2024? Start time, TV channel and how to watch as Cambridge battle Oxford

The Boat Race returns in 2024 with Cambridge and Oxford again battling it out on the River Thames.

The men’s race was first held 195 years ago and has been an annual event since 1856, with a women’s race running on the same day and course since 2015.

There was double joy for Cambridge last year as both their male and female crew bested their Oxford University rivals over the 4.2-mile weave through London.

Indeed, Cambridge crews completed a clean sweep of all races in 2023, with their openweights, reserves and lightweights also taking victory in a feat only achieved twice before.

Here’s everything you need to know.

When is the Boat Race?

The 2024 Boat Race will take place on Saturday 30 March along the River Thames in London.

How can I watch it?

Viewers in the United Kingdom can watch live on BBC One, with coverage on the channel from 2pm GMT. A livestream will be available via the iPlayer.

If you’re travelling abroad and want to watch major sporting events, you might need a VPN to unblock your streaming app. Our VPN round-up is here to help and includes deals on VPNs in the market. Viewers using a VPN need to make sure that they comply with any local regulations where they are, and also with the terms of their service provider.

What is the course?